Transcript: Norman Finkelstein

The full transcript of our discussion on whether the two-state solution can solve the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Read the full transcript of Head to Head – Time to boycott Israel? below:

Part one

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Mama we’re dying’: Only able to hear her kids in Gaza in their final days

Europe pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

Birth, death, escape: Three women’s struggle through Sudan’s war

Mehdi Hasan (VO): With every peace talk,Israel has cemented its occupation. Crushing dreams of peace and Palestinian statehood. My guest tonight, however, thinks old maps can still create new borders. But is he stuck in the past?

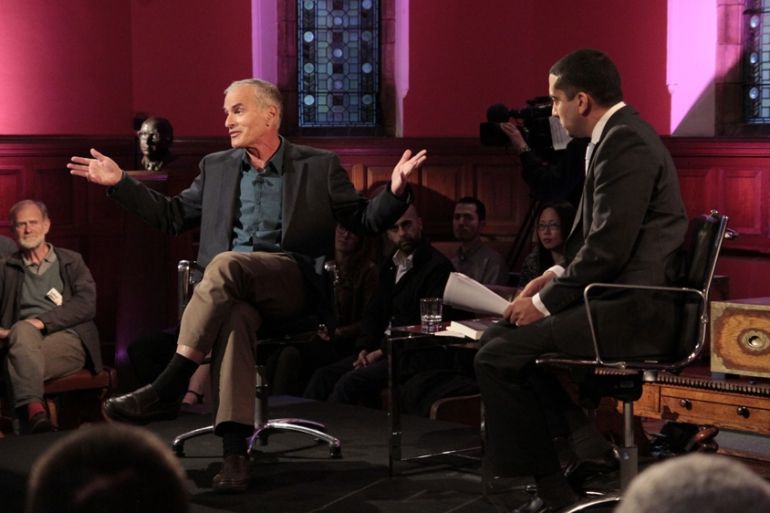

I’m Mehdi Hasan and I’ve come here to the Oxford Union to go Head to Head with controversial author and academic Norman Finkelstein. He’s been called a self-hating Jew by some supporters of Israel, and having once been a rock star of the pro-Palestinian movement, he’s now attacked by many for his refusal to back a boycott of Israel. Today, I’ll challenge him on how he can still believe a two-state solution is possible, and why he’s dismissed the boycott movement as a “cult”.

I’ll also be joined by Salma Karmi-Ayyoub, a leading Palestinian activist and human rights lawyer in London. Jeff Halper, the Director of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions in Jerusalem. And Oliver Kamm, a columnist for The Times of London and The Jewish Chronicle.

Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Norman Finkelstein.

Mehdi Hasan (VO): A controversial figure, he’s the author of several books including The Holocaust Industry and How to Solve the Israel-Palestine Conflict.

Mehdi Hasan: Thank you for coming here. Norman, your new book is called How to Solve the Israel-Palestine Conflict. Given the US Secretary of State John Kerry is the latest person to have tried and failed to do so, what makes you think that you have the solution to this conflict?

Norman Finkelstein: Well, first of all, Secretary of State Kerry did not try to solve the Israel-Palestine conflict in a way that’s reasonable for both sides. He’s basically, or has been basically, trying to impose the Israeli position on the Palestinians. My own view is there is a reasonable possibility for solving the conflict. There’s enough international support for it, there’s enough popular support for it, and now the key is for the Palestinians themselves to mobilise in favour of that international consensus.

Mehdi Hasan: Which is?

Norman Finkelstein: Basically, it’s what it’s been for the past 30 years; it’s two states on the June 67 border and what’s called a just resolution of the refugee question.

Mehdi Hasan: The Palestinians, as you well know, better than me, first said that they would back a two-state solution back in 1988. Since then, over the last quarter of a century, we’ve had the Madrid Conference, the Oslo Accords, the Wye River Memorandum, the Camp David Summit, the Taba Summit, the Road Map, the Annapolis Conference, and lately, the John Kerry plan. None of them managed to bring about a two-state solution, and yet, you say that’s the most likely option. In what fantasy world is this two-state solution ever going to happen?

Norman Finkelstein: There’s a huge reservoir of support for the Palestinians, and the reservoir has now extended. It includes, for example, I think, large segments of the American Jewish community, which has grown disaffected from the state of Israel, and there are real possibilities of reaching American Jews as well.

Mehdi Hasan: Let me read to you what Professor Rashid Khalidi of Columbia University, one of the world’s leading Palestinian intellectuals, he says the two-state solution is now, quote, “Wizard of Oz stuff” and that people on the pro-Palestinian side, like yourself, who still cling to a two-state solution, he says, quote, “need to have their heads examined”.

Norman Finkelstein: Well, if that were the case, then you’d have to say there’s no possibility for any reasonable resolution of the conflict because if the two-state settlement is supported by the international community, if that is “Wizard of Oz stuff” then one-state is “Man on the Moon stuff”. So you have two possibilities right now: there is the two states, as has been embraced by the international community, and then there’s the, what you might call at this point, the Kerry initiative, namely, imposing Israel’s bottom line to Palestinians. One state is not part of the debate.

Mehdi Hasan: Many people would argue that the two-state solution, yes, you can vote on it every year in the UN Assembly, you can win over American Jewish support, but the reality is that the facts on the ground have rendered it impossible, unviable, there are now too many Israeli settlements, too many Jewish settlers, too many Palestinians, all stuck living together in the West Bank, in East Jerusalem, and it’s too late to disentangle, it’s too late to unscramble the omelette.

Norman Finkelstein: The Palestinians, during what were called the Annapolis negotiations in May 2008, they did present which were, what were, I would say, were very reasonable maps. They presented the map, for example, which showed Israel can keep 60 percent of the settlers in place, 60 percent of the settlers in place in two percent of, two percent of the West Bank. And the Palestinian state would remain contiguous, it would remain a-a-a-a viable state. So…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] So you genuinely believe that half a million heavily subsidised, heavily armed Israeli settlers, many of them religious fanatics, will just leave without a peep to bring about this two-state solution?

