Africans saving Africa

In one part of Ethiopia, communities are putting the world’s governments and many aid agencies to shame.

|

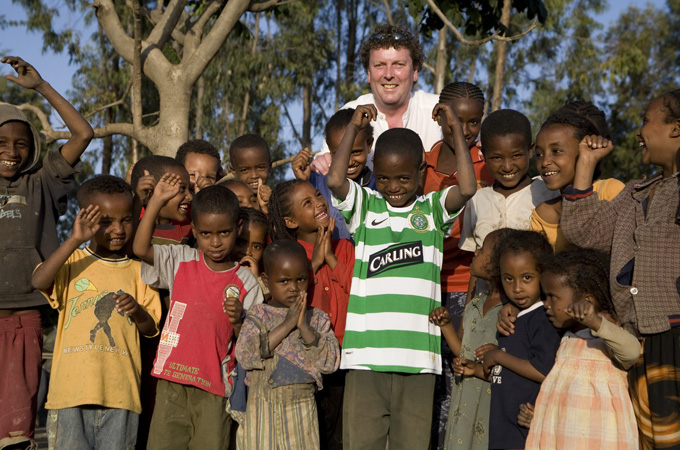

The following was posted in the blog of award-winning filmmaker, Jamie Doran, back in July 2007 following his first shoot in Ethiopia.

“When we arrived in Sodo region, around 120 kilometres south of Addis Ababa, my first and lasting impression was the pride in their faces,” says Doran. “This was a region that had been devastated by drought and famine on many occasions in the past and I had expected a nervous, even frightened population as rumours abounded at the time of a new drought. Instead, I found a community confident in itself, certain of its ability to survive by its own means.”

Just a week later, on the flight home, it was clear he had caught the bug. Within a matter of months, he would return to Ethiopia to begin a film that would take almost two years to complete with a cast of thousands. Although he does not say it in the following blog, the affect the people of Sodo had upon him will last a lifetime and he still remains in touch with those involved in the project.

Just returned from Ethiopia after a visit which should put the world’s governments and many aid agencies to shame.

The general perception of Ethiopia, gained through grim television pictures and the odd article in some glossy magazine whose editor has discovered a social conscience for about 20 seconds, is of famine-stricken, dried up, dust-covered desperation. This was my first visit to the country and, frankly, I had roughly the same perception before my arrival. What I discovered opened my eyes up not just to how much needs to be done, but how it is being done by Africans themselves.

|

| As part of the project 20 people were taught new skills which they then had to pass on to 20 others |

We all remember Band Aid and Live Aid (or those of us of a certain age do) and how 1.5 billion of us united through the medium of TV to combat the terrible famine which had struck the country back in 1984, highlighted by Michael Buerk’s extraordinary reports. Rock stars in their hundreds battling with each other to board the bandwagon (sorry) of hope was a sight to behold. After donating our 50 quid or whatever – particularly after that incredibly moving video showing starving Ethiopian kids to the tune of Drive by The Cars – we thought we’d done our bit for Africa. The total raised eventually reached around £150mn or around $300mn at today’s exchange rates. [Just thinking; 1.5 billion raised $300mn – not a lot, but still more than the six cents per American head which actually reach Africa each year from the US. I digress.]

Bandwagon is an unfortunate pun in more ways than one. Much of the money raised through the efforts of those rock stars was directed towards buying second-hand trucks to distribute aid etc. The donkey who came up with that idea should have visited Ethiopia just six months or so later to see how many of his purchases had broken down, never to see a road again. Here was the perfect example of Westerners telling Africans what they needed, rather than thinking things through and, most importantly, asking the Africans what was really required.

This brings me back to my recent trip. If you drive around Ethiopia, the real tragedy of well-intended yet misguided aid efforts is there for everyone to see. Abandoned health centres, recently-built schools collapsing through neglect, soil dried to dust in areas of plentiful rainwater. It doesn’t seem to make sense; that is, until you realise that most of these aid-backed projects were attempted in isolation: one NGO here, another there, thinking they know best what is needed now, rather than looking to the long term.

Ethiopia is a poor country, with most of its population living in what is termed ‘extreme poverty’ (accepted definition: less than $1 per day). But Ethiopia should not be a poor country; large areas are lush green with plenty of opportunity for cultivation. The key is to direct aid in such a way that it avoids sporadic development and, instead, achieves long-term success through integrating all of the requirements a community needs to thrive. In other words, what’s the point of building a school when the kids are too hungry, or sick with malaria, to attend? You need to provide them with food, health care and education at the same time. This is only part of it, but you get the idea.

The fancy phrase is ‘holistic development’ and it’s not pie-in-the-sky wishful thinking; I saw it with my own eyes during my visit: large swathes of land being irrigated to produce cash crops which, in turn, could be sold at market (the tradition had been to grow maize, more maize and more still); schools being built, new health centres, savings and lending schemes allowing investment in rudimentary tools which revolutionise production and, crucially, food storage to ensure that if the rains do not arrive one year there’s enough food to feed their families. In short, a major success story run entirely by Ethiopians themselves.

A group called Self Help Africa runs the project in the Sodo region I visited, along with others in various parts of the country. To see such immense pride on the faces of the farmers planting their new crops, on the children walking to their new schools and, particularly, on the women who run the savings and lending schemes is a memory which simply doesn’t fade. Whole communities coming together, hundreds of men, women and children digging ditches, building dams: millions of gallons of rainwater which had previously crashed off the mountainside, dragging topsoil from the land below until eventually pouring uselessly into the river and being lost forever, now being stopped in its tracks. That rainwater now seeps into the ground, raising the water table.

In one vast area, the water table stood at 300 metres below the surface just 18 months ago; virtually impossible to access. Today it’s at 80 metres and, within a year, will sit at just eight metres down – easily accessible using the simplest and cheapest of water pumps.

You can probably tell that I was knocked out by what I saw. For me, the message is simple: If you give aid directly to those who know intimately the problems of their own country, it’s going to be used properly – no rocket science required.

Africa Rising can be seen from Wednesday, August 10, at the following times GMT: Wednesday: 2000; Thursday: 1200; Friday: 0100; Saturday: 0600; Sunday: 2000; Monday: 1200; Tuesday: 0100; Wednesday: 0600. Click here for more on Witness. |