Iraq: Imagine a different future

Iraqis are becoming increasingly adept at defending and advancing their rights across the political and social spectrum.

This is the first in a two-part essay that discusses how 10 years after an invasion and occupation that killed hundreds of thousands of people, destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure and unleashed an ongoing storm of brutal sectarian violence, Baghdad is in the midst of a year-long celebration of its return as a “capital of Arab culture”. Part 2 will explore how artists, educators and (h)ac(k)tivists are moving Iraq slowly to the kind of socio-political space in which fundamental change can occur.

Imagine if New York, Paris or London had been closed off from world since 1968, subject to over three decades of dictatorial rule, three wars, two foreign invasions, a dozen years of crippling sanctions that claimed over 100,000 of its children, and almost a decade of occupation and deadly inter-communal conflict.

This is what Baghdad has gone through for most of the last half century.

And yet, 10 years after an invasion and occupation that killed hundreds of thousands of people, destroyed much of the country’s infrastructure and unleashed an ongoing storm of brutal sectarian violence, Baghdad is in the midst of a year-long celebration of its return as a “capital of Arab culture“; indeed, as a fledging voice in the global cultural ecumene.

Iraq remains a deeply troubled country. Almost two years after the official US withdrawal, the Maliki government continues to demonstrate a decided lack of interest in offering the country’s once dominant Sunni majority a significant enough share of power to drain the most important cause of the ongoing sectarian conflict. Nor has it displayed the kind of managerial competence that would enable it productively to utilise the roughly $100bn the country earns from oil exports (that number will likely more than double in the next few years) to reconstruct – never mind further develop – the country at a pace commensurate with the resources at its disposal.

Instead, the government has adopted an increasingly harsh hand against all opponents, who are more often labelled as terrorists than engaged as participants in a national political dialogue on the country’s present and future course. The massacre in Hawija in late April and the ongoing harassment (and worse) of activists across the political spectrum – especially Sunnis – are the latest examples of such policies.

LA Times correspondent Ned Parker well describes the tensions sweeping across Iraq today, including in Baghdad, in a May 10 article from the capital. He argues that the country is at a dangerous crossroads, at which civil war and break-up increasingly seem the two most likely paths before it.

But these troubling realities are not the whole story; far from it.

The Museum versus the Archive

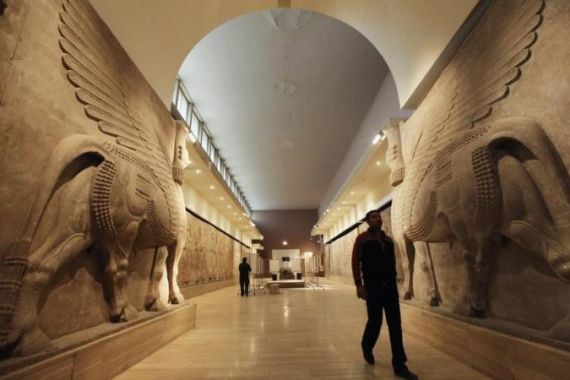

The stark contrasts characterising life in Iraq today, and the promises and dangers they portend, are well captured by the conditions at two of Iraq’s most important institutions -the National Archives and the National Museum. Both were nearly destroyed in the early days of the US invasion in 2003; the former by US bombs, the latter by looting. A decade later, their conditions are quite different. The Museum has recovered perhaps the majority of the pieces that were stolen. During a visit last week (tellingly, the Museum remains closed to most Iraqis, but it was opened specially for participants in an international conference I was attending) I saw the collection that was literally breathtaking.

|

| Spotlight

Ten Years in Iraq

|

Thousands of artifacts, from tiny cuneiform cylinders to 6 by 10 metre wall carvings, and every kind of vase, bowl, figurine and human-headed bull statue in between – are on display, providing a visual tapestry for understanding Iraq’s ancient and early Islamic history. However much has been lost, and is no doubt irreplaceable, the overall image(s) of Iraq’s famed ancient history, which in so many ways is at the core of human cultural history, is according to the museum officials with whom I spoke relatively intact.