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] No, absolutely not, they won’t leave without a peep. And there you have to know the details. Look, Tzipi Livni, who was then the Foreign Minister, she was in charge of negotiations. She didn’t deny it was a reasonable map. She said, “It’s not that your map is physically impossible,” she said it was “politically impossible”. That is to say, no Israeli Prime Minister could support such a map and still remain in office. The problem is not one of physics; the problem is one of politics.

Mehdi Hasan: Well, let’s go to our panel, who are sitting and listening to you speak. Jeff Halper is the Founder and Director of the Israeli Committee against House Demolitions in Jerusalem. Jeff, when Norman says it is reversible, it’s not irreversible, what’s your view on that, as someone on the ground wh-who faces these issues every day?

Jeff Halper: Well, we’ve said for a long time, um, that it’s irreversible, in my view, um, what’s happening on the West Bank, and that’s why we think the two-state solution has gone. It’s…it is reversible, it’s true, I agree with Norman, logistically. You know, there’s only a half… You can look at it this way, there’s only half a million settlers in the occupied territories. It’s possible to move them. What’s missing is the will to do that. And that’s the problem. If there was a concerted will on the part of Europe and the United States to say to Israel, “Look, it’s over. You go back to the 67 borders, period,” it’s doable. That’s true. But that will is absolutely missing.

Mehdi Hasan: Ok. Let’s bring in Oliver Kamm, who is a columnist and leader writer for The Times of London and for The Jewish Chronicle. Uh, Oliver, you’ve had your differences, I know, with Norman Finkelstein in the past, but on this, am I right in saying that you agree with him, that a two-state solution is still possible and the most likely outcome?

Oliver Kamm: I think it’s possible and I certainly, um, believe it is, overwhelmingly the most desirable outcome. Any other outcome is extremely, destructive. The problem is that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not merely a disagreement over borders. It is, and I do agree with, Norman Finkelstein on this, it is about politics, rather than, uh, rather than the physics of it. Um, the problem is that there have been proposals for a two-state settlement, 2000, 2008, nothing has come of them, and the two-state solution, on which there is a large international consensus, something approximating the pre-1967 armistice lines, um, is now being deferred again because of politics within both sides.

Mehdi Hasan: And a US official told an Israeli newspaper a few months ago that the Kerry plan fell apart, quote, “the primary sabotage came from the settlements,” he says.

Oliver Kamm: Yes I, I’m not going to defend the settlements, but I don’t think that the settlements, uh, per se, are an obstacle to a two-state solution. One can perfectly well see with land swaps, whereby 80 percent of the settlers, remain in place, um, that there’s a, um, that there’s the possibility of a two-state solution satisfying the national aspirations of both parties.

Mehdi Hasan: And do you think 80 percent of the settlers should be allowed to stay, under your vision of a solution?

Norman Finkelstein: Well, again, you keep personalising it and saying my vision of a solution.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Well, y-y-y-you’ve co-authored a book called How to Solve the Israel-Palestine Conflict.

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] …I said that…I said that…I said…right, but… The proposals that were made by the Palestinians in Annapolis in 2008, they said about 60 percent of the settlers can remain in place. It will change a little because now there are more settlers.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] More than half.

Norman Finkelstein: Yeah. About 60 percent will stay in place, but then there are other possibilities, and you have to keep them in mind. You mentioned correctly, a large number of settlers there are being subsidised. And then you have to ask the question: what happens if the Israeli government ceases its subsidies? And then you have the fanatics, and that’s true. And they asked one Israeli former security chief, “Well, what do you do about the fanatics?” He says, “It’s very simple, all you have to do is tell those crazy settlers in Hebron: if you want to stay, stay. But we’re leaving,” meaning the army is leaving…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] But that’s never going to happen, Norman.

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] And they’re… and you’re leaving 400 settlers…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] This comes back to Wizard of Oz stuff; it’s never going to happen.

Norman Finkelstein: No…

Mehdi Hasan: The Israeli army is never going to abandon settlers.

Norman Finkelstein: Well I don’t know why…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] And leave them…

Norman Finkelstein: …why you make that assumption. At the present moment, that’s correct…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Fifty years of history.

Norman Finkelstein: At the present moment, that’s correct because not very much pressure has been exerted on Israel. Israel has the first cost-free occupation in the history of humanity.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Ok.

Norman Finkelstein: The Palestinians do the dirty work, the Europeans pay the bills and Isr… and the United States blocks for them in the UN. So why should they leave?

Mehdi Hasan: Ok, well, let’s bring in…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] There’s no incentive to leave.

Mehdi Hasan: Let’s bring in Salma Karmi, who’s a Palestinian lawyer and activist. Uh, what’s your view? Are you someone who still wants to have that independent Palestinian state that so many Palestinians have said they wanted?

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub: I think the one thing that we’re overlooking in this whole discussion about the logistics of whether the two-state solution is practical or possible is whether it’s actually desirable from the Palestinian point of view. I think the problem that people need to bear in mind is that the Palestinian problem that needs a solution isn’t confined to those Palestinians living under occupation in the West Bank and Gaza. So, we need a solution that achieves rights for the Palestinian diaspora, for the refugees, and for those who are discriminated against in Israel. And the two-state solution patently doesn’t do that. It’s unfair because it only awards the Palestinians 20 percent of their historic homeland, and it doesn’t actually address the wider issues which afflict the Palestinian population. So it’s, it’s not right in principle, and it’s not workable.

Norman Finkelstein: What you want to look at is, in the broad public, in the international arena, what’s the furthest you can go? And the furthest you can go, in my opinion, for now, is what you might call enlightened public opinion. And enlightened public opinion, in the current world, is mostly the language of international law, the language of human rights. So you look at the most representative organisations in the world today and you look at what are their terms for resolving the conflict? They say two states.

Mehdi Hasan: Here’s what I don’t get with you, Norman

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Mmm hmm.

Mehdi Hasan: You’re someone who called Israel a “lunatic state”.

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Yeah.

Mehdi Hasan: You called President Obama a “stupefying narcissist, devoid of any principles, every bit as wretched as his predecessors.”

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Mmm hmm.

Mehdi Hasan: You call the Palestinian Authority “a gang of corrupt, wretched collaborators.” And, yet, your solution to the conflict involves those corrupt collaborators doing a deal with that lunatic state under the supervision of a wretched, narcissist president. [LAUGHTER] How does that work?

