Executed, then acquitted: Fair trial concerns plague Pakistan

Pakistan has executed 496 since 2014. Rights groups say serious fair trial concerns risk innocent people being killed.

Islamabad, Pakistan – On a brisk February night in the village of Ranjhay Khan in central Pakistan, Ghulam Qadir received a phone call: “Come and meet us,” the voice said, “and we will resolve all of this.”

The 37-year-old television repairman had been trying for months to get justice for his young daughter, Salma.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRecord number of people executed for drug offences in 2023

Executions in Iran hit 8-year high in 2023

Australian writer Yang Hengjun sentenced to death on China spy charges

Months earlier, she had been kidnapped at gunpoint, her family said, and was only returned after Qadir managed to get an army officer, a customer at his small electrical workshop, to intervene on his behalf.

Salma said she had been kidnapped and raped by a man called Akmal.

Qadir had been trying to get the police to register a case but to no avail.

Then, a phone call in the dead of night.

Qadir went to attempt to negotiate a settlement with Akmal and his father, Abdul Qadir, both members of a rival clan.

It was a trap, family members claimed. Qadir was tied up and beaten as Akmal and Abdul Qadir demanded that he stop approaching the authorities to try and have them arrested.

Soon, matters escalated, as Qadir’s family members arrived at the scene. Shots were fired.

When the dust settled, three bodies lay on the floor: Akmal, Abdul Qadir and Salma, Ghulam Qadir’s daughter.

Police arrested Qadir, his brother Ghulam Sarwar, and six others on murder charges. The two brothers were tried and sentenced to death in May 2005, the others were acquitted for lack of evidence.

For 10 years, the Ghulam brothers waited on death row, insisting on their innocence, as their appeals made their way through Pakistan’s labyrinthine justice system.

Finally, on October 6, 2016, the Supreme Court declared that there had been a miscarriage of justice and that there was insufficient evidence to convict the brothers. They were acquitted, and free to go.

But the Ghulam brothers had already been hanged on October 13, 2015, almost exactly a year earlier.

4,688 people on death row

Since Pakistan lifted a moratorium on executions in late 2014, following an attack on a Peshawar school that killed more than 140 schoolchildren, the country has become one of the world’s most prolific executioners.

At least 496 prisoners have been executed since then, according to data collected by the Justice Project Pakistan legal aid organisation.

Meanwhile, the country’s death row population continues to swell, with at least 4,688 people awaiting execution.

Based on that data, every fourth person on death row in the world is a Pakistani. Every eighth person to be executed is killed in Pakistan.

There is resistance to the idea of fair trial in Pakistan, particularly for sensitive issues like corruption, terrorism and other serious crimes. This has grown in the age of social media.

The country’s criminal justice system has long been challenged by several issues, from an excess of cases to insufficiently trained prosecutors, lawyers say, raising significant fair trial concerns.

“When the Peshawar school attack happened, they seemed to be keen to just execute everyone, legally or illegally,” said Muhammad Aslam, 48, the Ghulam brothers’ nephew. “There is no justice in this country for the poor – maybe there is for the rich.”

Justice Project Pakistan (JPP) has been advocating for years for the re-imposition of the moratorium on executions to allow for reforms to ensure that innocent people do not find their way on to death row.

“There are very deep structural problems in Pakistan’s criminal justice system,” said Sarah Belal, JPP director. “Anyone who works within it, victims, lawyers, judges, prosecutors … all the way to the Supreme Court knows that something needs to be done.”

She said the problems begin right from the moment a suspect is arrested.

![Sabir Masih, from a family of executioners, claims to have executed roughly 250 people [Asad Hashim/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/5267d1153b99437392c30678d235f3e7_18.jpeg)

“Torture by the police is used systemically and it is endemic. Until we focus on that, we can have no sound convictions.”

Research on police brutality in Pakistan shows the widespread use of torture to extract confessions from suspects, and an over-reliance on confessions as opposed to other forms of evidence in criminal cases.

The entire system, JPP explained, is broken.

“You have defendants with no means forced to get public defenders, and then you get defence lawyers who never visit the prisons or gather any evidence,” Belal says.

“You have a state operating on 1940s principles of who is allowed [to visit prisoners], it’s in a complete shambles. How can you have due process when you have such problems?”

Reema Omer, a legal adviser at the Switzerland-based International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), and herself a lawyer with years of experience within Pakistan’s justice system, said the amplification of public anger is concerning.

