A note on causes

If we want to make “another world” possible, we need communication that cuts through the grandstanding of politicians.

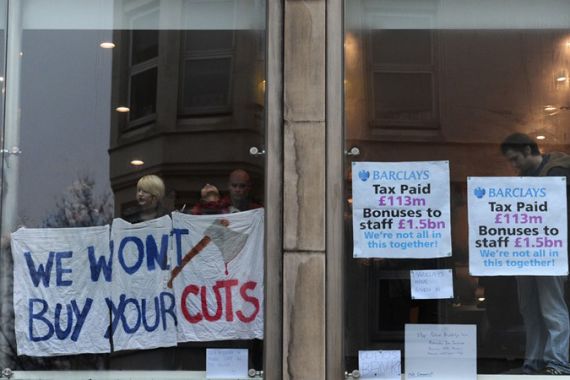

A little more than two years ago, I found myself outside a Vodafone store on Oxford Street. I’d read an article by Johann Hari about a group called UK Uncut. They were protesting against the cuts in public expenditure and calling for big companies to cover the costs of the recession. They were particularly annoyed about a deal that Vodafone had struck with the British tax authorities. Hence the Vodafone store.

Hari’s article and its insistence, that, in Margaret Mead’s words, “a small group of thoughtful people could change the world” persuaded me to join them on their next expedition. I wasn’t entirely sure what I was doing and I was vaguely worried that I was going to be arrested. But I was glad that someone had started to challenge a media-political system that wouldn’t, or couldn’t, pay attention to corporate tax avoidance.

In the two years since then, things have changed somewhat. By April 2012, the Conservative Chancellor George Osborne was telling the House of Commons that he regarded “tax evasion and – indeed, aggressive tax avoidance – as morally repugnant”. Large scale tax avoidance became an issue in the US Presidential elections after Vanity Fair reported on Mitt Romney’s tropical tax arrangements. This month Starbucks, Amazon, Google and Facebook have all faced criticism in the press over their use of offshore structures to minimise their tax liabilities.

Last week, the head of John Lewis, one of Britain’s most successful retailers told Jeff Randall of Sky that companies based in tax havens “will out-invest and ultimately out-trade us and that means there will not be the tax base in the UK”. Meanwhile, the Labour MP, Margaret Hodge, has made a name for herself as the scourge of the tax avoiders. She has called for a consumer boycott of companies that “immorally” avoid UK tax.

Public outrage

What’s missing is any sense of why this change has happened. Margaret Hodge and George Osborne are morally outraged. The major media are pursuing the issue aggressively. Parliament is being seen to act. This is presented as something that politicians and the major media do, on their own initiative. But it isn’t.

Politicians are saying what they are saying in response to a change in public attitudes. They know that people are thinking about tax avoidance and the offshore system that makes it possible. If they ignore it, they risk losing control of the agenda altogether. On the other hand, public outrage is something that can be reflected back to them in stirring rhetoric. The major media, which a few years ago dismissed tax avoidance as technical and boring, know that their readers care about it.

The public’s understanding of offshore changed because “a small group of thoughtful people” decided to do what they could to make an obscure issue obtrusive. That’s basically what UK Uncut is. It changed because a few journalists did what they could to increase awareness of the issue.

Richard Brooks’ articles in Private Eye drew attention to the Vodafone deal, for example. It changed because a few economists worked up ideas for tackling it. When the eminently practical head of John Lewis supported the idea that income “earned in a particular country” should be “taxed in that country” he wasn’t, in Keynes’ immortal phrase, in the grip “of some defunct economist”. Whether he knew it or not, he was proposing country-by-country reporting, an idea first set out by Richard Murphy, who is very much with us.

But you would struggle to find this out from most coverage of the issue. The politicians are seeking to take advantage, or minimise the policy implications, of a change in public understanding that they did little or nothing to achieve. If the Coalition hadn’t had UK Uncut and Occupy to contend with, they would have blamed those least able to answer back for the country’s economic crisis.

As it is, their attempts to demonise the vulnerable have to be balanced by references to the tax avoidance of the very rich. It must be very irritating for them. Still, they make the best of it and enact the fiction that change comes from well-meaning individuals in authority.

We are all encouraged to live out a similar lie in our own lives. We pretend that we aren’t influenced by others, that we are perfectly autonomous. Advertisers assure us that we are free thinkers and rebels. We graciously accept their praise and then do exactly what they tell us to do, like everyone else.

Democratic reform

We are constantly influencing one another. I turned up on Oxford Street two years back for a bunch of reasons. I was disappointed by the reception of my second book, The Return of the Public. I had invited the mainstream to consider what democratic reform of the media would look like, and what it might achieve. The invitation had been ignored or dismissed, so I figured I didn’t have much to lose.

My many detractors would say I had nothing else to do, and they would have a point. But Hari’s article was the clincher. He told me something was happening and persuaded me to join in. I am diminished if I don’t acknowledge that.

But saying so doesn’t do me any favours in the current communications system. I am meant to be an opinion former, after all. I am supposed to figure everything out for myself, and bring fire to mankind in a Promethean act of enlightenment. The deranged economy of attention rewards those who can persuade others that they were first to the scene, that it was all their idea. But heroic individualism is just another sales pitch.

At the moment, those who change things do so at considerable risk and receive scant reward. Many of the people involved in the UK Uncut protests were arrested a few months later on preposterous charges. Meanwhile, careerists and professional attention-seekers repackage the achievements of UK Uncut and groups like them as opportunities to display their fine sensibilities.

If we want to make another world possible, we need to create a system of communications that cuts through the grandstanding of politicians and other professionals of speech, that gives credit where credit is due, and breaks the current monopoly of prestige. We need, in other words, to understand the dynamics of political change, which brings us neatly round to the titanic achievement of my unjustly neglected second book.

Hey, I never said I was perfect.*

*This column was prompted in part by a Facebook post by Naomi Colvin.

Dan Hind is the author of two books, The Threat to Reason and The Return of the Public. His e-book, Maximum Republic, will be published later this month.

Follow him on Twitter: @danhind