Norman Finkelstein: Hey… [APPLAUSE]

Norman Finkelstein: I’m not so sure, those of you who are clapping, what would you have done during World War II? I’m no great fan of Winston Churchill – I think he was a monster, in many ways. And what would you do with Mr Stalin? But then you want to defeat the Nazis, and there was an alliance between Mr Churchill and Mr Stalin to defeat the Nazis. So, what are you gonna do? You gonna reject them both? Then, fine, then you’ll have a Nazi ruling the world. You have to bring to bear pressure on the US government. I think there are real possibilities now. Israel’s stock has dropped precipitously in the United States, not just broadly, but even in the American Jewish community.

Mehdi Hasan: Norman, do you not see the contradiction, then, in their thinking, in your thinking? Because a few moments ago, you told us, you’ve told previous interviewers that “I work with the limits of public opinion”. And, yet, you’re telling us that, shock, horror, public opinion changes. US Jewish public opinion changes. Public opinion changes all the time. Why can’t people make a case to shape public opinion, to change public opinion, to get people on board? Why say, “This is what the public in America thinks and this is the only deal the Palestinians can get?” Why outsource the resolution of the Palestinian conflict to US public opinion?

Norman Finkelstein: Well, I’m not outsourcing to US public opinion. I think US public opinion, at this point, is the weakest read. I think it’s Eur-European public opinion is quite powerful, and you c- I think it’s, uh, it’s quite feasible that you can win over not only European public opinion, but it’s important to keep in mind also European governments. I mean, as we speak, European governments are putting enormous pressure on Israel now on the question of the settlements. But do you see any European government, can you name me one, one European government…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Norman…

Norman Finkelstein: …that’s even hinted at one state? Name me one European gov… forget it, let’s not mention…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Hold on, hold on…

Norman Finkelstein: …European governments. Name me one government…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Norman, because they haven’t hinted at it today, does that mean they’ll never hint at it?

Norman Finkelstein: Name me one government in the whole world. Has the Islamic Republic of Iran called for one state?

Mehdi Hasan: If you were around in the 1930s, what would you have said to Gandhi? You wrote a book about Gandhi. What would you have said to Mandela? “Sorry guys, give up the national liberation movement – Western public opinion isn’t with you?”

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Not at…

Mehdi Hasan: “Give up all of that national liberation…”

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Nah…not at all…

Mehdi Hasan: “…and accept whatever western public opinion gives you.”

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] You’re just…

Mehdi Hasan: It’s a very defeatist posture.

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] You’re just so way off base, it’s unbelievable. Uh you read, uh… [APPLAUSE]

Norman Finkelstein: You read Mahatma Gandhi. Mahatma Gandhi’s standard was always where public opinion is. You don’t go beyond public opinion.

Mehdi Hasan: And was public opinion in favour of an independent India in the 1930s? I don’t think it was, Norman.

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Well…uh…no…Ga-Ga…we were entering the era of decolonization. This was after World War I, and then he said, in that era, yes, that’s something which is reachable, something within reach. He always calculated in terms of public opinion. And the question is…hmm…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] But you told Salma that you’ve got to stick with the two-state solution because that is where the limits of public opinion lie…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Yeah…I…

Mehdi Hasan: …and I’m saying, that’s not how the world works.

Norman Finkelstein: I…no… When I said public opinion, I did not limit myself to the United States. I said the United Nations. I said 165 countries have embraced this solution. The problem is they’ve only done it on paper, and the challenge is: how do you turn passive support into active support? And I think there I agree with Gandhi, the way you ch-, you turn passive support, which exists, including in the American Jewish community, the way you turn it into active support is you have to have mass non-violent resistance in the occupied territories, like the first Intifada, which was remarkably successful. Although it was aborted, it was a very successful first undertaking.

Mehdi Hasan: Ok, our panel are agitated to come in. Jeff Halper, you wanted to come in.

Jeff Halper: Today there is no traction to a one-state solution. The problem here is that we’re thinking in a linear way. We’re assuming that the status quo of today, the situation of today is going to continue; now how do we deal with it? This is a very dynamic situation. Um, it’s very likely… it-it’s certainly possible that the Palestinian Authority is going to leave the scene at some point. I mean, Abu Mazen, himself, is 80 years old. It could very well be the Palestin-…that tha-that the, that there’ll be a political collapse if the Palestinian Authority leaves the scene, and Israel will have to reoccupy the Palestinian cities, and maybe Gaza. Given a collapse, then that opens up possibilities for one-state solutions and other possibilities that don’t exist today, which is true.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Do you support the one-state solution in all?

Jeff Halper: I support it and I think it’s very do… and not only is it doable, but it’s the only way out, but it’s going to have to wait upon a collapse in which, in which the…the…w-what we’re talking about today becomes really irrelevant.

Mehdi Hasan: One of the issues on which Palestinian public opinion now…is now switching, and a lot of Palestinian grassroots is coming behind, is the idea of a boycott, divestment and sanctions movement, the BDS movement, of a kind of South African anti-apartheid-style movement to isolate Israel – you said Israel’s occupation is cost-free – to impose a cost on Israel. Is that something you support?

Norman Finkelstein: Totally. I was for BDS before BDS existed. Any sane person would be for it.

Mehdi Hasan: And, yet, a couple of years ago in an interview, you’ve, now infamously, referred to BDS as a cult. You said the people who joined BDS are part of a cult and they’re responsible for a potentially historically criminal mistake.

Norman Finkelstein: Yeah, because there’s a difference between a tactic and a goal. The tactic is absolutely gi-legitimate and, as I said, I’ve always supported the tactic. The problem is the goal.

Mehdi Hasan: Ending Israel’s occupation and dismantling the wall, recognizing the rights of Palestinian citizens in Israel and respecting and promoting the rights of Palestinian refugees. Which of those three goals do you object to?

