Dayton ended the war, but did not make lasting peace

There must be some solution for this situation, and there must be a reason for optimism.

The oldest daily in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Oslobodjenje, recently published a mini-survey asking people about their first association with the Dayton Peace Accords, 20 years after it was signed.

“The first thing that comes to my mind is the vicious circle,“ replied Esma Palic, a war widow from Zepa, a village near Srebrenica. “I think about the vicious circle that we cannot break. Although, even if we can, we do not have any idea where we should go or how to continue.“

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Mama we’re dying’: Only able to hear her kids in Gaza in their final days

Europe pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

Birth, death, escape: Three women’s struggle through Sudan’s war

This feeling of bewilderment was overly expressed during the protests in 2014. People who were out on the streets all around the country were demanding a change of the system, even though they were not sure who should respond to their demands: the central government or local governments at entity and cantonal level? What about the international community’s say?

What everybody is sure about is that the system – which was based on the peace agreement – is not functioning.

Frankenstein state

The state structure created in Dayton brought into existence what Sarajevo-based law professor Zdravko Grebo calls the “Frankenstein‘s monster“ – an ugly and scary creature.

The peace that came with it is not much different. Children in Bosnia, even those born after the war, will mostly tell you that they feel like they are still living in the middle of the conflict.

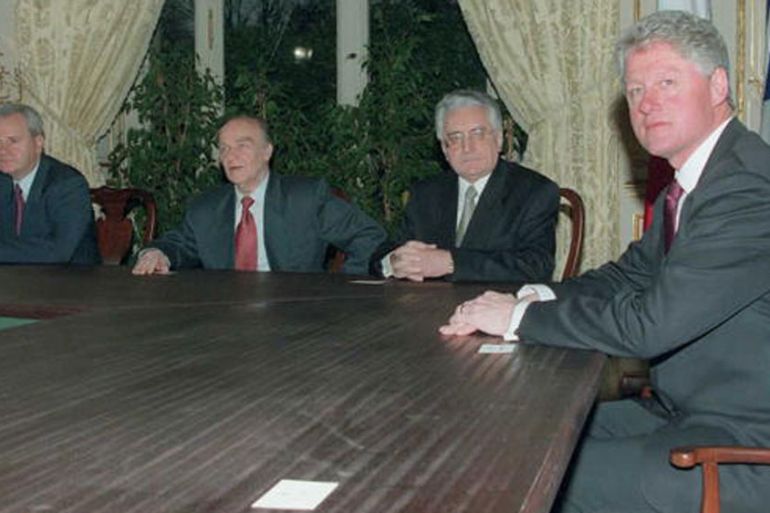

The peace agreement was negotiated in Dayton, Ohio, and signed in Paris in 1995. It basically defines every aspect of life in Bosnia, from the constitution to refugees’ return, regulations on public corporations and human rights.

This Frankenstein has three presidents, two entities and one independent district. It also has 10 cantons, more than 150 ministers at different levels, and a number of members of parliament that is hard to count.

It is hard to discern who is responsible for anything in this country. Moreover, nobody goes through a prism of accountability, neither local politicians nor the international community. But it is very easy to see who are the victims: citizens.

The system is served by an enormous bureaucratic apparatus. At the top of it all is the “international community“, represented through a number of organisations, some created by the Dayton Accords, others governmental, non-governmental and intra-governmental bodies – all with high influence.

The highest authority is given to the Office of the High Representative (OHR) and, for the past few years, to the EU Special Representative. The OHR has the power to impose decisions and to interfere in almost every aspect of public life in Bosnia.

Over the years, the international community has played a crucial role in the country, and although they never admitted it, their presence upholds the existence of a type of semi-protectorate.

Nevertheless, methods employed by the international community, their approach, goals and ideas, were changing with every new high representative (seven until today).

Changes were sometimes introduced with the arrival of new ambassadors from the most influential countries, meaning the US, the UK, Germany and some other European countries. For all of them the only road map was Dayton, but they just read it in different ways.

The bottom line is that it is hard to discern who is responsible for anything in this country. Moreover, nobody goes through a prism of accountability, neither local politicians nor the international community. But it is very easy to see who are the victims: citizens.

Ongoing unrest

Reports by international institutions or academics focusing on Bosnia have been warning for several years that the country is in a stalemate, run by irresponsible and corrupt politicians.

The international community now – as well as immediately after the war – is adamant that the only partners for them in Bosnia are the existing political elites which have not changed much in decades.

This unconditional support did not disappear – except rhetorically – even after citizens torched government buildings in 2014, expressing rage after 20 years of this miserable life.

Almost two years after the protests, one can still see the message on the facade of the cantonal government building in Sarajevo: “Those who sow hunger, harvest rage“, but it looks as if nobody really understands what this message is saying and how serious it is.

OPINION: Remembering Dayton, the accord that ended Bosnian war

Protests did not achieve a government reshuffle or a systemic change at large, but did initiate a public discussion. Today, more and more citizens are talking about social justice, the faults of the system and, more importantly, finding shared similarities instead of differences.

Twenty years after the end of the war youth unemployment in Bosnia is almost 60 percent, while more workers are protesting on the streets for their eroding basic rights.

That is how living with this peace agreement looks.

Additionally, thousands of people have left the country over the past few years. Some left with their families, leaving villages and towns almost empty – a scenario reminiscent of the war.

Action needed – more than ever

What Bosnia needs today are new voices, new people, new ideas, and new politics: somebody who can act responsibly and be accountable.

Current political elites cannot meet the demands of Bosnians, nor address the endemic problems in the country.

At the same time, the international community – which is not a monolithic body and has numerous voices with different agendas – should start accepting its limits.

Furthermore, the international community also needs to realise that democracy is something that is difficult to impose, especially in post-conflict countries.

Dayton Accords: 20 years of precarious peace in Bosnia

Finally, the change can be achieved only if it can address local needs and demands – but needs of citizens, not political elites.

In Bosnia, the international community efforts were led mostly by ideas imposed from the outside, and implemented with local politicians.

Today, there is the chance that ongoing protests will spread around the country, reaching more people. If these voices are not heard, it can pose the danger of a new wave of unrest.

For the current political elite it can represent a threat to their comfortable rule. And they will not take that threat lightly.

One of their methods to weaken this dynamic protest movement would be to arouse old nationalistic threats and divisions. That would be the only thing that can keep them in power.

Like Milosevic 25 years ago, Bosnian politicians today are in control of the media, judiciary, army, police, even culture and sport. And all that can be turned into arms for awakening nationalism when needed.

There must be some solution for this situation, and there must be a reason for optimism. But, it is almost impossible to see it through the Dayton Accords lenses we have worn for the past two decades.

Nidzara Ahmetasevic is an independent scholar and journalist from Bosnia and Herzegovina, currently a fellow with the Alliance for Historical Dialogue and Accountability at Columbia University.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.