Papua: A war with no enemy

Indonesian military keeps tight grip on easternmost province.

|

| A heavy military presence remains in Papua despite the ending of the independence struggle |

The torture scars on the body of 23-year-old Julius Meage are stark reminders of a grim past.

While much of Indonesia has moved on to become a vibrant democracy, the province of Papua in the far east of the archipelago has been left behind.

Suharto, Indonesia’s former strongman president, stepped down 10 years ago, but the legacy of his often harsh rule continues to be felt here.

| In depth |

In June last year, Meage, a resident of the small town of Wamena in the highlands of Papua, was locked up in the house of a local military officer after being accused of stealing the equivalent of $30.

“They pulled out my nails and started to burn my body with a candle. My genitals and tongue were severely burned,” he says.

These claims have never been officially investigated, but are nevertheless fuelling many Papuan’s desire for independence.

Human rights activists like Theo Hesegem have been pressing authorities to have the soldiers arrested, although so far to no avail.

“We have no weapons,” he says. “If the military continues to use violence against us it is clear that we don’t want to be part of Indonesia.”

According to some estimates there are more than 10,000 Indonesian soldiers stationed in what is officially an autonomous province.

They were originally deployed to the region to counter a low level insurgency by the Free Papua Movement (OPM), which waged a campaign for independence in the 1960s and 70s.

Resource rich

|

| Despite being rich in resources, Papua remains Indonesia’s poorest province |

The OPM have long since put down their arms, but dreams of independence live on among the Papuan people.

Papua only became part of Indonesia in 1969 after the former Dutch colony – under supervision of the United Nations – organised a referendum that is widely seen as a sham.

In 2001, in an effort to convince Papuans to stay a part of Indonesia, the government in Jakarta promised extensive self rule for the resource-rich province.

Profits from the region’s abundant gold, copper and timber reserves used to end up in Jakarta, but under the new deal Papuans were promised a greater slice of the pie.

Seven years later few Papuans have seen any improvement.

On paper, more money has been sent from the central government but most of it has vanished in bureaucratic channels or has been stolen by local officials.

Barnabas Suebu, Papua’s first directly elected governor, has promised to clean up the system, saying he wants to make sure that the money does indeed reach the province’s two million inhabitants.

But, he says, it is a process that will take time – “at least another five to ten years”. Only then will Papuans start to feel the benefit.

In the meantime many Papuans have lost their patience. Autonomy, they say, has failed them – money alone is not enough; they also need to see justice.

Welfare

|

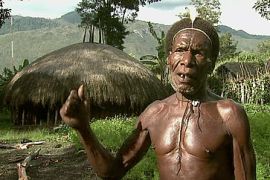

| Tribal chief Husit Wetipo says his people have seen no benefit from autonomy |

Suebu, the Papuan governor, says the soldiers must change their approach.

“There is no war going on here, so the military should use a more persuasive approach improving the welfare of the people,” he told Al Jazeera.

But in the Baliem Valley in the central highlands of Papua, welfare has a very abstract meaning.

Just two years ago, 55 people in the remote Yohukimo district died of starvation.

We could only reach the area by foot after a major landslide cut off the only road.

Here life continues as it has done for centuries – women working their potato fields, men still wearing the traditional ‘koteka’, penis sheath.

Until just 60 years ago the people in the Baliem Valley had had no contact with the outside world.

Husit Wetipo, the local tribal chief, who lives in a typical traditional Papuan hut called a “honay”, told us he has lost all hope.

“We know a lot of money is coming in but we don’t receive anything,” he says. “The government treats us as mad people because we are still not wearing any clothes.”

Wetipo dreams of a free Papua and a better life for his people.

Indonesia meanwhile continues to pursue its hearts and minds policy – and so far, it seems, they are winning neither.