Trump’s strike on Syria: A convenient distraction

It’s not the first time a US president launches missile strikes that do not amount to much but boost ratings.

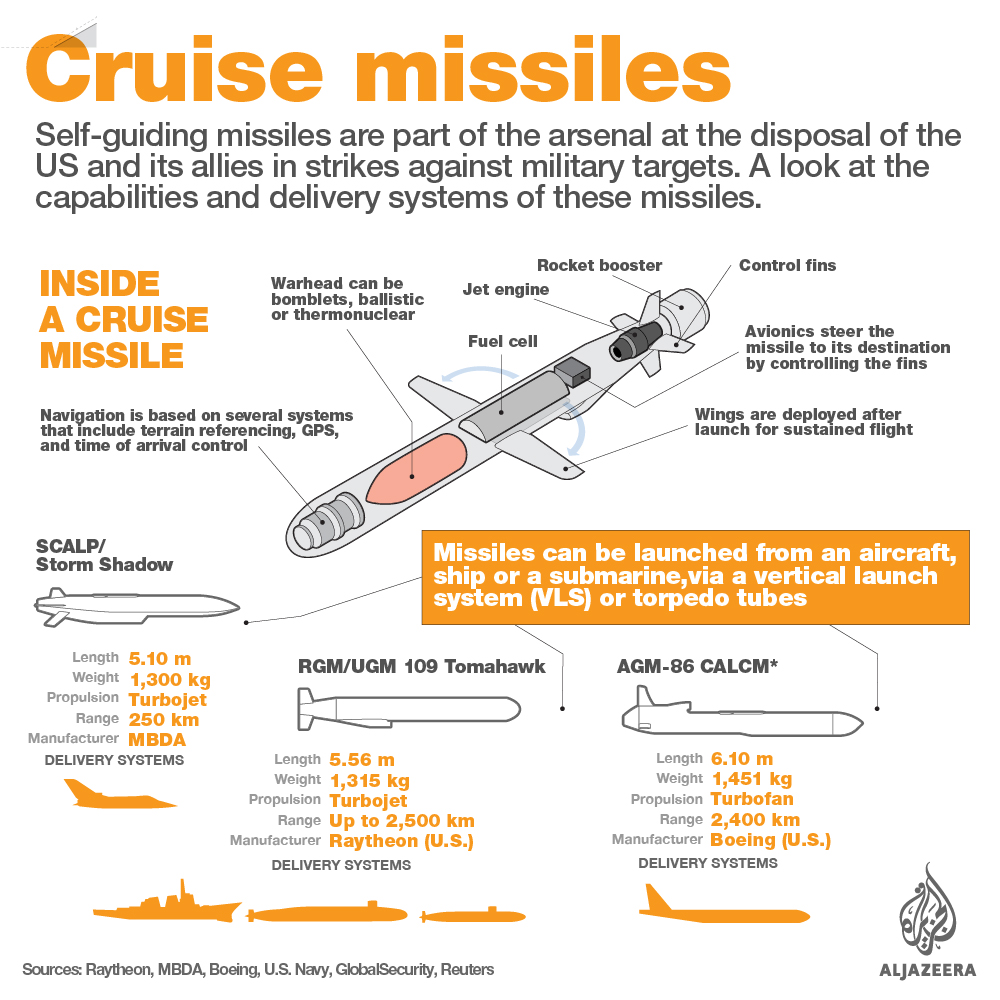

The United States launched 59 Tomahawk cruise missiles at a government-controlled Syrian air force base in the Homs province, purportedly where the nerve agent sarin was loaded on to aircraft that attacked a village in the rebel-held Idlib province.

Trump authorised this attack to ostensibly demonstrate that he will take a harder line against Syria, unlike his predecessor Barack Obama. While Trump’s actions represent the first time the US has attacked Assad’s forces since the civil war began six years, this military strike is embedded in a deeper history of America disciplining countries from the air over their weapons of mass destruction (WMD) facilities. Trump is in fact carrying on the legacy of President Bill Clinton.

