Mubarak trial viewed as symbolic test

No modern Arab leader has been tried by his own people, but some want to focus on current abuses, not old ones.

|

| Visceral anger at Mubarak and his inner circle helped unite Tahrir Square during Egypt’s 18-day uprising [EPA] |

When ousted Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak appears in a hastily assembled Cairo courtroom on Wednesday – if he appears at all – it will be a moment unlike any the Arab world has seen in its modern history: a leader overthrown by his own people and put on trial in plain view.

Zine el Abidine Ben Ali, the ousted ruler of Tunisia, fled to Saudi Arabia and has been tried and convicted in absentia.

Saddam Hussein, president of Iraq for 24 years, was tried and executed after a foreign invasion led by the United States. Other rulers have been brought down by military coups and summarily killed or sent into exile.

Mubarak’s trial will be unprecedented – a televised catharsis for millions of Egyptians who took to the streets in January and February united primarily in their hatred of the regime he oversaw for 30 years.

But on the eve of trial, many wonder whether the ailing, 83-year-old Mubarak will even appear in person, and some say his trial – while necessary and symbolic – matters less than improving the Egyptian economy and defending the civil rights which protesters thought they had earned over 18 days of bloody revolution.

Murder and corruption charges

|

| If Mubarak attends, he and the other defendants will be put inside a cage in a specially constructed court [AFP] |

If Mubarak appears, he will not be alone.

The former president’s case also includes his two sons, Gamal and Alaa, former Interior Minister Habib el-Adly, and six senior police officers.

Hussein Salem, a businessman in the petroleum and gas industry, has been charged but fled to Spain and is still being held there.

Mubarak faces an array of allegations. The most prominent and emotionally charged are those tied to regime-sponsored violence against protesters that left 850 people dead and thousands injured during the uprising.

Mubarak, Adly and the high-ranking police officers are charged with premeditated and attempted murder in connection with those deaths.

Prosecutors allege that Mubarak either ordered or allowed the killings to occur, while Adly and the others spread chaos and disrupted security by withdrawing most of their security forces from the streets after January 28, the bloodiest day of the uprising.

Mubarak also faces corruption charges related to gas deals and abuse-of-power charges for illegally acquiring land and property for himself, Gamal and Alaa.

Prosecutors have specifically alleged that Salem gave Mubarak and his sons a “palace” and four villas in Sharm el-Sheikh, collectively worth more than $5m, in exchange for the state giving away land for Salem’s companies.

Live broadcast

Alaa, Gamal, Adly and the other officers are being held at Cairo’s Tora Prison, along with a host of other former regime officials.

They will be transferred to a police academy on the outskirts of the capital, in an area known as New Cairo, where a special courtroom has been constructed. Mubarak will reportedly fly in by helicopter.

Judge Ahmed Rifaat, the head of the Cairo Appeals Court, will preside over the trial, probably alongside two other judges.

|

| Few members of the security forces have been arrested over the violence that left hundreds dead [GALLO/GETTY] |

The proceedings are set to be broadcast live on state television, but attendees – including families of murdered protesters – are banned from bringing in cameras, mobile phones and any other recording equipment.

Many journalists, including all those who applied from Al Jazeera, have been denied special permits to attend.

Some activists consider the trial more a symbolic sideshow than the main event: pushing political reforms and restraining the power of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces that runs post-revolution Egypt.

Mona Seif, who has for months advocated for the abolition of military trials used to prosecute petty crime and peaceful protesting, said she is more concerned with ongoing abuses than whether Mubarak shows up.

“Most of the officers who took part in the deaths of the [protesters] were not prosecuted, were not charged, and many of them … are still working,” she said.

More than 120 people were arrested on Monday when military police and security forces broke up an ongoing sit-in at Tahrir Square that included many relatives of slain protesters.

They are being held in a military jail and may face military trials that human rights groups describe as abusive and lacking transparency and due process.

Thousands of other civilians have faced similar unfair proceedings, activists say.

For Seif, Mubarak’s trial matters mostly in how it may affect the momentum of protesters on the street.

Some worry that the appearance of the longtime president in the dock will inflame those who are still sympathetic to him, but Seif said she believes the anger of the “ordinary people” who gathered in Tahrir Square during the uprising is stronger.

