Japan: Lives under pressure

With its nuclear crisis deemed on par with Chernobyl, Japan is dealing with multiple emergencies.

|

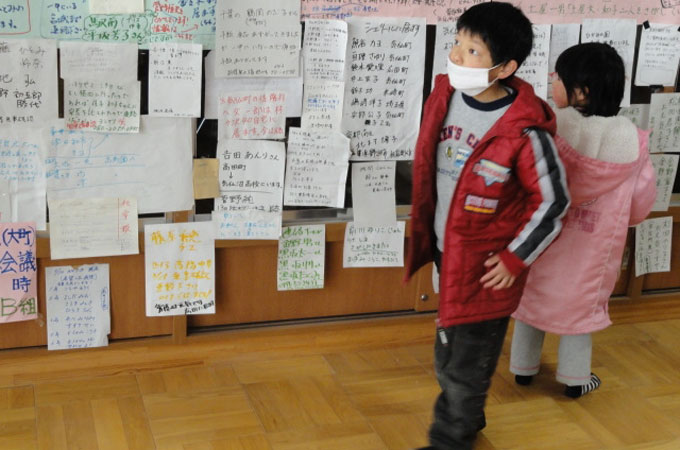

| Children search for names of loved ones at a shelter, hoping missing relatives have left a note [D. Parvaz/Al Jazeera] |

It has been a brutal month for Japan, ever since the twin disaster of a magnitude 9.0 earthquake and powerful tsunami decimated swathes of the country’s northeast coast on March 11.

With over 13,000 confirmed dead and some 14,000 more still missing; with entire communities reduced to rubble; with all the logistical issues that a disaster presents in terms of damage to infrastructure; the Japanese have also had to deal with the increasingly worrying situation at the unstable nuclear plant in Fukushima.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTurtles swimming to extinction in Malaysia as male hatchlings feel heat

Could shipping containers be the answer to Ghana’s housing crisis?

Thousands protest against over-tourism in Spain’s Canary Islands

On Monday, exactly 30 days after the earthquake, another quake hit the region, then another on Monday night, then two more on Tuesday morning.

And then, on Tuesday afternoon, came what seemed to be the worst piece of news yet: Japan’s Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency, a nuclear watchdog, raised the severity level of the crisis at the Daiichi nuclear power plant to 7 – equal to the 1986 disaster at Chernobyl in the former Soviet Union.

For average Japanese, the cumulative stress of the past month has been hard to ignore. New counts of those confirmed dead are posted each day in prefectural offices, where people gather, hoping they won’t see another name they recognise.

For weeks, even those whose homes weren’t destroyed on March 11, have had to deal with shortages of water, electricity, heating oil, petrol and, in some areas, basic food supplies.

And for folks such as Eiji Konno, who raises livestock in the Fukushima prefecture, things are unbearable. Konno, 60, told the Mainichi Daily newspaper that the stress from the earthquake combined with fears of what might come of his farm have caused him to lose 18kg of body mass in a month.

“Sometimes I become overwhelmed by anxiety. It feels as if I’m walking through dark clouds,” he told the newspaper.

Indeed, the need for emotional support services is pronounced, and Kazuo Shimizu, spokesperson for Iwate prefecture’s office of government disaster response, told Al Jazeera that the government is doing what it can to provide such services.

That a demand for something like therapy has even been articulated is remarkable in a culture that traditionally has seen expressing need as equalling weakness. Even modern Japanese psychiatry is based on the notion that Japanese adults are too needy, like children.

A slow seachange

In enduring this trying time and all that it entails, what has become clear is that people – at least more of them than in the past – are willing to speak up to criticise the authorities.

|

Several told Al Jazeera, even less than a week after earthquake, that they did not trust the authorities when they said that radiation levels south of the nuclear plants were low. They were already packing their children and grandparents onto trains, getting them as far away from the nuclear plants as possible.

Other sources said that more people are seeking jobs southern regions of the country in a bid to relocate their families away from the capital, which they feel is too close to Fukushima.

With the nuclear disaster now 100 times worse than initially thought, that anger and mistrust has only increased.

Somehow, prime minister Naoto Kan’s statement on Tuesday that the release of radioactive substances is steadily decreasing isn’t doing much to calm nerves.

Hirotaka Kinoshita, a student at Tokyo’s Temple University, is frustrated. The government and Tokyo Electric Power Co (or TEPCO, which operates the Daiichi plant), he said, are moving “extremely slowly” focusing more on deflecting blame.

The 24-year-old told Al Jazeera that the many in the Kanto area (which includes Tokyo) are trying to pretend that everything is fine.

“In Japan, one will act only if the others act; so when people save electricity, one will try to do the same. This custom has not changed even after the disaster,” said Kinoshita. He points out that a crowd of 12,000 gathered in Tokyo on Sunday to protest the country’s nuclear policy, but that state TV did not cover the rally because they don’t want to draw attention to the discord.

Online, however, “fierce criticism against the government, especially against the prime minister Kan, can be seen in Ustream, Twitter,” he pointed out. “People seem to share their resentment .”

Kinoshita, like many, said he’s worried about the constant aftershocks and the issue of contaminated food, and he doesn’t find the information provided to him by the authorities helpful, adding that he doesn’t really understand the situation but fears the worst – that “the radiation level will soon exceed Chernobyl’s”.

Anger unites generations

Still, even the older generation, less accustomed to speaking up, are doing it in their own way.

One 57-year-old born-and-bred Fukushima prefecture resident- some 58km away from the leaking and overheated nuclear plant – said that he feels he has no faith in the government, calling it “greedy and incompetent and unprepared”.

Even though he openly expressed himself to Al Jazeera, the man said he wanted to remain anonymous because he felt that he’s in “a weak position”, and that only as “one of the nameless” can he say that the government has failed to provide “full disclosure of the information”.

Concerned for the safety of children in the area and resigned to remain there himself, where he will be “a witness of history,” the Koiryama City resident was unflinching in his view of the role authorities have played in the Daiichi crisis.

“This is an accident of governments, corporations and the combined interests of the bureaucracy,” said the man, adding that even though human lives should take priorities, authorities “gave priority to economic gain”.

And in this accident, which involves a nuclear plant he feels ought not have been built, there’s little room for atonement.

“Earthquakes and tsunamis do not forgive,” said the man from Fukushima.

Follow dparvaz on Twitter