Vaccine hesitancy is not a ‘Muslim problem’

But it does seem to be a European one.

Hostility towards vaccination programmes is often portrayed as a problem that predominately afflicts Muslim-majority societies. Vaccine hesitancy is, however, a major public health issue in Europe and recent research shows it is driven by the same anti-establishment sentiment that led to a surge in support for populist political movements.

Safe and easily administered vaccines have vastly reduced the prevalence of once-common and devastating diseases. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that they prevent 2 to 3 million deaths each year.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsDeadly Sahel heatwave caused by ‘human-induced’ climate change: Study

Woman, seeking loan, wheels corpse into Brazilian bank

UK set to ban tobacco sales for a ‘smoke-free’ generation. Will it work?

However, a further 1.5 million deaths could be avoided if vaccine coverage was increased.

Historically, the biggest obstacle to increasing coverage was limited access to vaccines in low-income countries. In the past two decades, global health actors, such as the WHO and the Gates Foundation, have spent billions of dollars improving vaccine supply to previously under-served populations.

Now, the major obstacle to raising immunisation rates has become related to demand.

|

|

The Muslim world is frequently characterised as the epicentre of vaccine hesitancy. This view is informed by several high-profile incidents related to polio eradication efforts, most notably a boycott in northern Nigeria in 2003 and sporadic attacks on vaccinators in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan over the past decade.

In the West, perhaps predictably, these episodes have been explained in terms that evoke Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations thesis.

New York Times journalist Donald McNeil, for example, caricatured polio eradication efforts in Pakistan as “a holy war – … radical Islam versus those it considers Crusaders … Western science versus Eastern faith”.

However, not all “radical” Muslims are hostile to polio vaccination campaigns, let alone all Muslims. The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS) group allowed polio vaccinators to operate in areas of Syria under their control, and the Afghan Taliban has been at times supportive of eradication initiatives.

Hostility and suspicion towards polio campaigns in northern Nigeria and north-west Pakistan must be understood in the context of broader political conflicts between marginalised groups – Muslims and Pashtuns respectively – and the federal state and their Western allies.

It is unsurprising that vaccination campaigns, which are funded, organised and undertaken by actors associated with antagonistic postcolonial states and “the West”, are interpreted by marginalised communities as projects to exert control and are therefore met with hostility.

For example, the graph above shows how polio prevalence in Pakistan correlated with the frequency of US drone attacks between 2004 and 2011. Militants suspected that polio vaccination campaigns were a smokescreen for intelligence-gathering operations, and were therefore reluctant to grant them access to areas under their control.

The pattern breaks down after 2011, when it was revealed that the CIA used a fake vaccination campaign in an attempt to acquire DNA from Osama bin Laden’s relatives. This resulted in a violent boycott in Waziristan, north-west Pakistan.

Apart from these two cases, the Muslim world by far does not lead in vaccine hesitancy. In 2015, researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine carried out surveys in 69 countries which showed that, in fact, Europe has the highest levels of vaccination refusals in the world.

Polio, which is passed on through the faeces of infected people, is no longer a public health issue in Europe. To understand vaccine hesitancy in high-income countries, it is instructive to look at an airborne disease like measles.

In the past few years, coverage has fallen due to unsubstantiated concerns that the Measles, Mumps, Rubella vaccine causes autism. Concurrently, measles has boomed in Europe: from 5,273 cases in 2016, to 23,927 cases in 2017, to 82,596 cases last year – the highest number this century.

Moreover, there is a clear link between increased vaccine hesitancy and the rise of anti-establishment movements that have disturbed the dominance of centre-left and centre-right political parties.

Western European countries with the highest prevalence of measles are Greece, France, and Italy. SYRIZA won power in Greece in 2015, in 2017 Marine Le Pen came in second in the French presidential elections, and the Five Star Movement and the League have governed Italy since last year.

In Italy, the Five Star Movement are vocal critics of the MMR vaccine and, in August, the newly-elected Italian upper house passed legislation to remove a law that made it compulsory for children to be vaccinated before enrolling in state schools. Similarly, in Greece, the SYRIZA-led government have threatened to revoke a law that makes vaccinations obligatory for children. In France, Le Pen’s party the RassemblementNational, have raised questions about vaccine safety.

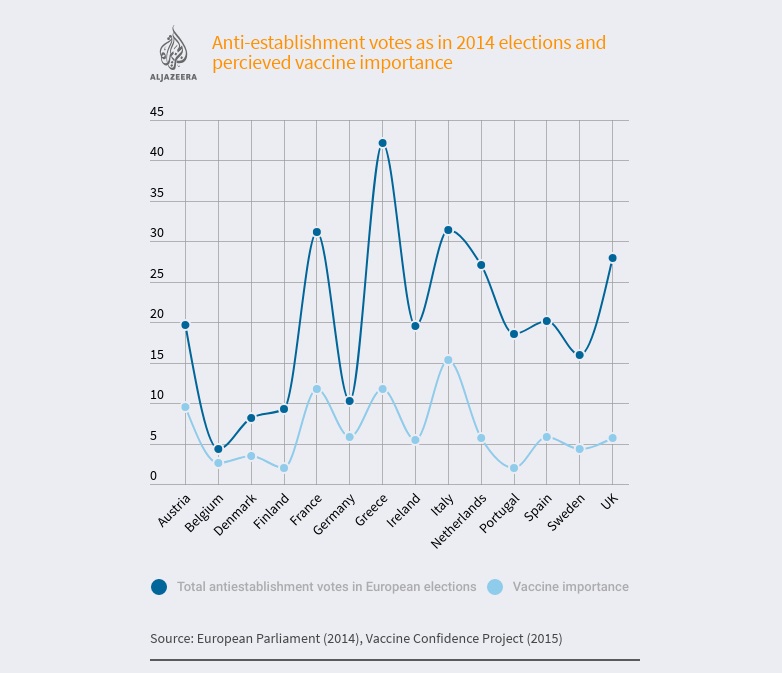

The graph above is based on a study recently published in the European Journal of Public Health. It shows that countries in which anti-establishment parties – ie, those not in centre-left or centre-right groupings – received a high proportion of the vote in the 2014 European Parliament elections also tended to have a large percentage of people who didn’t think that vaccines were important in 2015.

Populist political movements do not share an ideology. They can be right-wing (Rassemblement National), left-wing (SYRIZA), or reject the right-left division altogether (Five Star Movement). What unites them is their willingness to take advantage of widespread antagonism towards “the establishment”, a pejorative term that usually encompasses the political elite (traditional politicians and parties), economic elite (bankers, big business and the rich), and media elite (mainstream media companies).

Concerns about MMR can be seen as an example of “technological populism”, a term coined by the sociologist Harry Collins to refer to extreme and uninformed scepticism towards scientific expertise. Technological populism is driven by similar dynamics to political populism: profound distrust of elite and experts, in this case, pharmaceutical companies, public health authorities, and doctors.

On the face of it, marginalised Muslims in northern Nigeria or northwest Pakistan and disaffected Greek, Italian and French voters do not have much in common. They are, however, united by their reluctance to follow the advice of the state and medical professionals to vaccinate their children.

Their concerns cannot simply be dismissed as zealotry or irrationality. These communities have reasons to distrust political elites, which inevitably has negative effects on other aspects of social life including public health.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.