Norman Finkelstein: BDS put out its call in July 2005 to coincide with the first anniversary of the ICJ advisory opinion on the wall. And the very first statement of the BDS document says, “We support international law.” And they say the first right under international law is the right of peoples to self-determination, and from that right of self-determination, they then derive three other rights. I say, of course, I agree with all of that. But Israel is also a state under international law. Israel still…also has the right to self-determination and statehood under international law. And then you have two options. One option is you have to recognize the reciprocal rights of Israel under international law because you say you’re anchored in international law. Or, of course, you have the right to say, “To hell with international law, I think it’s all nonsense, I think it’s all made by rich people against poor people,”…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] But their three goals that you mentioned…

Norman Finkelstein: Sure… But don’t pretend, “I’m for international law only when it concerns my rights.” It’s like saying, “I have the right to walk at the green, but I’m agnostic on the red.” If you have a right to walk at the green, it’s because you have an obligation to stop at the red.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Hold on; hold on, Norman…that would only count…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] You can’t…you can’t claim rights just for yourself.

Mehdi Hasan: …if…if they said they want to destroy Israel militarily, then you could say that’s violating international law. I’m not sure how demanding three rights which you agree with…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Um…excuse me, Mehdi, is Israel a state under international law?

Mehdi Hasan: It’s recognised by international law, yes.

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Ok, fine… Fine, and if B-…if B-

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] And where does the BDS not recognise Israel?

Norman Finkelstein: Ask them!

Mehdi Hasan: I have asked them…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Wait, wait!

Mehdi Hasan: I have asked them. I…I…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Mehdi, do you think it’s an accident that Israel is not mentioned?

Mehdi Hasan: Israel is mentioned.

Norman Finkelstein: Do you think it was an oversight?

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] O-…O-…

Norman Finkelstein: “Oh, we forgot about Israel”?!

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] O-…Norman, Norman!

Norman Finkelstein: Is this serious? [LAUGHTER]

Mehdi Hasan: Really, Norman? They forgot about Israel?

Norman Finkelstein: Christ sake!

Mehdi Hasan: They forgot about Israel? Omar Barghouti, the founder of BDS…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Yes.

Mehdi Hasan: …has pointed out that the majority of people on the boycott committee are two-staters.

Norman Finkelstein: That’s absolutely correct.

Mehdi Hasan: Which, which bit of international law did they not recognise?

Norman Finkelstein: That Israel is a state under international law.

Mehdi Hasan: Can you show me a statement where they say Israel isn’t a state under international law?

Norman Finkelstein: Show me a statement where they say it.

Mehdi Hasan: I did show you a statement…

Norman Finkelstein: They say… [LAUGHTER] …Have you ever asked… [APPLAUSE] …have you ever asked a BDS person where they stand on Israel?

Mehdi Hasan: Yes.

Norman Finkelstein: And what did they say? “We take no position?”

Mehdi Hasan: Salma, you’re not following international law by supporting this BDS campaign.

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub: The three calls of BDS are completely in line with international law, and the question of how you end up resolving the conflict, whether you have one state or two states, whether Israel is…is there still as a state or not, is actually a political question that international law is silent on. So, there seems to be a lot of confusion about this role of international law…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Ok.

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub: …and, to my mind, it actually seems to be a-an excuse to attack the BDS, and I find that a really extraordinary thing to do when the Palestinians have very t- few tools at their disposal at the moment to promote their rights, and to promote solidarity with their cause. So I, I want to ask you, actually, why would you use your platform, given the context that we’re in, to attack BDS so…so vehemently?

Norman Finkelstein: Well, I’m talking about BDS with a capital B, capital D and capital S. What I was asked about was the tools that are available to Palestinians. And I said, “Of course I endorse those fools…tools and I c- of course I used them and endorsed them long before BDS came along.” But under international law, which you claim I completely misunderstand, doesn’t Israel have the right to self-determination and statehood? Or are you telling me all the nations…

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub: [INTERRUPTING] I…I…

Norman Finkelstein: …in the UN, the 196 nations which admit Israel as a member state, are suffering from a delusion?

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub: They recognise it politically…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] It’s a state under international law!

Mehdi Hasan: Jeff Halper, you support BDS. You’re one of the rare few Israelis who actually thinks, “Yes, it’s right to boycott my own country in order to put a cost on it,” I believe.

Jeff Halper: No, that’s right. You know, we support BDS because, um, BDS gives the people in solidarity with the Palestinians those tools to push the governments. If it hadn’t have been for the people, we would still have an apartheid South Africa. The people were the ones that, that organised and pushed the governments to do what they should do. Governments will not do the right thing unless they’re pushed by the people.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Before I bring Norman back in…

Jeff Halper: [APPLAUSE] And that’s what BDS is about.

Mehdi Hasan: Before I bring Norman back in, Oliver, very briefly, you wanted to come back here.

Oliver Kamm: This is where the debate breaks down. Criticism of Israel is legitimate. Comparisons to the apartheid regime, to institutionalised racial discrimination, are tendentious and a disgrace. The moment you demonise Israel in that way…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] When you say it’s a disgrace…

Oliver Kamm: …you are outside the political consensus that has built up..

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] When you say it’s a disgrace, are you aware that the ANC, which led the struggle against apartheid, has endorsed BDS?

Oliver Kamm: Not all of them, by any means.

Mehdi Hasan: Er, Norman, do you regret now, two years on, calling the people who campaign for those three goals, which you say you share, Palestinians who see no other way of ending the occupation than adopting an apartheid-like struggle… do you regret calling them members of a cult?

Norman Finkelstein: I don’t regret calling them members of a cult if they act like a cult.

Mehdi Hasan: You see yourself as a radical. You said in a recent biographical film about your life, called American Radical, that you see the world as a, quote, “radically unfair place which requires a radical change.” And yet on Israel-Palestine your position isn’t radical at all. It’s safety first, it’s establishment-friendly, it’s pro- the consensus of the UN Security Council and, uh, other opinions. You’re not a radical on Israel-Palestine, you’re quite conservative.

Norman Finkelstein: You know, that’s like saying, we’re facing a…a meltdown on the economy in the western world. So you have to deal…what are you going to do about it? Ok, I’m gonna be real, uh, radical. I’m going to advocate the abolition of money. Well, that’s a really radical position. It really is. I mean, and, according to Marx, that should solve everything because then we’ll be in communism. But what does that radical position have to do with the real world? That’s a cult. I want to make the world a better place so I’m trying to look at the real material conditions in the real world, the real political limits that are imposed upon us, and figure out, within those limits, what’s the maximum we could hope for? I didn’t say the minimum, I didn’t even say the moderate. I said, “Let’s look at what the maximum is possible.”