The US launched cruise missile attacks against Iraqi WMD sites throughout the 1990s, and as of 2017 it is doing the same in Syria. The attacks seem to achieve little in the long run in changing the targeted government’s behaviour, but they provide symbolic proof to the international community of the US taking concrete action to discipline a country that violates the norm prohibiting WMD use.

The legacy of Bush and Clinton

|

|

On the 25th anniversary of the 1991 Gulf War I wrote: “Desert Storm represented the first time the US sought to shape, control, and configure the Middle East from the air.”

During the six-week air campaign of this war, aerial sorties were conducted against Iraq’s WMD sites. Yet UN weapons inspectors on the ground after the war still discovered both facilities and munitions that survived the air campaign.

With the Saddam Hussein regime having survived Desert Storm, the US tried to contain the Iraqi leader with no-fly zones in the north and south of Iraq, dubbed respectively Operation Northern and Southern Watch. Air strikes during these operations constituted a means of disciplining Saddam Hussein from the air, targeting Iraqi anti-aircraft radars and missile sites.

Additionally, in 1993 the Clinton administration authorised the launch of 23 cruise missiles against Iraq in retaliation for Saddam Hussein’s alleged plot to assassinate former president George H W Bush, which ended up killing one of Iraq’s most prominent artists, Layla al-Attar.

In 1996 the US launched 27 cruise missiles at defence targets in southern Iraq, after Iraqi troops entered Kurdish-controlled areas in northern Iraq and hunted down opponents of the regime.

This attack was followed up in 1998 with Operation Desert Fox, during which 415 cruise missiles were launched at suspected Iraqi WMD sites.

INTERACTIVE: From chlorine to sarin – Chemical weapons in war

These punitive aerial attacks did little to alter Saddam Hussein’s behaviour, and in fact subsequently intensified the conflict between the US and Iraq, where after 1998 the Iraqi president ordered increased efforts among his air defence forces to bring down an American aircraft, leading to an increase in US retaliatory bombings that continued right up to the 2003 Iraq war.

Trump’s military strike was ostensibly aimed at damaging Syria’s WMD programme. However, aerial military campaigns in the past have failed in this regard. While members of the Syrian opposition celebrated the attacks, in fact they are likely to do little damage to Bashar al-Assad’s survival, and only rally his domestic core of supporters, as well as Hezbollah, Iran, and Russia behind him.

The strike served a domestic agenda, showing that Trump can act against Russian interests, at a time when he is viewed as Vladimir Putin's puppet.

Fear of “boots on the ground”

In the media commentary that has emerged since the strike, I have noticed that pundits repeatedly have described the cruise missiles that struck Syria as “stand-off strikes”, fired from afar, in this case two American naval vessels in the Mediterranean. The terms used to describe such strikes are politically expedient for the Trump administration, opposed to its antithesis, sending in ground forces to take action.

While the decision to send boots on the ground in the form of US special forces to combat the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS) group in Iraq and Syria has backing from Congress and the American population, expanding the use of ground forces to strike targets linked to the Assad regime would have been seen as a dangerous escalation of the conflict. Even sending manned aircraft to take out the sites would have risked the downing of an American pilot.

However, a cruise missile strike carried little risk for the Trump administration, and distracted the public’s attention from his domestic political crises

A foreign policy distraction

In December 2016 there were predictions that Trump would attempt to “Wag the Dog”, or use a foreign crisis to distract domestic audiences and unite the nation behind him.

The strike served a domestic agenda, showing that Trump can act against Russian interests, at a time when he is viewed as Vladimir Putin’s puppet.

OPINION: We must not let chemical weapons become the ‘norm’

Trump did show emotion when moved by images of children killed in the chemical weapons attack. If he really wanted to do something for the children of Syria, Trump could open up the US to Syrian refugees rather than opting for a military strike that might make him look more decisive than Obama. This strike might improve Trump’s abysmally low approval ratings, but will do little to alleviate Syria’s humanitarian crisis.

Ibrahim al-Marashi is an assistant professor at the Department of History, California State University, San Marcos. He is the co-author of Iraq’s Armed Forces: An Analytical History.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.