Fear haunts Rwanda’s acquitted

A return to normality proves a challenge for those cleared.

|

| Critics say the ICTR has ignored the fate of those it acquitted |

Since its inception in 1994 to try persons responsible for genocide in Rwanda, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) has indicted 28 people and acquitted five.

But for those acquitted, a return to normality and their homes has proven to be a greater challenge than the trial.

In the hushed surrounds of a library in the northern Tanzanian town of Arusha, Emmanuel Bagambiki, a Rwandan Hutu who is one of those acquitted, receives written confirmation that Belgium will review his failed visa application.

“It is small progress,” says the 59-year-old former senior government official.

In 2004, the ICTR found Bagambiki not guilty of orchestrating the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

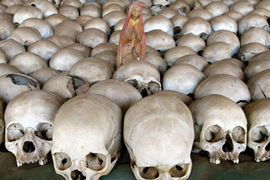

Almost 800,000 people, mostly ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus, were massacred in a 100-day killing frenzy.

The ICTR’s verdict provoked widespread protests in his province of Cyangougou in southwest Rwanda and prompted the Rwandan government to issue an international warrant for his arrest.

Fear of repatriation

For three years Bagambiki has remained confined to the compound of the ICTR by day and a safe-house by night.

|

| Almost 800,000 people were systematically massacred in 100 days [AP] |

Now he is seeking domicile in a number of French-speaking countries including Belgium where his wife and three daughters, who have been granted Belgian nationality, live.

He says he fears for his life should he return to Rwanda.

So far, no member of the international community has stepped forward to offer Bagambiki a home.

Bagambiki told Al Jazeera: “It has been like another prison … we don’t have [the] impression that we have really been acquitted. It is as if our names remain associated with the genocide.”

Court criticised

In its 10-year history the ICTR has been criticised for its bureaucracy and spiralling costs, which now total more than $1bn.

While tribunal officials point to the 28 convictions sealed by the court, critics argue that it overlooked the fate of those acquitted.

“A cynic might think no acquittals were expected from this court,” says one senior tribunal official on the condition of anonymity.

However, Roland Ammoussouga, the senior legal adviser and spokesperson for the ICTR, denies the court was established to simply roll out convictions.

He told Al Jazeera: “International justice never works on the assumption that all are guilty.”

Ammoussouga points to the war crimes tribunal for the former Yugoslavia based in The Hague on which the ICTR is modelled.

“There the acquitted return to the Balkans as heroes,” he says.

However, he concedes, “the ICTR thought it would be easier to find a host country” for those acquitted of Rwandan genocide.

Seeking extradition

But Martin Ngoga, Rwanda‘s prosecutor general, told Al Jazeera his government was not happy with Bagambiki’s acquittal and that the accusations against him are still considered open.

The Rwanda government says the ICTR refused to try Bagambiki on what it says are additional charges of rape and complicity to rape.

He said: “We believe the trial was not properly conducted. The trial was under way and the chamber did not want to get bogged down.”

|

We believe the trial was not properly conducted. The trial was underway and the chamber did not want to get bogged down |

He added that the Rwandan government would move to extradite Bagambiki from any future host country and put him on trial in the capital, Kigali.

Since his arrest in 1998 in Togo, where he and his family had sought refuge, Bagambiki has fought to clear his name and start a new life outside Africa, where he says his security is now “compromised”.

Bagambiki remains diplomatic about the impasse over his future. “We don’t see why we should be undesirable, why we should be persona non grata in any country.”

France has offered domicile to two others acquitted in the trials. This gives Bagambiki hope.

Political counterweights

But Vincent Lurquin, Bagambiki’s Brussels-based lawyer, believes political constraints may prove daunting.

Lurquin has spent three years fighting Belgium‘s rejection of his client’s visa application.

Lurquin believes the risk of jeopardising relations with the administration of Paul Kagame, the president of Rwanda, is deterring Belgium, like others, from opening its doors to Bagambiki.

Others within the ICTR are more forthright.

The tribunal official who spoke on condition of anonymity said: “It is a political issue. It maybe politically damaging to take on people associated with the genocide if they have no particular connection to your country.”

Nevertheless, the ICTR insists it is working hard to find a solution. Earlier this year Adama Dieng, the tribunal’s registrar, tasked with finding the acquitted a home, travelled to the UN Security Council in New York to persuade the international community to help the three men.

So far, his trip has not borne any fruits.

As Bagambiki returns to the safe-house, he asks “if you are acquitted, you are acquitted, so why continue to sanction us?”

For the time being, he has no answers.