A very different situation portends at the National Archives, which along with much of the National Library were destroyed by US bombs during the 2003 invasion in an act that historian Juan Cole describes as “Cliocide” – the destruction of a country’s historical legacy so intense it can be considered an act of cultural genocide (Clio is the ancient Greek muse of history). The loss is unfathomable.

I did not have the chance to investigate the status of the ancient, early Islamic and medieval documents when I visited the Archive. However, when I asked officials about the Ottoman era documents I was told they were almost entirely destroyed. The same occurred with the Republican-era documentation of the 1950s and 60s, from the end of the monarchy till the Baath Party seized power in 1968.

Let us return to occupied New York – or better, Washington, DC. Imagine that the vast majority of the documentary record of American history contained in the Library of Congress and National Archives between the 17th and 20th centuries was destroyed by Iraq during its invasion of the US. Imagine that almost none of the destroyed documents -the collective heritage, history and thus identity of the American people – had even been explored yet by scholars, so there have been few if any histories published that used these documents, and thus could at least partially preserve their contents for future generations. Imagine, then, that centuries of American history were simply deleted or erased, gone forever, never to be known by anyone – as if they never happened.

Imagine too that the presidencies of Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson were in good measure also lost to the historical record. The chance to study them gone with the wind like the millions of flecks of ash that floated away from the rubble of the Iraqi National Library after the US bombed it. Now imagine trying to understand the subsequent history of the US when so much of the past is forever gone from view. That is precisely what has happened in Iraq.

Having spent much time in the central Ottoman archives in Istanbul researching the 19th and early 20th century history of Iraq, I can say that few if any of the destroyed documents exist there in any form, or in the British, French. Austrian or German archives as well. They are simply gone. We do not even know what we will never know.

Despite the horrific nature of the loss, what is available to scholars – and the staff of the archives is working to ensure that what remains is digitised and permanently preserved for future generations – is a treasure trove of documents about the British Mandate era and, a generation after it ended, Baathist rule as well. Thousands of boxes of documents are waiting to be studied by scholars; there is little doubt that academic careers will be made in the document room as a new generation of Iraqi scholars and their foreign counterparts begin to explore them. Just one file I randomly opened contained a host of documents from the first days of Baathist control in 1968; another discussed the changing nature of land tenure in British-ruled Mesopotamia.

Steps forward and back

The state of the Museum and the Archives, the destruction and the hope they contain, exemplifies the contradictory dynamics of life in Iraq as it slowly, and hopefully surely, emerges out of a decade of war, occupation and violence, and two generations of dictatorial rule, war and sanctions before that. So much has been lost, and yet with what remains much can be done and a future, however tentatively, built.

On the one hand, if one remains pessimistic it would certainly be easy to travel across the largely Sunni Arab mid-section of Iraq and northern cities such as Mosul and sense impending doom, a feeling grounded in the ongoing reality of living among or near the communities that lost the most with the US invasion and occupation, and the emergence of a Shia-dominated Iraq in their wake.

But however deep and structural remain Iraq’s divisions and the problems that attend them, there are important countervailing signs, and some realities, auguring for at least the possibility of a more positive future. For Kurds and Shia, who together make up well over 80 percent of the country’s population, the ending of Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime created the chance for a political and communal life that would have remained impossible under the former system. Their success does not equal Iraq’s; indeed, it has encouraged conflict with Sunnis on the butt end of the new system. (There is even talk today by Sunnis of following the Kurds’ example and establishing an autonomous region, if not leaving the country all together in order to best protect their interests.)