Mehdi Hasan: Well, we’re going to have to leave it there. We’ll come back in Part Two. We’re going to take a break right now on Head to Head. Join me in Part Two where I’ll be talking, uh, to Norman Finkelstein about some of the personal battles he’s had to wage, uh, especially with the Jewish community. And we’ll also be hearing from our audience here in the Oxford Union. That’s after the break. [APPLAUSE]

Part two

Mehdi Hasan: Welcome back to Head to Head on Al Jazeera. Uh, we are talking to Norman Finkelstein, the US author, academic, activist. Uh, Norman, you’re a well-known intellectual. You’ve published several critically-acclaimed, bestselling books. After your book The Holocaust Industry came out in 2000, you were accused of being a, quote, “self-hating Jew”. Uh, what’s your response to that quite common, yet very serious accusation?

Norman Finkelstein: Well, my response is a pr- uh, a completely rational one. Let’s say it’s true. For arguments sake, I’m a self-hating Jew. What does that have to do with the facts? I mean, if Einstein was a self-hating Jew, for arguments sake, does that mean E does not equal MC2? What do the facts have to do with what I am or what I’m not? If I were a self-loving Jew, would that mean everything I say is true? [LAUGHTER] So… [APPLAUSE]

Mehdi Hasan: Do you think sometimes you, maybe, are your own worst enemy? You are quite provocative, you’re quite controversial. Do you think that that is part of the problem with Norman Finkelstein? That you pick fights what everyone and anyone and you end up doing yourself down?

Norman Finkelstein: Well, first of all, I don’t think politics is a popularity contest. Uh, when you get too popular with the people, there’s probably some problem. And there is part of me that does believe that. I am not happy at all if there is any hostility from the people who are actually suffering – uh, namely the Palestinians. And I can see Miss Karmi is not pleased with what I’m saying, and that does bother me, I have to tell you. The rest of the people, I couldn’t care less.

Mehdi Hasan: Your book The Holocaust Industry argues that the memory of the Nazi genocide, in which most of your family perished…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Mmm hmm.

Mehdi Hasan: …has been used to excuse Israel’s behaviour in the occupied territories, to justify US support. It’s an argument a lot of people make. It’s an argument I’m sure many people in this room would agree with; people watching at home. But some people would say you phrased i- that argument in such an overly-provocative, even offensive way. Look at the chapter headings…the book here…”The Double Shakedown”, “Hoaxes, Hucksters and History”. How can you say that doesn’t play into anti-Semitic stereotypes?

Norman Finkelstein: Well, it’s kind of funny, I mean, just as a personal story, and I hope my publisher is not going to be offended. But when the book came out it was really j-, it was originally called, “Theory”, “Practice”, and “Examples”, the three chapter headings. And he says, “That’s so boring! We have… [LAUGHS] …to make it more exciting because many people…” [LAUGHTER] And… those chapter hea-headings were cited by th- my university when they denied me tenure, so I blamed him for the whole thing. But uh… [LAUGHTER]… that aside, on a more serious note, when the book came out in 2000, I mean, it evoked a kind of hysteria, and now what I say is, uh, kind of commonplace. So if you take the case of, um, the former…uh… speaker of the Israeli Knesset, Avraham Burg, he writes a book on the holocaust, he refers to the “shoah industry”. Now, when I used the expression “the holocaust industry”, it elicited all these horrors and shrieks and, “What are you saying? Anti-Semitic! holocaust denier!” And now it’s even commonplace among Israelis to refer to a sho…a shoah industry.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] You say commonplace… You say commonplace. In your own words, you once said, “I’ve never been able to get a permanent teaching job in the US.” Why do you think that is?

Norman Finkelstein: Uh, I’ll simply say: the facts, as I understand it, speak for themselves. Uh, if you take the example of the last place where I was employed, which was a university in Chicago, um, when they denied me tenure, the statement that they delivered upon denying me tenure s-said that, uh, Finkelstein has been a, uh, excellent teacher and a prolific scholar. So, uh, if I was an excellent teacher and I was a prolific scholar, uh, I shouldn’t have been denied tenure.

Mehdi Hasan: So why were you?

Norman Finkelstein: Um… well, um… I think people have to draw that conclusion on their own.

Mehdi Hasan: Many Jewish people claim that you are anti-Semitic…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Mmm hmmm.

Mehdi Hasan: Then I think that would be a problem for the Palestinian people, I think, who would see…who have seen you as a champion over the years. You were, as you say, very popular. Some people…one person called you a “rock star”. Uh, I think that would be a problem if it turned out that you were actually anti-Semitic.

Norman Finkelstein: Actually, I think that would be a problem also. Uh, my own view is that I do more personally to fight anti-Semitism by my example in the Arab/Muslim world than probably almost any other Jew that I know.

Mehdi Hasan: Oliver, Norman says that, just by his example, just by writing this book, highlighting these issues, he’s actually done more to combat anti-Semitism than most other Jewish public intellectuals. What do you say to that?

Oliver Kamm: That’s not the view of, er, of historians who reviewed his book, er Peter Novick, the author of The Holocaust in American Life, described it as pure invention and compared it to the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. My criticism of Norman Finkelstein is slightly more prosaic. I have no problem at all with writers being provocative – it’s what I am paid to do – but you’re not very good at it, you’re a hack writer, you made a factual error!

Norman Finkelstein: Well, you’re certainly entitled to your opinion. I don’t know of any expertise…

Oliver Kamm: [INTERRUPTING] Who else’s opinion…

Norman Finkelstein: I don’t know…I don’t know of any expertise you have on the topic.

Oliver Kamm: You understated, by a large number, the number of holocaust survivors.

Mehdi Hasan: Ok, that’s the last question…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Ok…

Mehdi Hasan: Very briefly.

Norman Finkelstein: I would like to answer that.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Very briefly please.

