Egypt, de-democratised

Scholar Irfan Ahmad argues that the Egyptian military staged a coup d’etat that has set democracy back in the nation.

It is a coup d’état!

Let’s call a spade a spade: despite military’s denial that it didn’t plan to stage a coup d’état, what it did on July 3 was precisely a coup. The arresting visual of the announcement of the coup on the state television had elements of exactly that postmodern spectacle.

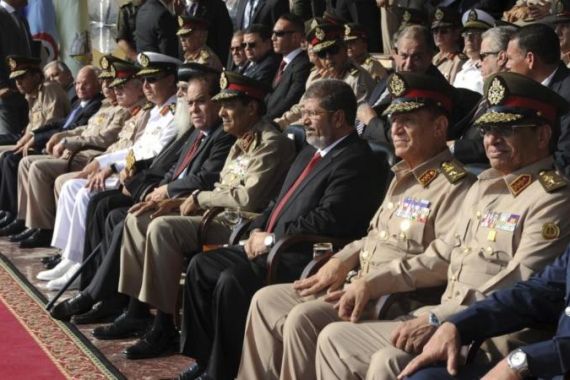

Unlike the 1999 coup by Pakistan’s General Pervez Musharraf, General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s was almost surreal. As he announced in his shrill voice the unconstitutional deposition of the elected President Mohammad Morsi, on his right were seated heads of other wings of armed forces, including the liberal poster-man, Mohamed ElBaradei.

On General al-Sisi’s left were, inter alia, Grand Sheikh of Al-Azhar, Pope Tawadros of the Coptic Church, a member of the al-Nour party as well as a representative of the youth. There were no women. One by one all these figures spoke to back the coup and thereby subverted Egypt’s fragile democracy.

To General al-Sisi, this coordinated and well-thought-out coup was a ‘patriotic‘, not a ‘political’ act. Think of George Orwell and the masterful twist of language!

The subversion of Egypt’s democracy was implicitly hailed by democracy’s custodians, the Western states, for none of them – not the USA, the EU, France or the UK – named the overthrow of the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP)-led government as a ‘coup d’état’, leave alone condemned it.

By failing to do so, these Western democracies found themselves as unlikely bedfellows with Saudi Arabia and the UAE, two states that also welcomed the coup. Does not the statement of British Foreign Secretary, William Hague that ‘only democratic processes and government by consent will bring the stability and prosperity that the people of Egypt seek’ mislead people to think that the Morsi’s government was not based on consent?

|

To recreate democracy Egypt ought to courageously resist any act of de-democratisation, from within as well as without |

If the mere number of people taking to the streets is a sufficient condition for a government to be overthrown, then, did the governments of Tony Blair and George W. Bush met this condition as millions had marched against their unethical war in 2003?

My point is not to justify whatever Morsi did or to discredit the anti-Morsi protests. Clearly, such protests are integral to a thriving democracy. The question, however, is: how such protests in the name of democracy end up befriending its current adversary, the unelected military?

How is it that the ‘liberal-secular’ opposition, that so detests the Islamism of the FJP, includes the al-Nour party of Salifis who are no less religious than their Brotherhood counterparts? Does not ElBaradei’s liberalism wedded to unbridled military might prove Uday Mehta‘s contention that liberalism has historically served empire?

You are a democrat, but are you a friend?

The July 3 coup d’état is a classic example of de-democratisation engineered by the powerful states, invariably the Western ones. In an earlier piece on Al-Jazeera, I argued how the West has historically used Latin America and the Middle East as laboratories of de-democratisation.

In the case of Egypt, it is not yet clear to what extent the internal and external actors converged to enact her de-democratisation. However, this much is clear that if a less powerful democratic state does not serve the interests and identity of the powerful – within and without – democracy is easily sacrificed to ensure the hegemony of the powerful. What ultimately matters is not being a democrat but being a friend. In some ways, Egypt of 2013 resembles Haiti of 2004 and Ireland of 2008.

In 2004 France and the US organised a coup against the elected President of Haiti, Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Aristide was put on a 20-hour flight to the Central African Republic. Even the Haitian officials didn’t know about his destination. As I write, we don’t know where Morsi is. Aristide maintains that he was abducted.

