In defence of science: Making facts great again

We must not let rhetoric or vested interests divert us from what we know is the right course of action.

From across the Atlantic, the European scientific community is watching warily as our American colleagues endure increasingly politicised attacks on their work and on the very foundation of evidence-based science.

President Donald Trump‘s decision earlier this month to withdraw the United States from the historic Paris Agreement on Climate Change – a decision condemned by heads of state, businesses, mayors and ordinary people in the US and the world over – epitomised this contempt for the facts from some within the political sphere.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAfter the Hurricane

World’s coral reefs face global bleaching crisis

Why is Germany maintaining economic ties with China?

|

|

We can, to some degree, relate, as many European scientists – and particularly those who research climate change and its impacts, as I do – have been forced to confront the politicisation of their disciplines, the distortion of their research and the promotion of “alternative facts” and vested-interest propaganda.

In fact, just two months ago at the annual General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union, for the first time in the body’s history, we debated issues around existential threats to science in general, the integrity of the scientific community, trust in science and what we can do to ensure that evidence-based science forms the basis for informed decisions and debate by policymakers and the public.

Later this month, we’ll watch as some of our American colleagues gather for the annual Broadcast Meteorology Conference of the American Meteorological Society, which will include in its programme a short course explicitly focused on the communication of climate science.

Never has accurate, fact-based communication of climate science been more urgently needed, and in modern history, it has rarely been so compromised. There is a clear trend, particularly evident in the US, of a growing distrust of “experts” who are branded as intellectual elites, rooted in a populist backlash towards the establishment.

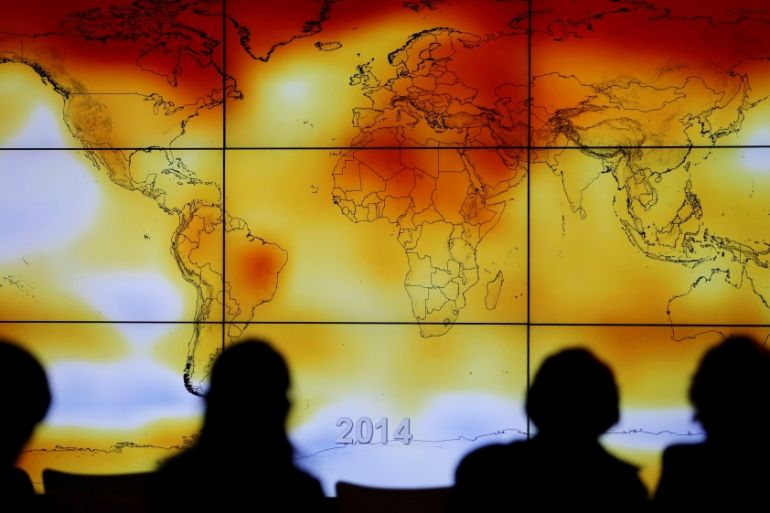

READ MORE: Climate change in pictures

This goes all the way up the rungs of government to the American president himself, who has called climate change a “hoax” and in his first 100 days in office has moved to curb spending on climate and earth science research and is overseeing an agency-wide scrubbing of climate science out of federal websites and publications.

As he announced the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement on June 1, Trump also left himself open to accusations of misrepresenting climate science to suit his own political objectives: after the US president quoted a figure from a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) study to support his argument that the Paris Agreement is ineffectual, MIT officials – including one of the study’s authors – declared that Trump had misunderstood their work and that they did not support a US withdrawal from the agreement.

|

|

The science of climate change, however, is clearer than ever. We see the fingerprints of human-induced global warming on more and more long-term climate trends. In the US and throughout the world, for instance, warmer temperatures are amplifying the intensity, duration and frequency of many weather events, none more evident than extreme heat. Western states have suffered through record numbers of heat waves since the turn of the century, with overnight temperatures often at historical highs. This is particularly dangerous as it doesn’t give the human body the necessary relief. Already, these heat waves are costing lives, and the scientific link between human-induced global warming and heat waves is crystal clear. The European heat wave of 2003 is estimated to have caused 35,000 premature deaths and was very likely a consequence of human interference with the climate system.

By listening to the best available science on climate change, we can better prepare for its impacts. By ignoring, censoring, or shunning our scientists, we put more Americans at risk. The alternative to informed decision-making is uninformed decision-making. Without evidence-based science, decisions of vital importance to humanity will be made founded in prejudice, emotion and ignorance. That is no way to run the planet. It is no way to plan our future.

Besides helping prepare for the impacts of climate change, science should guide our efforts to minimise them. For these mitigation efforts, the science is telling us that we don’t have much time. In fact, it’s saying that 2020 must be the target for peaking global carbon emissions. We must bend the curve of global greenhouse gas emissions towards a steady decline by the next US presidential election. If emissions continue to rise beyond 2020, the world stands very little chance of limiting global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius, the threshold set by the Paris Agreement, and a temperature limit that many of the world’s most vulnerable communities consider a threshold for survival.

The world has four short years to reverse our emissions trends to avoid the very real risk of dangerous and irreversible climate change, but we won’t get the policies we need without trusting and relying on the science that tells us that’s so. Science has no political affiliation, nor can it be bent to your will. You don’t renegotiate with physics and you aren’t about to “win” a deal with chemistry. We must not let rhetoric, vested interests or the blind dismissal of the overwhelming scientific consensus divert us from what we know is the right course of action ethically, scientifically and economically.

Jonathan Bamber is professor of polar science at the University of Bristol and president of the European Geosciences Union.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.