Norman Finkelstein: I don’t claim at all to be an authority on the Nazi holocaust. The book The Holocaust Industry is not about the Nazi holocaust. It’s a book about how the holocaust has been rendered in popular opinion and in so-called scholarship. The figure I got of under 100,000 survivors of the Nazi holocaust, it didn’t come from me. It came from Raul Hilberg. I think you’ll agree – if you have any knowledge of the Nazi holocaust, which is doubtful – but if you have any knowledge of the Nazi holocaust, you’ll know that the world’s leading authority on the Nazi holocaust, bar none, was Raul Hilberg. He was in a class all his own. Raul Hilberg praised The Holocaust Industry. In fact, he said my conclusions in the book were conservative. Now Raul Hilberg was begged by the Hol-…US Holocaust Museum and his close friend Elie Wiesel to remove his name from the book. And he said, “No, I refuse to remove my name from the book, because what Finkelstein wrote is true.” He said, “Finkelstein’s place in history, as a historian, is secure,” and what was done to me was “a travesty”. So, when you come along and say, “You’re a hack writer,” I attach as much value to that as I attach to the d-…to the dust on this floor. [APPLAUSE]

Mehdi Hasan: Let me ask you this…let me ask you this… Let’s carry on. You’ve both made your points forcefully. How do you make sure that you criticise Israel – this is a j-… open question, kind of, I think people will be interested in knowing your take. How do you… make sure that your criticism of Israel doesn’t cross into anti-Semitism? Because some people do. There are people who are anti-Zionists and are anti-Semites. There are people who are anti-Zionist who are not anti-Semites. I’m just wondering what your view is.

Norman Finkelstein: I am – and I’m not trying to play the holocaust card – but I am the son of survivors of the Nazi holocaust; real survivors – Auschwitz, Majdanek. Every single member of my families, on both sides, was exterminated during the war. I’m very sensitive to that charge. The holocaust denier charge, I think, is, like, completely insane when it’s applied to me, because anyone who knew me growing up would say…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Ok, but what…

Norman Finkelstein: …if anything, I was a holocaust affirmer, not a holocaust denier…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERUPTING] Ok, but back to my question.

Norman Finkelstein: …i.e. I never stopped talking about it. As to your question, I think the problem is: what do you do with motives? How do you define a person’s motive? And I don’t know how you divine a person’s motive. Yes, it’s true that sometimes people are going to be making statements because they…they harbour anti-Semitic sentiments, or are har-hardcore anti-Semites. And then the only thing you can do, in my opinion, is try to refute it on the basis of facts.

Mehdi Hasan: Jeff Halper wants to come in. Jeff Halper from the Israeli Committee against House Demolitions.

Jeff Halper: I just wanted to…to register a reservation about linking criticism of Israel to anti-Semitism. Israel is a country. And, in fact, Israel…the whole idea of Zionism was we’re not Jewish, we’re Hebrew, we’re Israelis. Uh, Jews are something else, uh…the Jewish… you know, most Jews never went to Israel. You can’t make Israel representative of Jews, and you can’t hold Jews accountable for what Israel does. So I-I really think this… We’re playing into what Israel calls “the new anti-Semitism,” that was invented by the Israeli government that says any criticism of Israel is anti-Semitism. I think we have t-to negate that a-and therefore I just wanted to say here that I was a little uncomfortable with the idea that somehow criticism of Israel has anything to do really with anti-Semitism. [APPLAUSE]

Mehdi Hasan: Jeff, is it easier, in your view, as an Israeli, do you think it’s easier to criticise Israel inside of Israel than it is from outside of Israel?

Jeff Halper: Of course.

Mehdi Hasan: Is there more criticism of the Israeli government at home than aboard?

Jeff Halper: In Israel, just like in any other country, to criticise your government is a…is a normal thing. I mean, if you criticise the Cameron government here…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Ok.

Jeff Halper: …you’re not anti-British, and I think Israelis, you know…this is a…this is a whole conversation that has to do with more with the diaspora than it does inside…inside Israel.

Mehdi Hasan: Ok, well let me a…let me put that point to Oliver. Oliver, you write for a newspaper in the United Kingdom. Do you…do you agree with what Jeff’s saying about what…how the criticism inside of Israel is much more ferocious and open than outside of Israel?

Oliver Kamm: I’ve never met someone who believes that criticism of Israel, of Israeli government policy, um, much of which I’ve done myself…

Jeff Halper: [INTERRUPTING] Right.

Oliver Kamm: …is inherently anti-Semitic.

Jeff Halper: But the Israeli foreign ministry…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRRUPTING] Ok.

Jeff Halper: …er, about five or six years ago, consciously and deliberately developed a concept that’s called “the new anti-Semitism” that says exactly that.

Mehdi Hasan: Let me just bring in Salma Karmi here who… you’re a Palestinian, uh, based in Britain. Do you feel as someone who wants to, kind of, campaign for your people’s rights, campaign against occupation, do you feel inhibited in what you can and can’t say about the conflict?

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub: I think there is a certain inhibition for Palestinians and for those who are in solidarity with Palestinians, which is that whenever we want to talk about the nature of Zionism or, for example, the nature of the state of Israel as it is currently constituted, we run into this criticism that we’re either anti-Semitic or that we’re not respecting international law, or that we’re calling for the annihilation of the Israeli people, when we’re not. And we want to be able to have a legitimate debate about the principles that underpin the state of Israel and why they have caused so much suffering for the Palestinians and how the continual…the continuance of Zionism is going to continue the conflict, in fact, and continue the dispossession of the Palestinians. But whenever we…but when we try to do that I-I’d say there are definitely people th-that shut down the debate by levelling this charge of anti-Semitism or de-legitimisation of Israel as well, as it’s…as it’s been called.

Mehdi Hasan: Ok, um, let’s go to our audience here who have been waiting very patiently here in the Oxford Union. Raise your hands high and wait. Let’s go to the gentleman here in the front row. Let’s start with you in the red tie.

Audience participant 1: I’m a Palestinian, born in Nazareth, pre-Nakba years. Therefore, I consider myself a Nakba survivor. As an architect, I use my metaphor: you never plaster over a crack. Which begs my question, and that is: why do you and other colleagues, eminent people, try to plaster over the cracks of the Palestine issue; an issue that has started in the mid-1800s, and manifested itself in the great tragedy in the 20th century, the Palestinian Nakba?

