Eastwood shines light on Iwo Jima

Sixty years on after the battle, Letters From Iwo Jima tells the Japanese side of the story.

|

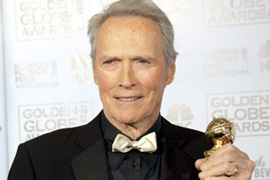

| Clint Eastwood’s film won the Golden Globe’s best foreign movie award [AP] |

For more than 60 years, the bloody battle for Iwo Jima in the waning days of World War Two has always been told from the American side of the equation.

But in early December, Hollywood icon Clint Eastwood, broke the barrier by telling the story of some of the fiercest fighting in the Pacific from the point of view of the losers – the Japanese, and in their own language.

Initially, Eastwood only planned to make one movie, based on the best selling book titled Flags of our Fathers, which was written by James Bradley and told the story of his father, John, and five other US soldiers who raised the flag atop Mount Suribachi.

But once on the island, Eastwood realised that he would only be telling half of the story.

“It is not about winning or losing, but mostly about the interrupted lives of young people, and losing their lives before their prime,” the director told reporters at a press conference in Tokyo. “These men deserve to be seen and heard from.

“Those soldiers deserve a certain amount of respect.”

Golden Globe recognition

The Hollywood Foreign Press Association thought so to.

On January 16, Eastwood’s Letters From Iwo Jima received the best foreign language film award at the 64th Golden Globes in Los Angeles, narrowly beating Mel Gibson’s classic, Apocolypto.

| It was a very moving experience, to walk around Iwo Jima |

The filmmaking process was in itself a feat because Eastwood, known for his spaghetti Westerns had to first convince Japanese war veterans that the story would hold true to their version of events.

With the blessing of Japanese veterans’ groups, who consider the 12-square-km island to be sacred ground because the bodies of many of their comrades could never be recovered, Eastwood cast Ken Watanabe as General Tadamichi Kuribayashi and set about filming Letters.

“It was a very moving experience, to walk around Iwo Jima,” Eastwood said.

Eastwood also wanted the movies to be tribute to the thousands who died in what one US veteran recalls as a “sulphurous, crater-filled hellhole”.

The US commanders planning the invasion expected Japanese resistance to end within four days. Instead, it took the marines nearly four weeks – and 28,000 casualties, including 6,821 dead – before the stubborn defenders were overcome.

A mere 1,023 of the 21,000 Japanese defenders were captured alive.

Accolades

Letters, released just before Christmas in the US, has already surpassed expectations by being selected as the best movie of the year by the Los Angeles Film Critics’ Association.

It has also been ranked in the top 10 titles of the year by the American Film Institute and, the Golden Globe nod is sure to make it a strong contender for the Academy Award Oscars on February 25.

|

| Japanese bunker built around fuselage of crashed bomber |

It took more than Y200 million ($935,000) on its opening day in Japan and is eventually expected to earn some Y5 billion ($23.4 million).

With the end of World War Two, Iwo Jima returned to being an unimportant volcanic rock in the Pacific, 1,250 km from Tokyo and on the way to nowhere.

Former residents did not return because of the unexploded ordinance still littering the battlefield and the only presence was the militaries of Japan and the United States, as well as occasional parties of returning veterans.

Museum

In a small museum close to the Maritime Self-Defence Force’s runway, a rusted Japanese heavy machine-gun stands on its tripod beside the skeleton of a flame-thrower’s rig that was only found in the low jungle that covers much of the island earlier this month.

A helmet with entry and exit holes is beside a warped record, scorched documents, china bowls and corroded bayonets and bugles.

Beyond the perimeter of the air base, much of the rest of the island is similarly a museum. The northeast of the tear-shaped island was where the remnants of the Imperial Japanese Army made their last stand, fighting from well-concealed bunkers that resisted artillery and naval bombardment and required the US marines to take them one by one.

|

| Inside Imuka-gou hospital cave |

Tenzan Cave was the final foothold for organised Japanese resistance and the complex incorporated two large-calibre naval guns. A few hundred metres to the north – a distance traversed in minutes today but in days and at huge cost 60 years ago – is the Japanese navy’s underground headquarters and the Imuka-gou hospital cave.

The entrance to the cave is overgrown and a clutch of bottles of offerings of sake and water stand just inside the mouth. Ceramic bowls, cannisters and fragments of glass and metal stand against one wall.

Mount Suribachi

The cave was only opened in 1984; it contained the mummified remains of 54 Japanese service personnel.

Past a monument to the 82 residents of the island who died fighting alongside the military during the invasion are the remains of half-a-dozen reinforced concrete ships that were towed to the island to be sunk off Chidoriga Beach and provide an artificial breakwater.

Inland, the nose of a crashed Japanese bomber has been encased in concrete and served as a strongpoint for a machine gunner.

But it is Suribachi that will forever be the symbol of this particular battle.

The mountain was riddled with 20 km of underground tunnels with 1,500 well-concealed firing points.

The Japanese plan was not to fire on the American forces as they came ashore but to wait for them to lay completely exposed on the beach below and to the east.

Memories of battle

Grainy television images show the first marines jogging ashore unopposed and officers indicating with flags the route for open-topped Jeeps. Precisely one hour after the landing began, the Japanese defenders opened fire from positions that the American commanders assumed had been destroyed in the preliminary three-day barrage. Gunfire raked the exposed beaches and 2,420 marines never even got off the grey, volcanic sand.

| When I saw the island from the plane for the first time, I remembered what it had been like when we had been filming the battle scenes earlier and I only stopped crying when we finally landed |

The story of the raising of the flag on the top of Suribachi is a legend within the Marine Corps. The shot that Rosenthal took was later turned into the monument to the regiment in Washington, even though it was not the first flag to go up that morning.

It had taken four days to get the flag flying and there were weeks of fierce, often hand-to-hand fighting ahead that would claim three of the men in Rosenthal’s picture. The fall of Suribachi did, however, make the eventual outcome inevitable.

“The role I played was very hard,” Watanabe said in an interview recently in Tokyo.

“When I saw the island from the plane for the first time, I remembered what it had been like when we had been filming the battle scenes earlier and I only stopped crying when we finally landed.

“It has left an amazing impression on me. It’s a terribly sad place.”

General Kuribayshi

After reading correspondence from General Kuribayashi on the island to his family on the mainland, Watanabe made numerous suggestions to Eastwood and the script writers in order to better capture the emotions of the military commander. The result, he believes, shows the general to have been thinking of his family and steeled to fight despite a good understanding of his adversaries garnered as a military attache in the US in the 1920s.

“Eastwood wanted to show the struggles of this man,” Watanabe says. “It is not just that he is a military man, but through the lens we see how men in these situations thought, functioned and lived.”

That he did his duty is unquestioned; the US forces were substantially delayed even though Japan could no longer win the wider war.

General Kuribayahsi’s remains have never been found and it is not known whether he died in action or by his own hand. The present commander of the island, Captain Tomonori Kudo, has a poster of Letters From Iwo Jima posted just outside his office.