Israeli anniversary voices

Sixty years on, Israelis reflect on the creation of their state.

|

As the 60th anniversary of the creation of the state of Israel approaches, Al Jazeera’s special series The Promised Land? tells the story of its origins, violent creation and modern-day reality through the stories of individual Israelis.

| The Promised Land? | ||||

|

Uri Avnery left Germany for Palestine in 1933, when he was just 10 years old. A former Knesset member, he is now a leading peace activist.

“My family was an old established family in Germany. My father was a banker – we were quite well to do. When we came to Palestine we became very, very poor overnight.

When the Nazis came to power, my father was one of the few German Jews who realised immediately that we should leave immediately, and this we did.

It was a very adventurous experience for me.

I remember arriving by ship opposite Jaffa. It was a huge experience for a young boy. I loved the country on sight. I loved everything. I loved Jaffa which at that time was a purely Arab town.

It was not only a wonderful feeling that we were out of Germany – it was an even more wonderful feeling that we were entering a new world.

For a child of 10 this was a wonderful experience – everything was different, everything was new. The Arab language, the smells of Jaffa – everything was so new and wonderful.

My only wish was to completely eradicate the first 10 years of my life. It felt like a new birth.

[David Ben Gurion] says when he saw Jaffa he was disgusted – what an awful city, what a terrible language and what awful smells – everything was horrible and he said “Is this the land of our fathers?”

So I think the first impression says a lot of what happened afterwards.

Imagined country

For most of the Zionists who came to this country, I would say it was a terrible disappointment – they were not prepared, they really thought the land was empty. And therefore I think there was a kind of pushing away of the reality of Palestine right from the beginning, in favour of an imagined country.

|

| Uri as a member of the Irgun in 1940 |

They wanted to reshape everything in the country.

And you see it everywhere. You see it in the architecture, you see it in the outlay of the cities, everywhere you see that the Zionist movement, when it moved into this country, they did not come to a country that they accepted. They came to a country that they wanted to change completely, to reshape.

They never accepted Palestine as it was – which was an Oriental, Arab, mainly Muslim country.

From the first moment, this movement was determined to wipe out everything of what this country was in the last 2,000 years and create a new country. And of course, they did.

All of us who came to this country had only one wish – to completely forget the past and become local, and adapt ourselves, and pretend that we were born in this country.

For example, all of us the moment we were 18 years old, we shed our names. We changed our German, Polish, Russian names, whatever, and adopted a Hebrew name. That was the done thing.

Foreign occupation

I joined the anti-British underground when I was 14 years old. The British were considered enemies. For people of my age group the British were foreign rulers, British rule was a foreign occupation.

For us it was quite clear – we wanted to take over the country, we considered it our country, and the British had nothing to do here.

It was not just a question of the British being a foreign government, but it was also a question of opening the gates of the country to Jewish immigration – this was the most burning question right from the middle of the 1930s up to the last day of the British mandate before the state of Israel was founded. It was all about immigration.

From the other side, from the Arab side it looked exactly the same, but opposite – here come the Jews flooding our homeland, and really want to take away our homeland from us.

So it was not just the Jews against the British, it was the Jews against the Arabs. It was a triangle in which everybody hated everyone else, and fought everybody else. And from 1936 on, it was war.

Separation

There was a complete separation. Jews and Arabs did not mingle, did not mix, there was no connection at all.

Therefore you could live in Tel Aviv and never meet an Arab at all, except some fruit vendors in the streets. Like today actually, there was no great difference between then and now. Everybody who tells you differently is imagining things.

|

| Uri with Yasser Arafat in Gaza, 1994 |

At that time the Irgun killed Arabs en masse. We put bombs in the Arab markets of Jaffa, of Haifa, of Jerusalem – in retaliation for Arab bombs against Jewish buses and so on.

We were quite clear what we were fighting for. We were fighting for Palestine becoming a Jewish state. This was what it was all about.

In 1936 when I was still in school, the so-called Arab revolt started – which was an uprising of the Arabs of Palestine against the British and against the Jews – mainly caused by the great immigration wave coming from Nazi Germany.

Living in the underground was an extraordinary experience for a boy of 15 – it overshadows everything else you are doing in your life.