“For many people, he [embodies] the corruption of the whole regime … all the human rights abuse they had to endure for tens of years, and … his removal is the first victory for this revolution,” she said.

“So it is very important for people to see him in trial, to sort of be assured that this revolution is really going forward.”

Economy first

Ashraf Naguib, who runs the Global Trade Matters think tank and once served on a membership committee in Mubarak’s National Democratic Party (NDP), said the trial is an opportunity to “vent” and something people feel they need to “get out of the way”.

Naguib says he is in favour of trying Mubarak but believes the murder of protesters was just one episode in the NDP’s decades-long mismanagement of Egypt, which has led to dire poverty, decrepit infrastructure, poor medical care and a failing economy, the effects of which have arguably led to thousands of needless deaths.

Mubarak, Naguib said, was the head of a mafia-like cadre of high-ranking NDP members who controlled policy in Egypt.

As the president, Mubarak deserves responsibility, but dozens of subordinate businessmen and politicians contibuted to the country’s downward track and endemic culture of bribery and influence, he said.

“You have to understand, the whole of Egypt is corrupt. I am guilty of giving 10 pounds or 20 pounds to the police so I can double park my car,” he said.

“We really need to start making major changes to end corruption. If I had a child who was killed in Tahrir, then maybe I’d feel completely different.”

Trial must be ‘impeccable’

Just as the news of Mubarak’s resignation came in a terse, barely foreshadowed statement after weeks of his tenacious refusal to give up, so does his Wednesday court date look set to be a last-minute affair.

For months, stories of Mubarak’s failing health have swirled in the media. Many skeptics believed they were intentionally pushed by the ex-president’s camp in an attempt to pave the way for his absence at trial.

First, in April, Mubarak reportedly suffered a heart attack just as his first interrogation began.

He was moved to a hospital near the presidential compound where he was staying in the Sinai Peninsula resort town of Sharm el-Sheikh.

|

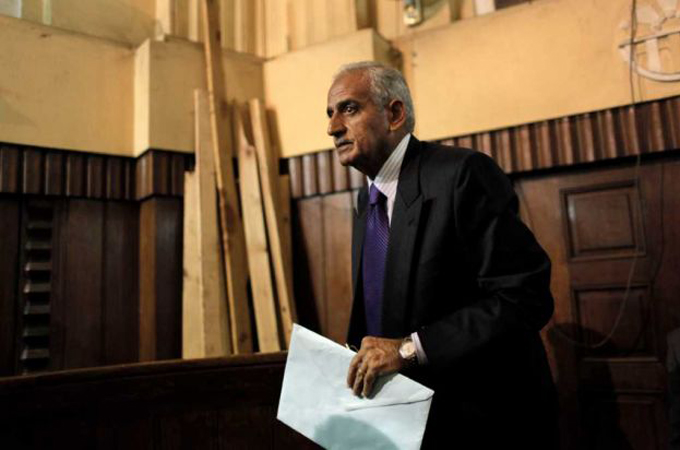

| Judge Ahmed Rifaat, the head of the Cairo Appeals Court, will preside over the trial [AP] |

Then, in June, lawyer Farid el-Deeb confirmed what had long been reported as informed speculation, that Mubarak had cancer – in his stomach – and that his tumours were growing.

In mid-July, as the trial date approached, Deeb claimed Mubarak had gone into a coma, though hospital staff said it was not true.

Many doubt that the military council running the country is eager to see the former commander-in-chief in a cage [a practice used for defendants in Egypt’s justice system].

But the official MENA news agency said on Monday that Mubarak had signed a notification that he was due at trial, and security officials have reportedly been ordered to bring him to the capital.

Heba Morayef, a Cairo-based researcher for Human Rights Watch, said it is crucial that Mubarak’s trial be seen as fair and transparent, and that the case against him be “watertight”.

Recent trials of former regime officials have moved quickly and sometimes gone on despite the defendant’s absence, raising concerns about due process, Morayef said.

The case against Mubarak has also moved disturbingly fast.

“This was a very short investigation against a former head of state by international standards,” she said, adding that she regrets that the trial is limited to only the violence against protesters and does not encompass the rest of Mubarak’s “legacy”.

“From a human-rights perspective, I want this trial to be a precedent, to set the stage for the new Egypt,” she said. “It needs to be impeccable.”

Follow Evan Hill on Twitter: @evanchill