Despite the government’s authoritarian streak and continued inter-communal and regional tensions, the present conflicts exhibit the potential for a transformation towards the kind of political struggles by citizens that could help heal rather than further tear apart the country. This is exemplified by attempts by local leaders in Fallujah, once the capital of the violent Sunni insurgency, to build a peaceful grassroots resistance movement against the government explicitly modelled on the present pro-democracy wave sweeping the region. The violence of the government crackdown can in fact be seen as confirming its potential to challenge Iraq’s present balance of political power.

Indeed, as many Iraqis like to tell it, the problem is not between individual members of the country’s communities; it is at the political level, where incentives to ameliorate many conflicts that pit Iraqis against each other often lose out to the narrower but more immediate benefits that can accrue to those who would not but little incentive to work towards are various interests who benefit from ongoing conflict as long as it can lead to a bigger slice of Iraq’s considerable and growing economic pie.

|

|

| People & Power – America’s War Games |

However problematically, the Iraqi Parliament is functioning (particularly at the committee level, where the structures of the country’s political future are slowly being created). As important, it is both open to pressure by various groups within society, and even shows some backbone against Maliki, with the Parliament Chief demanding the present cabinet resign after a report by the body blamed security forces for the bloodshed. The electoral process is relatively fair; indeed, Prime Minister Maliki’s political woes are likely to cost him significantly in the upcoming elections. Even Moqtada’ al-Sadr has become a powerful “good governance” advocate, taking on government abuses and corruption with the same political deftness and inter-communal spirit that characterised his resistance against the US during the occupation.

More broadly, despite numerous areas in which systematic abuses of political, civil and human rights remain common, Iraqis are becoming increasingly adept at defending and even advancing their rights, across the political and social spectrum. Almost all the news one reads, watches or hears about Iraq is negative, with a few culture-themed articles to keep the reporting interesting. And despite all the negativity that continues to exist, when you are in Iraq and meeting with Iraqis from the creative and rights communities, an entirely different sense of Iraq’s present realities and future possibilities emerges. Iraq suddenly looks not like a laggard in a region moving, however haphazardly, towards a more democratic future. Instead, the country’s complexities come into full view: Its political dynamics closer to the cutting edge of regional change and its cultural production equally on the regional avant-garde.

‘No one thinks about the car bombs anymore’

So explained one young Iraqi civil society activist when I queried about the wisdom of leisurely driving around the city, never mind with unmistakably foreign-looking passengers in the car. His answer may not reflect the sentiments of all Iraqis; but it is clear that despite the uptick in violence during April, Baghdad is, after so much bloodshed, once again becoming a livable city. For me, the most immediate indicator of progress is the fact that one can breathe the air without feeling sick, a major improvement over the height of the occupation, when electricity was so unreliable that the city hummed with the cacophonous polyphony of thousands of old and extremely polluting diesel generators.

To be sure, the city writ large remains highly militarised, as soldiers, security personnel and check points set up at as little as every 50 metres. Getting into and out of the International (formerly Green) Zone is almost as complicated and difficult as getting into – or worse, out of – Gaza. Getting into the airport when you have to leave is almost as bad, while the Museum remains as heavily guarded as most Treasuries. Roads are still dotted with checkpoints packed so close together that they paralyse traffic, making travelling on a hot weekday afternoon even more oppressive than Cairo.

Despite all the obstacles, the fact is that Iraqis now routinely move across the city in relative safety, whether running to a meeting or heading out for a midnight falafel, is no longer novel; it is today the norm. While Baghdad can still have the feel of a post-apocalyptic city, the blast walls that cordon off so many neighbourhoods and most every significant building are slowly beginning to come down. One can even imagine a cityscape dotted with the kind of kitschy post-modernist skyscrapers that define the skylines of Abu Dhabi, Doha and Dubai if Baghdad can pass the next few years without a major explosion of violence. Whether this is desirable is another matter entirely. As a senior politician from one of the country’s main religious parties put it as we drove around the city discussing possible futures, “Let that happen to another city. Let Baghdad keep its old character.”