It kind of gives you a feeling of superiority because you walk in the street and you have a pistol wrapped between books under your armpits, and you know that people are being hanged for keeping weapons. It gives you a wonderful feeling of danger, of living.

I left it [the Irgun] because there came a time when I was 18 or 19 years old when I thought that this approach to the Arabs, and this terrorism against the British – I couldn’t approve of it any more.

It was a very great crisis in my life. I remember after I stood up and said “I’m leaving” it was a shattering experience. I remember that for a few days it was like dying. I lost all my friends overnight.

‘No choice’

The actual day the British were leaving and the state of Israel was announced for us actually went by virtually unnoticed. It was not important – for already we were engaged in major battles – the war was on, and we were in the middle of a war.

From the first moment it was clear that the Arabs couldn’t possibly accept it as for them it meant that their country is being taken over by foreigners. We knew that there was going to be a major war.

| The Promised Land? |

In a way, it was a liberating feeling I must say, because the tension is building up – it was like a spring which is getting tight, and suddenly it’s released.

My first engagement was attacking an Arab village not far from Latrun, between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

We all tried to look very brave. We were all very afraid – a combat soldier ahead of an engagement is afraid not really of the enemy, but of not standing up, of not proving oneself.

The slogan of the war was “there is no choice”. And we actually felt exactly like this.

We knew that if we were going to loose the war, we would loose not only the war, but everything.

It was an ethnic war. It was different from the usual wars of which you read in history books.

It was like the war in Bosnia, in which you have two peoples, both of which claim the whole country as its motherland, denying the right of the other side completely, not even recognising the other side as being there. And to take hold of as much of the country as you can without the enemy population – this is what ethnic cleansing means.

This was a war of ethnic cleansing, not just from our side, but from both sides, because very few Arabs remained in the territories that we conquered, and not a single Jew remained in the very small territories that the Arabs conquered.

We never really thought that we are going to loose the war. It was a theoretical possibility, but somehow we had a supreme self confidence.

I had a riffle with a swastika on it, because these arms were produced in Czechoslovakia for the Germans and when the world war ended they remained in stock in Czechoslovakia and Stalin – who supported the state of Israel in the darkest hour – told the Czechs to send the arms to us.

We had German airplanes, and the Egyptians had British spitfires, so when you had a German and a British airplane fighting it out over your head, the German was ours, and the British was theirs!

Last line

When the Egyptians came to Ashdod our commanders told us that you are the last line defending Tel Aviv, which gave us a lot of motivation of course. And we really were.

|

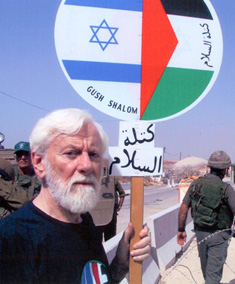

| At a demonstration at a-Ram checkpoint in 2002 |

The Egyptians could easily have reached Tel Aviv actually – because if they had made a determined push, we had nothing to hold them up with.

About July the table turned. We had already enough arms; we had already an efficient army working. The Egyptian army was very inefficient.

In the second half of the war after the Arab population had been pushed out to a great extent, some of the Arabs tried to come back to their villages. Our order was to kill them, each of them.

I have some pictures in my mind which I do not let come to the foreground – of peasants, fellaheen, being killed at close range – unarmed. In a war you see many things, and I got them out of my system by writing about them.

Decimated generation

When the war started in this country we were 635,000 Jews and 1,200,000 Arabs – that’s 2 to 1. Of these 635,000 Jews more than 6,000 were killed in the war – which means one per cent of the whole population.

My whole generation was decimated – killed, wounded and so on. And I think there was hardly anyone who was not wounded in the end. And it has had a devastating effect in many respects that people are not conscious of. It had a very great effect on what we were trying at that time to create in this country, a new culture, a new civilisation.

I think Israel after the war of 1948 was a different country from before the war – and immediately there came a huge wave of new immigrants from the displaced people of Europe and from the Oriental, Islamic countries. Israel’s still changing, it’s changing all the time.

Of course, it’s completely different from what we could have imagined. It’s changed in every respect.“