Let’s recall that in 2000 elections Aristide was elected as president second time. Two key factors for his ousting were his refusal to submit to Washington and, his demand that France, the former colonial power, pay a sum of US$21bn it had extorted from Haiti.

In 1805, Haiti was the first country in Latin America to become free as a result of slave revolt. All powerful countries at that time, including the US, sided with France and declined to recognise Haiti’s freedom. In desperation for recognition and under threat of being recolonised by France, the Republic of Haiti agreed to pay 150 million Francs to France for her economic loss.

Haiti continued to pay ‘debt’ to France for decades. Aristide demanded that the money France extorted from Haiti should be returned to build hospitals, schools and roads. The French Premier sent Regis Debray to Haiti to delegitimise Aristide’s claim.

During his visit Debray found that ‘no members of the democratic opposition to Aristide took the reimbursement claim seriously’. Clearly, he sought to mislead people that Aristide’s government was undemocratic. Western states and Egypt’s politicians opposed to Morsi depicted the latter in a similar fashion. Furthermore, rather than help Aristide in his welfare campaign, the US-funded opposition, armed groups and the so-called civil society institutions undermined Aristide’s government.

Unable to deal with him politically, Senator Jesse Helms, a Republican from North Carolina, called Aristide a ‘psychopath’. The day Morsi was ousted BBC interviewed a woman named Suraiyya, who dubbed formations like FJP and Morsi as “Islamofascist”. The BBC journalist didn’t bother to ask her how she applied such a label. The synergy between the interviewee and interviewer was just perfect and subverted any legitimacy Morsi may have possessed.

In June 2008 Ireland held a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty on European Union reform. Over 53 percent rejected the Lisbon Treaty. This rejection, however, went against the wishes of Europe’s elites.

Instead of accepting what the Irish people sovereignly decided, The Guardian delegitimized the Ireland’s popular will as follows: ‘Less than 1 percent of the EU’s 490m citizens appear to have scuppered the deal mapped out in Lisbon that was meant to shape Europe in the 21st century’. A similar logic was/is at work in the case of Egypt. Valery Giscard, a key author of the Lisbon Treaty, told a radio journalist:

Giscard: ‘The Irish must be allowed to express themselves again’.

Radio Journalist: ‘Don’t you find it deeply shocking to make people who have already expressed themselves take the vote over?’

Giscard: ‘We spend our time re-voting. If we didn’t, the President of the Republic would be elected for all eternity’.

|

|

| What is SCAF? |

It is clear what exactly Giscard meant by his comment: namely, the Irish people must keep on voting until they give the desired result he and his like-minded politicians wanted to hear and promote. The problem with Morsi and FJP was precisely this; they didn’t say exactly what the powerful wanted to hear, and their ideological adversaries were happy for popular revolt to subvert democratic processes until their ideal outcome may arise.

Future of democracy and Egypt

Now that Egypt stands de-democratised and the Army has issued a road map, what is to be done? Let’s hope that General al-Sisi’s model is neither Pakistan’s General Musharraf nor General Zia-ul-Haq. Furthermore, to responsibly answer this question is to transcend narrow, exclusive interests of any group and build a plural, dialogic political community acknowledging, not negating, differences.

This entails redefining democracy democratically so that it flowers into value in its own right, not simply as a bare tool that serves one’s partisan interests. It must alter, even abolish, rather than reproduce the dominant dualism between ‘friends’ and ‘foes’.

If the goal is to nurture as well as redefine democracy in its nascent stage, none of the political formations, including the FJP, should resort to violence. That will deprive Egyptians of an immense possibility of imagining politics anew.

To build a truly democratic Egypt is to follow the path and ideals of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, a great 20th century icon of non-violence and democracy. In short, to recreate democracy Egypt ought to courageously resist any act of de-democratisation, from within as well as without.

Irfan Ahmad is a political anthropologist and a lecturer at Monash University, Australia and author ofIslamism and Democracy in India: The Transformation of Jamaat-e-Islami (Princeton University Press, 2009) which was short-listed for the 2011 International Convention of Asian Scholars Book Prize for the best study in the field of Social Sciences. Currently, he is finishing a book manuscript on theory and practice of critique in modernity and Islamic tradition.