Red tape battle for China migrants

Outdated ‘hokou’ registration system fails to keep pace with changing China.

|

| Fix-it man Ding Jia Xing moved to Beijing a decade ago in search of a better life |

Ding Jia Xing is one of tens of thousands of fix-it men, scraping a living in Beijing.

Every day he works out the kinks – charging the equivalent of a few cents for each job.

Ding is from China‘s far north and travelled over a thousand kilometres to the Chinese capital in search of a better life.

“I came to Beijing in 1993, with a few other people from my farm town,” he says.

|

| Millions of migrant workers find they are unable to escape the ties of the hokou system |

“I did all sorts of things when I first arrived. I worked in restaurants, I delivered boxed lunches.”

He has been in Beijing for over a decade, but as far as the city is concerned, Ding Jia Xing does not exist.

Ding does not hold something called a hukou – China’s system of registration and identification.

It may not sound like a big deal, but the hukou is a social class system. It determines where you receive services – such as health care and education – and it is generally immovable from the city your family comes from.

A relic of the early days of communism in China when party officials organized work units for collective farming and production, the hukou determines a person’s occupation and place of residence.

And 50 years after its inception, the hukou has seen little change.

|

The hukou system historically has been a way in which to contain people” Russell Leigh Moses, |

“The hukou system historically has been a way in which to contain people,” says Russell Leigh Moses, an expert on Chinese social affairs.

What the hukou does, he says, is to “contain them from travelling, contain them from switching jobs, and essentially to tell people this is your allotted lot and space in life.”

Ding Jia Xing simply lost his social safety net when he moved to Beijing.

He had to bargain whether moving to Beijing for better wages would outweigh the costs of losing government health care and other services.

And since the birth of his daughter, he has had to consider the fact that the government’s guarantee of free education, might not apply to her.

He has managed to secure her a place at a school, and says that while he used to have to pay tuition and textbook fees, that has since been waived by the government.

Education bar

|

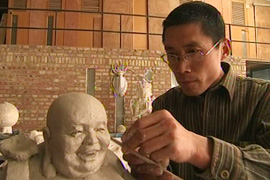

| Artist Li Xue Jun is one of an estimated 150 million internal migrants |

Still, that is not always the case and the cost of schooling bars half of all migrant children from primary education.

Artist Li Xue Jun lives at the opposite end of the economic scale.

He is a successful sculptor, part of China‘s emerging and lucrative contemporary art movement.

Through art, Li says, is freedom. But even Li is bounded by problems posed by the hukou.

An out-of-towner, he faces trouble buying real estate.

“If I want to buy a house here in the future, or if my parents want to join me here, there will be problems,” he says.

“I’m an artist. I’m independent. So I guess I’ll have to solve these problems on my own.”

Li doesn’t think too far into the future, but he tells us that one day his child will face the same hukou issues — because the hukou is not based on the place of your birth, but is inherited.

And for that reason, the hukou defines issues of finance, citizenship, and identity for all Chinese.

Official estimates place China’s migrant population at 150 million, or about 10 per cent of the population.

Uncertainty

|

| The children of migrants face similar problems because the hukou is inherited |

It is the largest movement of people in the history of mankind, and is happening at the fastest rate.

While many people obtain temporary residence permits in the cities, changing a hukou is next to impossible.

And while the government recognises the need to update the system, change might take years.

It would require consensus at the top and, while policy makers have raised the issue intermittently, it has never made it to the national agenda.

Certainly the hukou issue is not the most pressing problem faced by a rapidly changing China. Most people simply get on with their lives without thinking too much about their hukou, adjusting to the inconveniences it might create.

But there is always an element of uncertainty hanging over those who live beyond their registered hukou.

In the past, many local officials have enforced the hukou as a means to control the poorest strata and, as Russell Leigh Moses warns, that could spell out problems in the future.

“If you have economic downturn, or if you have inflation going out of control – then individuals might be further pressed economically and want the state to intervene and help them out.”

With inflation currently running at an 11-year high, this may well mean the government will need to address and resolve the hukou issue sooner than they expected.