Norman Finkelstein: I think going back to 1800 or going back to 1600, uh, it’s sort of like, to me, it’s like what the Zionists say, “Let’s go back to when there was this Jew- Judean k-…uh…kingdom in…uh…Palestine.” I say, well, maybe there was, maybe there wasn’t. I don’t know and frankly, I don’t really care, because I just don’t think it has much to do with trying to achieve a reasonable resolution of the conflict now. The current political consensus calls for…they use the term, “a just resolution of the refugee question based on 194,” which is not exactly implementation of the right of return. And then we have a question. The question is: what’s the maximum a political movement can extract politically from that legal right. If we can mobilise a powerful enough movement, we probably can extract more from that right.

Mehdi Hasan: I’m going to go to the gentleman in the white jumper there on the third row back.

Audience participant 2: Is there surely no strategy that Palestinians in civil society or their leadership could adopt to actually convert the cult-like international community support for a two-state solution into something, towards a one-state solution?

Norman Finkelstein: Well, at this point, Palestinian, uh, political will, for perfectly understandable reasons, that will has been depleted. Palestinians feel hopeless, they feel cynical, everything you can imagine. Palestinian people, like everybody else, are normal. And after suffering from so many defeats, there’s going to be a large amount of cynicism, hopelessness, and the every man for himself mentality. But are there possibilities here? I think there are very big possibilities. Let’s take one example. If Palestinians were to march on the wall, with a…a million Palestinians, we’ll say, holding up a sign, “Enforce the law. Dismantle the wall.”

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Ok…

Norman Finkelstein: You said I’m not a radical and, in some sense, there is an argument there, because I’m trying to find a slogan, a solution which will resonate with most of world opinion. “Enforce the law” has a real possible resonance. So I think there are possibilities if Palestinians find the inner strength and, I admit it, a lot of self-sacrifice in order to achieve the goal.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Do you think…do you think if they went up and, with a million people, stood up with a sign saying, “One person, one vote,” that wouldn’t have an effect on the world?

Norman Finkelstein: No, I don’t think it will have because if you hold up a…a…a sign that says you want to dismantle the Israeli state, you want one state, yes, it will have exactly zero resonance in the international community.

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] And yet…and yet Ehud Olmert, former Prime Minister of Israel said, “If Palestinians were to say one person one vote, Israel is finished.”

Norman Finkelstein: Well…

Mehdi Hasan: Olmert said that.

Mehdi Hasan: Let’s go back to the audience. Lady here with the scarf.

Audience participant 3: Would you not, I mean, say that, at this point, maybe it’s a blessing in disguise that the two-state solution is falling out of public opinion because the unforeseen circumstances that might come from that will be, like, um, op-oppression of the Palestinians in the Israeli state and more division between the Palestinians and the Israelis that will, in the end, cause more human rights violations in Israel itself?

Norman Finkelstein: I don’t know how the disappearance of the only, at this point, practical possibility for achieving some degree of justice in the conflict, the fact that it’s not going to be possible, why that would be a positive development. The fact that something is bad doesn’t mean that something good is then on the horizon. It could be worse.

Mehdi Hasan: Let’s go back to the audience. Gentleman there.

Audience participant 4: Thank you. Uh, I think that the two-state solution that you are now proposing is basically is used kind of like to protect the Israeli interests o-on the ground now by keeping the settlements without addressing the issue of Pal-…of the Palestinian refugees and the issue of Jerusalem.

Mehdi Hasan: Ok.

Norman Finkelstein: It’s a kind of paradox, this kind of discussion, because I think it’s forgotten that it was the PLO executive committee that endorsed the two-state settlement. It’s like history is all being effaced and whitewashed. And now it’s as if you’re saying I’m some sort of collaborator or traitor because I’m endorsing the position which the Palestinians endorsed during the height of their self… If you read Shafiq al-Hout, a respected former member of the PLO, he said, “We endorse the two-state settlement during the height of our confidence and our belief in ourselves,” namely during the first intifada.

Mehdi Hasan: If the polls, which cl-…show that every year the number of Palestinians who support a one-state solution goes up year after year after year, and by age, the younger you get, the more support there is. If tomorrow the polls show, or next year, or two years, the majority of Palestinians, both in the West Bank and abroad, want a one-state solution, one person one vote, will you support them in that?

Norman Finkelstein: Uh, in 2-… in 2001, 2002, in the occupied Palestinian territories, the majority of Palestinians supported the suicide bombings. Now I could s-, I could understand why they supported the suicide bombings, I can understand the rage, the anger and everything else, but in the name of supporting Palestinians, am I obliged to support the suicide bombings?

Mehdi Hasan: Are you really comparing support for suicide bombings to support for one person one vote?

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] I don’t think the… No, no I wasn’t. What I was saying…what I was saying was…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Not the best of analogies.

Norman Finkelstein: What I was saying was the fact that the majority of the people might support a particular position doesn’t compel me, as a separate individual, to embrace that…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Ok.

Norman Finkelstein: …if I think it’s unrealistic.

Mehdi Hasan: Fine, I’ll take that as a no. We’re going to go to the gentleman right there at the back with his hand up. Yes, you, sir, you can stand up. Yes, you.

Audience participant 5: I wonder, do you agree with Professor Noam Chomsky who, you know, thinks that language has a particular significance here, and that the peace process being whatever John Kerry says the peace process is, you know, “process” is extremely corrosive, or that “settlement” sounds non-invasive, where, in fact, the reality is something rather more sinister?

Norman Finkelstein: It’s obviously not been a peace process; it’s been an annexation process. So, the peace process, at least the current phase of it, the current phase of it is said to have been initiated at Oslo in 1993, and then you look at the results. There were about 250,000 settlers in the occupied Palestinian territories in September 1993. The figure is now, 20 years later, now it’s about 550,000. So, judging the process by the results, there hasn’t been a peace process, there’s been an annexation process.

Mehdi Hasan: Ok.

Norman Finkelstein: And the Israelis and the Americans use the peace process as a fig leaf to conceal the annexation.

Mehdi Hasan: Back to the audience. Uh, gentlemen here on the second row with the jumper on.

Audience participant 6: Thank you. I’m a Palestinian. Now, I’m confused, and I think, uh, you are confusing all of us. Are you pro-Palestine, or are you…?