Even the hostility (and high potential for violence) towards foreigners – which defined Baghdad in the mid-to-late 2000s – has substantially faded. Seeing a clearly identifiable Westerner on the street or in a café still turns heads, but it is most likely to generate smiles and even request for a photo, perhaps to prove to friends that European or Americans are actually coming to Iraq again.

A young Iraqi friend, who lost his father and older brother in a suicide car bombing at the height of the violence, best summarised the realities of the present and the possibilities for the future. He explained that he hoped his mother could leave Iraq and live with one of his surviving siblings in North America. And yet he remains determined to stay in Iraq in order to help build a different future.

Emerging rights cultures

Few who have not lived through the level of tragedy with which so many Iraqis live can fathom how someone who has lost so much has the ability to build their lives so constructively. One of the more positive but least reported aspects of Iraq’s political development is the evolution of a human rights culture throughout the country at the grassroots level. As Hanaa Edwar and Jamal Jawahiri of the Iraqi al-Amal Association(one of the premier human rights groups in the country) told me, there are today hundreds of independent NGOs that work in increasingly close coordination and have achieved important victories in a number of areas, including gender, health, education and children’s rights. Discarded as a “Western” threat to local/Islamic values only a few years ago, human rights discourse has now become a given across the political spectrum, thanks to the constant efforts by their and similar organisations.

“The rest of the Arab world can learn a lot from our experiences. We are advising colleagues in Tunis, Libya and Egypt on issues related to proper constitutional language, parliamentary procedures and protecting women’s rights or free speech,” they went on.

In addition to the movements traditionally associated with political parties and various syndicates, there are hundreds of independent civil society organisations across Iraq building not just grassroots political cultures, but cultures of civic engagement more broadly as well. It is not merely within the human rights-related sector that advances are occurring. Organisations focusing on the rights of children, like the Noor Foundation for the Rights of the Child, have built up significant networks across the country that are strengthening (albeit slowly) awareness of the need to focus on protecting and advocating for the children across all levels of society.

Other organisations are focusing on doing community art and education, even in seemingly inhospitable locations like the heart of Sadr City. And hackers are increasingly taking a role in Baghdad’s and Iraq’s post-occupation life. Not as a politically revolutionary force, as they had in Tunis and/or Egypt, but within the framework of the old hacker’s credo in which young people both assume control and responsibility for their lives and use social media and computer technology more broadly as a tool of social freedom without being directly political.

Indeed, if there is one dynamic that seems to be emerging in the present circumstances in Iraq, it is that even as direct political activism can be fraught with peril for those operating outside official networks, social activism and creating new communities is laying the groundwork for a more robust level of political engagement by Iraq’s emerging generation, repeating a process that profoundly shaped Tunis’ and Egypt’s futures beginning about a decade ago. “We’re deliberately not political,” one hacktivist declared to me, “But I guess all of our work is, in the end, political.”

In Part 2 of this story, I explore how artists, educators and (h)ac(k)tivists are moving Iraq slowly to the kind of socio-political space in which fundamental change can occur. In the process they have managed to move beyond the anger and resentment towards the US and its allies, and all the destruction the last 10 years have wrought, and achieve a level of forgiveness and pragmatism – and through them, internal reconciliation – that forces those still viscerally angered about the war and committed to seeking retribution against its main perpetrators to consider how best to help Iraq move towards a democratic and sustainable future while also ensuring the process which enabled the 2003 invasion all it has produced cannot be repeated.

Mark LeVine is professor of Middle Eastern history at UC Irvine and distinguished visiting professor at the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies at Lund University in Sweden and the author of the forthcoming book about the revolutions in the Arab world, The Five Year Old Who Toppled a Pharaoh. His book, Heavy Metal Islam, which focused on ‘rock and resistance and the struggle for soul’ in the evolving music scene of the Middle East and North Africa, was published in 2008.

Follow him on Twitter: @culturejamming

You can follow the editor on Twitter: @nyktweets