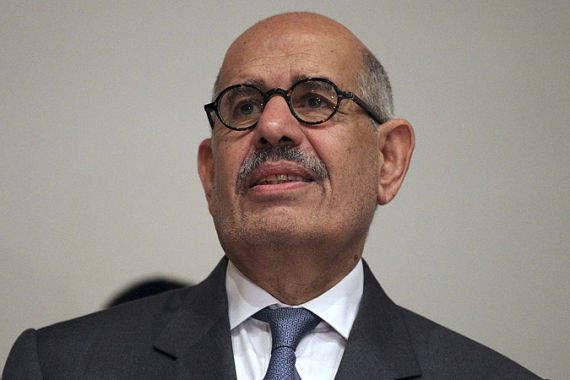

Anti-democracy: A response to ElBaradei

The Egyptian opposition leader’s criticisms of President Morsi are misguided and hypocritical.

Dr Mohamed ElBaradei’s June 23 op-ed in Foreign Policy suggests that Egypt’s President Mohamed Morsi – one year into a four-year term – should either resign, or be forced, from power. ElBaradei’s article comes in the context of the “rebel” campaign, which is designed to force Morsi to call for presidential elections nearly three years before they are due.

In his op-ed, ElBaradei – an opposition leader and former director of the International Atomic Energy Agency – complains about the lack of law and order in Egypt. He conveniently ignores the fact that Egypt has suffered from a general lawlessness that began once the uprising against Hosni Mubarak ended, and well before Morsi’s term began. Also, the current government does not have complete control over corrupt, Mubarak-era security forces – many of whom have been protesting against Morsi and striking in recent months – and analysts have noted that purging Egypt of Mubarak’s “deep state” will take years.

He also disregards the fact that elements in Egypt’s opposition are responsible for much of the organised violence witnessed recently in Egypt. The presidential palace was repeatedly firebombed last December, and other government buildings, 30 Muslim Brotherhood offices, and four Muslim Brotherhood buses, among other things, have been set ablaze.

ElBaradei laments the state of the Egyptian economy, placing the blame squarely on Morsi’s shoulders. The situation is not quite so clear, however, in part because the Morsi administration has had to endure constant instability, which has discouraged investment and tourism. The first calls for a “revolution” against Morsi began last August, just weeks after he was elected, and some in the opposition have proclaimed their intention to make life so difficult for Morsi that he is forced to resign.

|

|

| Mass protests mark Morsi’s tumultuous year |

Some members of Egypt’s opposition, including members of ElBaradei’s National Salvation Front, began calling for a presidential election “do-over” last summer, as soon as election results came in. Importantly, members of Mubarak’s ousted National Democratic Party have openly taken part in the rebellion against Morsi, and leaders in ElBaradei’s National Salvation Front have recently announced their alliance with at least some Mubarak regime remnants.

Like Egypt’s security situation, ElBaradei ignores the fact that the country’s economy was in shambles before Morsi took power, and that several of his National Salvation Front comrades served as ministers in the post-revolution military-led government that ruled Egypt for about 16 months, during which time foreign reserves dipped from $36bn to $14bn. Morsi’s government has managed, in spite of constant chaos in the streets, to modestly increase reserves to $16bn.

ElBaradei complains that Egypt is being “Brotherhoodised” and that Morsi has failed to build a coalition government. The reality is actually more complicated. Only 35 percent of cabinet ministers and governors hail from the Muslim Brotherhood, and that figure would be significantly lower if ElBaradei’s opposition hadn’t systematically rejected participation in government. Many high-level posts, including ministerial and vice president positions, have been offered to opposition figures, and nearly all have declined. Some of the rejections came early on in Morsi’s tenure. For example, Hamdeen Sabahi, ElBaradei’s National Salvation Front partner, acknowledged last summer that Morsi offered him the position of vice president. Sabahi declined.

ElBaradei is absolutely right that the Morsi government has made key mistakes, and I have criticised them both for policies they have implemented and have not implemented. But calling for an election “do-over” every time the opposition decides that the government is “not qualified” is not in Egypt’s best interest.

I have defended ElBaradei until a little over a year ago, when I began to notice a consistent stream of anti-democratic discourse and tendencies from him. In early 2012, when Egypt’s first democratically elected parliament was disbanded on a technicality by corrupt members of the judiciary, ElBaradei supported the decision.

During the presidential election season in early 2012, ElBaradei announced that the elections were a sham because of the spectre of the military and the absence of a constitution. It is too bad he didn’t run. He may have won, and then it would have been him issuing a presidential decree to remove the military from the political scene and watch over Egypt as it prepared its post-revolution constitution.

|

ElBaradei is right that Egypt is currently plagued by the ‘same mode of thinking as in Mubarak’s era’. But the dictatorial mentality and tactics exist primarily on his side of the political fence. |

In November 2012, Morsi, in what he claimed was an effort to save Egypt’s last democratically elected institutions, issued a controversial decree giving himself sweeping but temporary powers. ElBaradei announced, in rhetoric that would have made Joseph McCarthy blush, that Morsi had become a “pharaoh”, a dictator worse than Mubarak. Interestingly, ElBaradei insisted all the while that Morsi supported a constitution that sets out term limits and which, according to Western experts of constitutional law, greatly limits presidential powers.

On December 6, in the midst of the crisis that followed Morsi’s decree, ElBaradei appeared to put his democrat hat back on and called on Morsi to hold a “national dialogue” to end the crisis. The next day Morsi called for a dialogue, declaring that he was willing to compromise and that he hoped all opposition figures would attend. ElBaradei rejected the call.

The national dialogue went on without ElBaradei – who has argued that dialogues are pointless because Morsi doesn’t listen to any opinion other than his own – on December 9. Morsi began the meeting by telling the 54 attendees that he would leave the room, allow Vice President Ahmed Mekki to chair the meeting, and agree to whatever the group decided. The dialogue led to Morsi cancelling the controversial elements of his decree. Had ElBaradei showed up, he may have been able to convince the group to also delay the constitutional referendum. Another national dialogue was held on December 21, this time to explicitly discuss the draft constitution. Again, ElBaradei didn’t show up.

ElBaradei also discussed the contents of Egypt’s constitution in his op-ed, which he has called the “Muslim Brotherhood Constitution” – even though only 32 Brotherhood figures were on the 100-member constituent assembly and 22 Egyptian parties representing the country’s political spectrum agreed to the composition of the assembly in June 2012. In December, ElBaradei delivered a video presentation about the constitution, in which he claimed that the document forces children to work, among other inaccurate claims. ElBaradei’s group has been invited to propose revising problematic articles, and Morsi has promised to form a committee that will work to remove or revise problematic articles once a permanent parliament is elected. ElBaradei has rejected these efforts as well.

ElBaradei is right that Egypt is currently plagued by the “same mode of thinking as in Mubarak’s era”. But the dictatorial mentality and tactics exist primarily on his side of the political fence.

Mohamad Hamas Elmasry is an assistant professor in the Department of Journalism and Mass Communication at the American University in Cairo. He has published research on the sociology of news and Arab media in international peer-reviewed journals.