Charles Correa and India’s smart city

Remembering India’s visionary architect and his legacy – a blueprint of inclusivity for Modi’s planned smart cities.

The career of the visionary Indian architect Charles Correa, who passed away last week at the age of 84, serves as a window on modern India as much as that of any great Indian public figure of the 20th century, whether Gandhi or Tagore, Ambedkar or Satyajit Ray.

Partly, this was because of Correa’s highly refined awareness of the place and power of architecture: spanning the public and private lives and material and metaphysical impulses of human beings, borrowing from a range of inspirations both traditional and modern, drawing from disciplines all the way from the fine arts to urban planning.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

But it was also because Correa’s willingness for six decades to go beyond the usual world of the elite architect, centred around a single building or project.

|

|

Correa was willing to get his hands dirty with the practical problems of mass housing and transportation, as the implications of the tidal wave of migration to the cities that would – as early as the 1960s – soon wash over India and present to its urban planners challenges on a scale the developed world had never faced.

A social vision

Repeatedly in his work, Correa insisted that the architect in modern India, as much as the representatives of its maturing democracy or those in charge of its economy, could radically improve the lives of millions of people by bringing a combination of invention, intelligence, and poetry to man’s use of space.

“At its most vital, architecture is an agent of change. To invent tomorrow; that is its finest function,” he wrote in 1984. Correa’s was, then, a double quest: On the one hand, for a modernist architecture, it was underpinned by Indian ideas and forms and adapted to the peculiarities of the Indian climate; and on the other, a quest for a vivid new imagination of how Indian cities could answer at a low cost, and without discounting the human need for beauty, the spatial needs and predispositions of their toiling and burgeoning masses.

|

Even when architecture was animated by political vision, politics itself could stymie its goals.

|

“The rural migrants pour into our cities. They are looking not merely for houses, but for jobs, education, opportunity. Is the architect, with his highly specialised skills, of any relevance to them?” he wrote in his portfolio book Charles Correa in 1985. “This will remain the central issue of our profession for the next decades. To find how, where and when he can be useful is the only way the architect can stretch the boundaries of his vision beyond the succession of middle and upper-income commissions that encapsulate the profession in Asia.”

Yet the catch was that, to be successful, the socially ambitious architect’s vision was dependent on the goodwill, intelligence and commitment of other individuals and institutions with their own interests, from municipal corporation to local politician or slumlord. Even when architecture was animated by political vision, politics itself could stymie its goals.

For instance, Correa designed some of the most distinctive and beautiful buildings of modern Mumbai – from the iconic, terraced high-rise south Mumbai apartment building Kanchanjunga to an entire low-rise, sylvan township in the northern suburb of Borivali where I myself lived with great pleasure for several years. His stamp is all over one of the world’s great metropolises.

![Kanchanjunga Apartments in Mumbai. [Peter Serenyi/Massachusetts Institute of Technology]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/f0bd6075da754b2492218aabb3772e1d_18.jpeg)

Bringing change to modern India

In the 1970s, Correa was appointed the chief planner of the twin city of New Bombay, a city built from scratch across the harbour to ease the load on the island city. But for want of political will, the new township never took off in the way that it could have.

Meanwhile, the island city itself became, as a result of the machinations of its ravenous politician-builder nexus, ever more dystopian in the course of his lifetime, with even the buildings of the rich almost as impoverished, architecturally speaking, as the sea of shantytowns and disastrous “slum-rehabilitation” projects to which the poor were condemned. Famously, Correa called Bombay “a great city but a terrible place”. The many frustrations of Correa’s career, as much as the successes, make his life story a parable of the difficulty of bringing about change in modern India.

Even so, the wide range of public and private projects executed by Correa across India and the ambition of not just his architectural, but also his social vision, seems especially relevant today as a template for new visions of urban India – and indeed as a check on them.

For this is the year that the new Indian government of Narendra Modi hopes to roll out its vision for a large-scale push to create as many as a hundred new Indian “smart cities” by 2020 as a way of meeting the needs of a rapidly urbanising society that can no longer be accommodated in the metropolises of old.

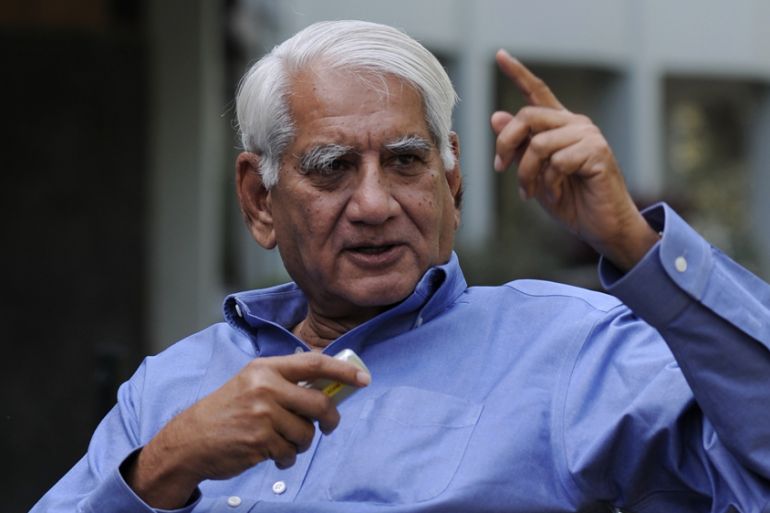

![Charles Correa, India's visionary architect, passed away on June 16 [Getty Images]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/a1424c9d99d14c74bf4258a6b6bb78e0_18.jpeg)

Correa’s legacy

The virtues of these new cities is that, since many of them will be built from scratch (some existing cities will be upgraded to become “smart”) they won’t be hostage to the entrenched bottlenecks of power and subversion and the histories of urban decay that have derailed many other attempts to improve the living conditions of people in older Indian cities such as Mumbai. They could be the sites of ambitious new experiments in housing and public transport, and generate hundreds of thousands of jobs for an economy bulging with the pressures of a rapidly growing workforce.

But the worry is that the proposed smart city, with all its efficiency and planning, will not be a good or hospitable city in the democratic sense. Some suspect it would essentially be a glorified, fully air-conditioned special economic zone catering to the needs – and income levels – of the middle class and above, and sweeping unwanted migrants back into the rural heartlands from which they arrive. (So far, there has been little input from the government about how its smart cities project ties up with its other declared ambition, housing for all.)

Against this technocratic, big-capital-controlled, resource- and energy-intensive vision of the city, stands the accumulated work and literature by Correa on how to make Indian cities low cost, energy efficient, aesthetically pleasing and egalitarian, with provisions even for hawkers and pavement-dwellers, existing at the level of the “bazaar economy” and further enabling it.

To be truly successful, the proposed Indian smart city will have to be more humble, more inclusive, more imaginative in its response to not just man’s material needs but his metaphysical ones. Briefly, it will have to be more Correan.

Chandrahas Choudhury is a novelist and columnist based in New Delhi. His work on Indian politics appears regularly on Bloomberg View and in The Caravan.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.