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] I’m not pro-Palestine, absolutely not. I’m pro-justice. I have no interest in Palestine.

Audience participant 6: Right, or are…or are you an Israeli peace negotiator here?

Norman Finkelstein: I’m not!

Audience participant 6: Because what…

Norman Finkelstein: I’m not either.

Audience participant 6: Because what you are saying…

Norman Finkelstein: I have no interest…

Audience participant 6: You are causing…

Mehdi Hasan: Let him finish his question, then you can come back. Make your point.

Audience participant 6: Norman, you are causing a division amongst the international pro-Palestine activists by not accepting, or by not r-…or b-by not respecting what they are demanding for: one-state solution.

Norman Finkelstein: Can you show me any evidence – a jot, a scintilla, a tiddle of evidence – that the Palestinians, uh, i-in the majority, or their civil society organisations support one state?

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub: [INTERRUPTING] You know that there is unreliable data.

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Where…where…where is that from? Show me the evidence – I’m curious.

Mehdi Hasan: Ok, let Salma…let Salma briefly speak and then we’ll go back to the audience.

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub: I mean, if you spent any time on the ground in Palestine, or in the diaspora Palestinian communities, this issue would be obvious to you. When Palestinians are asked explicitly what do they think is politically viable, they’ve been fed on the two-state idea for so long, many of them will say, “Two states but w- you know, we can’t imagine anything else.” But if you ask them about the reality that they actually want, it’s in accordance with the one-state idea, and if you presented them with a…

Mehdi Hasan: [INTERRUPTING] Ok…

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub: …strategy to achieve it, they would absolutely support it.

Mehdi Hasan: Ok, we’re gonna go back to the audience now. Gentleman here in the front row.

Audience participant 7: A-as you’ve said, the majority of Israelis and Palestinians, as far as we know, do support the two-state, uh, solution. However, do you think that some your, um, support for groups that support violence and rejection like Hezbollah, um, actually doesn’t support that ma-majority of what you call… um and I…I would agree is progressive public opinion, actually undermines that and supports the rejectionists.

Norman Finkelstein: Well, first of all, there’s too many things attached to me which don’t, uh, reflect my own opinions. I don’t believe a majority of Israelis support a two-state settlement – there isn’t a scratch of evidence to support that. What the majority of Israelis will support is, uh – probably around 70 percent – will support, uh, a settlement of the conflict where Israel, uh, annexes the…the settlement blocks, the major settlement blocks, and annexes most of Jerusalem and nullifies the right of return. That’s what you…you find, uh, maybe as many in certain t-…uh…polls, as many as 95 percent. But when you talk about actual settlement on the June ‘67 border, uh, and a Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem, a significant Palestinian capital in East Jerusalem, uh the support goes down to ten or 15 percent.

Mehdi Hasan: I think the point your critics would make is that a group like Hezbollah ain’t so enthusiastic about the two-state solution and yet you’re…

Norman Finkelstein: [INTERRUPTING] Right, but I don’t see…I don’t…

Mehdi Hasan: …willing to come out and defend them in public. I think that’s the…the criticism.

Norman Finkelstein: There’s no confusion here. I never said I support Hezbollah. Hezbollah has the right and it did, uh, to my, uh, to my thinking, uh, displaying an enormous amount of courage and heroism and discipline. They expelled foreign occupiers from their country. And why shouldn’t we celebrate those occasions? I mean, in any other country in Europe, uh, the people who were part of the resistance, people who expelled the Nazis from their country, uh, we all celebrate the resistance. So, why shouldn’t we celebrate it? Uh, because they’re Muslims? [APPLAUSE]

Mehdi Hasan: Uh, let’s go back to the audience. Lady there in the audience – second row up there.

Audience participant 8: You just said that you support violence. Before, you said you support an anti-violent resistance. Could you please explain the contradiction?

Norman Finkelstein: I don’t consider it a contradiction. In certain circumstances, in my opinion, and I’ve studied Gandhi pretty closely, Gandhi’s tactics can work in certain circumstances. They can’t work in other circumstances. If you’re in the middle of a forest in India, uh, and the Indian army is coming in and just wiping you out, nobody in the world cares, because nobody even knows what the heck is going on in that little forest in India. So non-violence is not going to work there. But in a place like Israel-Palestine where, for historic reasons, Palestine is very much in the eye of the world, it’s very much on the international agenda, in places like that, yes I think non-violent resistance can work. I do not think it could have worked in South Lebanon – nobody gave a darn about Israel’s occupation of South Lebanon, just like nobody gives a darn about Israel’s occupation of the Golan Heights.

Mehdi Hasan: Final question to you before we finish… [APPLAUSE]

Mehdi Hasan: You once said to some fans of yours, “Please don’t put me on a pedestal because you’ll end up being disappointed.” Do you think that’s how a lot of people, not just in the Jewish community, but these days in the Palestinian community feel about you? Disappointed, betrayed even?

Norman Finkelstein: I’m the same person as I always was. Uh, the only difference is, it’s not me that’s changed, it’s the international community, public s-sentiment. There’s been a huge change, not least among the American Jewish community, and now you have something to work with. You have real possibilities, real hope that something can be done and so, uh, now I seem so moderate. But the difference between me and many people in the BDS is I’m really happy about that fact. We finally have a breakthrough in public opinion; we have somebody to talk to. And other people think, “Well, no, that’s not good, let’s strike a more radical pose, let’s try to be really radical and let’s be really chic, and let’s be…” Especially when you’ve got tenure, you can be really radical, and so they start striking all of these radical poses, uh, which have no connection with reality and they’re so… uh defeatist of the cause. We have a real possibility now. The thing we struggled for…f-for decades, we now have a public that’s willing to accept the terms of a settlement which, as I said, the Palestinians themselves endorsed in 1988. And now we have a chance, and people are saying, “ah, two states. Passé. Liberal Zionist. We need something more radical.” And that, to me, is very frustrating, because I think now we have real possibilities. [APPLAUSE]

Mehdi Hasan: Norman Finkelstein, thank you very much for joining us on Head to Head tonight. Thank you all for being here. [APPLAUSE] The debate will continue online. Join us next week here for Head to Head. Goodnight.

Audience: [APPLAUSE]