READ MORE: Blasphemy in Pakistan – Anatomy of a lynching

“I think there is resistance to the idea of fair trial in Pakistan, particularly for sensitive issues like corruption, terrorism and other serious crimes,” she told Al Jazeera. “This has grown in the age of social media, where public outrage has reversed the premise of a fair trial – that of the presumption of innocence.”

Omer also pointed out the slowness of the system, which can lead to innocent people spending years on death row.

“It takes more than 10 years for people wrongly convicted and sentenced to death to eventually be exonerated,” she says.

Blasphemy among crimes that carry death penalty

The number of people on death row in Pakistan is one of the highest in the world, and it keeps growing, partly because of the wide array of crimes for which capital punishment is prescribed.

Pakistanis may be sentencedto death for up to 27 crimes, including murder, drug-related offences, hijacking, rape and blasphemy.

![Salman Taseer, right, was killed in 2011 for supporting Asia Bibi, left [File: EPA/Governor House handout]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/e24bb5dfcf4c4490a2d97ebaf126bac7_19.jpeg)

Pakistan sentenced more than 200 people to death last year, according to Amnesty International. Last year, 87 percent of all recorded executions worldwide took place in Pakistan, where more than 60 people were killed, Saudi Arabia (146), Iraq (125) and Iran (507).

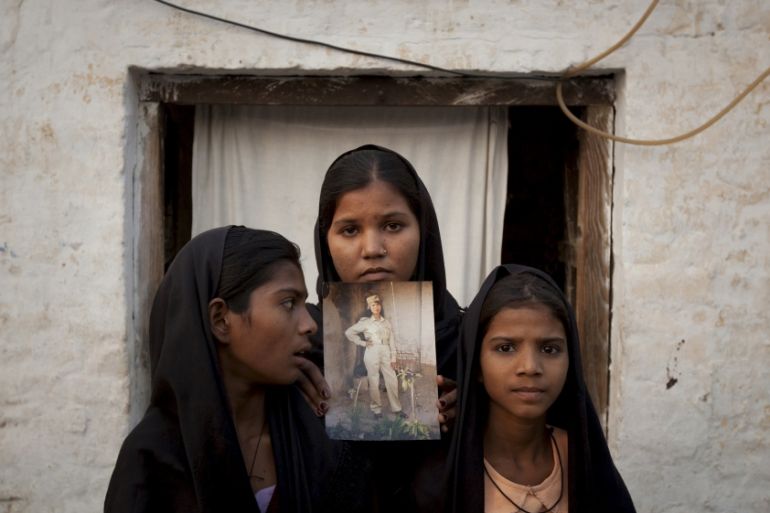

Asia Bibi, a young Christian woman from the Pakistani village of Ittan Wali, is on death row. In 2009, Bibi was tried and convicted for having committed blasphemy, after an argument with two Muslim women who objected to her drinking from the same water vessel as them.

Bibi’s trial, which court documents show is riddled with legal inconsistencies, has become iconic of the problems in Pakistan’s justice system.

In 2011, then-Punjab Governor Salman Taseer was murdered by his own bodyguard for championing Bibi’s case and calling for reforms to Pakistan’s strict blasphemy laws. Then, Federal Minister Shahbaz Bhatti, who also advocated for Bibi, was killed weeks later.

On death row for eight years, Bibi’s appeals continue to wind their way through Pakistan’s system. On Monday, the Supreme Court closed arguments in her final appeal and reserved its verdict in the case.

Far-right groups such as the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) have threatened to hold countrywide protests unless Bibi is hanged, demanding that she be made the first person Pakistan has ever executed for “blasphemy”.

‘Someone else should get justice’

Back in Ranjhay Khan, Aslam, the Ghulam brothers’ nephew, recalls the last time he met his uncles in jail, hours before their execution.

“We were crying, all of us. What else could we do?” he said.

At least 50 people made the hours-long journey to the Bahawalpur jail to meet them for the last time, he said.

“That’s how much respect they had in our village.

“They cannot come back … We just want that no poor person is ever trapped like this again. At least someone else should get justice.”

For Aslam, the death penalty is a justified punishment for certain types of crimes, particularly murder. He wondered, however, if it can ever be applied with confidence given the state of Pakistan’s justice system.

“Under Islamic law, a murderer should be killed. But when you cannot guarantee justice, when you are not even able to keep track of those who you have executed and on what basis, then how can you have the death penalty?” he asked.

“Those that are killed, they cannot be returned to life. The law has acquitted them – but they are gone.”

Follow Asad Hashim on Twitter: @asadhashim