Wind in the willows: A cricket bat paradise

Behind the towering willows, Kashmir’s cricket bat industry is a living, breathing symbol of the conflict.

The old road from Srinagar, the capital of Indian-administered Kashmir, to the town of Sangam, enroute to the tourist haven of Pehelgahm, takes you from the melancholic to the spectacular.

The road is flanked by run-down two-story thatched structures, dusty granite stone factories and an army garrison surrounded by poorly camouflaged bunkers, stray dogs and dirty footpaths.

But the muck is a prelude to a green corridor of hanging trees, soggy poppy fields, freshly tilled saffron gardens and towering snowcapped mountains beyond the horizon of the Pampor highway to Kashmir’s south.

“These are Russians Poplars; they are thinner than the native Poplars … God knows how they got here,” my companion for the day tells me, pointing up at the tall trees, little pockets of sunshine filtering through the leaves.

Here, in Sangam, some 40km from Srinagar, beneath the shade of a towering Kashmiri willow and lines of Kikar trees, is a cricket bat paradise.

Beyond the industrial grime of the capital and the pockets of sludge and environmentally unfriendly filth that is the business of any city’s periphery, the main thoroughfare leads you to a calmer repository … of cricket bat factories, sports shops and billboards bearing the insignia of the biggest names in the cricketing world.

It is not exactly Kashmir’s rabbit hole – a faraway place of Hobbit miracle workers, unhindered by the scars of a bloody conflict, sculpting cricket bats night and day as a token of love for sports enthusiasts far away – but it is, nevertheless, quite impressive.

|

|

Said to employ an estimated 10,000 Kashmiris, the industry adds an estimated 500,000 bats to the Indian and international markets each year. Long handles, short handles, Mongoose bats, autographed bats, half-size short handle bats – thousands of boys, girls, men and women wrap their palms around the handle of a willow carved from the trees of the valley.

Kashmiri cricket bats are made from both willow, imported by the British to service their energy needs, and the native, dervish-looking Poplar trees.

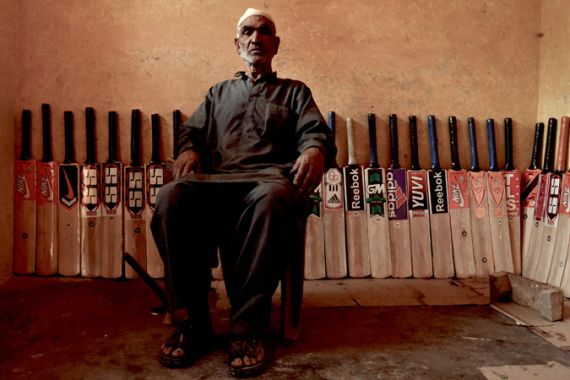

Behind the façade of shop windows bearing lines of neatly arranged bats, emblazoned with MRF, Reebok, GM, Adidas stickers on the face, splice and spine, is a world of drying planks of stacked Kashmir willow, unfixed handles imported from Punjab and generator-powered machinery designed to cut planks into a basic cricket blade.

Cricket and conflict

Some say it has been the best summer since 2007.

“This year has been especially good; firstly the calm in the valley and secondly with India winning the World Cup, this has spiralled sales here and across India,” Riyaz Ahmed Ganai tells me in his father’s cricket bat factory, Topline Sports. in Mirzapora.

Ganai says that the rise of the Indian Premier League (IPL) has done much to boost sales and even forced them to make new types of cricket bats to suit the new game. When India won the World Cup in March, the demand for bats in India might have risen exponentially, he says, but in the valley the effect was short-lived.

“Sales did increase and people were excited, but if Pakistan had won the World Cup the affect on sales and the interest in the game would have lasted longer,” he smiles.

“My father told me that when Pakistan won the world cup in 1992, sales were so good, we even sold the bad planks as cricket bats,” Ganai says, picking up a dark, soggy plank whose dreams of smashing cricket balls were long over.

“Now that has never happened since.”

But like everything else in Kashmir, the fortunes of the cricket bat industry are dependent upon a larger political game. The industry, which produces bats ranging in price from Rs 50 ($1.10) to Rs 2,000 ($50), is a living, breathing symbol of the more than two decade old conflict.

It is unsurprising then to hear that the fortunes of both India and Pakistan on the cricket field energise the game, invigorate or diminish sales and influence the scope of shipments to the rest of the sub-continent.

Ganai’s father’s factory has had to ride out the volatile political conflict, which as well as costing between 50,000 and 70,000 lives, has upset the rhythm of life in the valley.

“Over the years, there have been so many factors that have cost the business. These include the turmoil but also the earthquake in 2005 and 26/11 [the 2008 terrorist attack in Mumbai]. Events in Pakistan affect us too,” he says.

A three-month lockdown in 2010 – in response to demonstrations that led to an intermittent curfew, indiscriminate crackdowns and culminated in the deaths of more than 115 teenagers – saw the entire industry shut down for the summer.

Ghulam Mohammed Dar, from Neelam Sports in Sangam, says his business sells around 5,000 to 7,000 bats every year. It operates on the principal of ‘just in time’, or Kanban for the purists, and their policy, like that of most factories dealing with products susceptible to seasonal variations in demand, is not to keep extra stock.

|

So, last year, when the business was closed during the crucial summer months, Dar had no bats to send out when the time came to deliver.

“No workers pitched for work and with everything on lockdown, we could not manufacture bats as per usual,” he says. “As a result we lost 50 to 70 per cent of sales in 2010.”

Ganai agrees that the events of 2010 hit the family business hard. “So we had all these bats – thousands of them waiting on order – and we could not send them,” he says.

It was only when the Chinar trees shed their leaves in October and November that they were able to get back to work.

“Usually in summer … about 2,000 bats a month are sent to India. But with the lockdown, we had to send some 10,000 bats in October and November alone,” Ganai explains.

“But so far it has been good a year,” he continues. “All we need is for Pakistan to win every series, and we’d do well,” he laughs.

It has been some time since we entered Ganai’s factory unannounced, interrupting him as he filed the shoulders of a newly cut bat, and he gestures that he needs to go back to work, to toasting that wood … for the rest of us.