The bomb, civilisation, and the human race

The possession and potential use of nuclear weapons by others is what currently justifies nuclear arsenals.

New York, NY – Not so many decades ago, many around the world hoped that the great civilisations and traditions of the non-European world would do better than the West when it came to nuclear weapons.

This was part of a larger idea that the formally colonised peoples would change the character of modern statecraft. They would lead the human race out of the murderous depths of imperialism, total war and genocide into which the West had taken it.

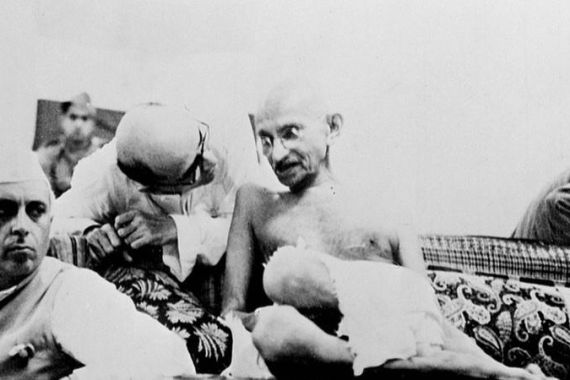

Mahatma Gandhi counselled non-violent resistance to nuclear bombardment. People should get out of their homes and look the pilots in the eye as best they could. With love and prayer, and without hatred for their killers above, they were to offer themselves willingly in sacrifice.

Aircrew were thus given the opportunity for redemption before bombs away, as Faisal Devji tells us in The Terrorist in Search of Humanity.

Clearly, Gandhi hadn’t banked on missiles.

He still would hope that the gesture of accepting death would be transformative for those who commit mass murder in pursuit of their political objectives. In the face of such willing sacrifice, the missile operators, their commanders and leaders, and the society form which they came, would decide to be better humans and build a better world.

They would come to regard others as humans equal to themselves, not as “collateral damage” or whatever other euphemism was used to justify killing.

So went one plan by which the traditions of the non-European world were to help remake international politics in humane ways.

What would Gandhi make of India today, armed to the teeth with the full panoply of modern destruction, including nuclear weapons aimed at Pakistani population centres? India is even building its own SSBN – a nuclear submarine that launches ballistic missiles.

China has an even larger arsenal. Japan could be a nuclear power overnight. North Korea already is.

One doesn’t need to only pick on states with Confucian, Buddhist and Hindu traditions – of course the political and military representatives of Islam and Israel behave no differently. Those that don’t have the bomb wish they did, while fearing and admiring those who do possess its awesome powers of destruction.

Logic of deterrence

One ready explanation for the global desire for nuclear weaponry is the seductive logic of deterrence. The invasion of Iraq and the air strikes on Libya were possible only because these powers lacked the bomb. A deliverable nuclear weapon promises survival and autonomy, because other countries will not dare to push you too far.

Such thinking is presumably behind Iran and Israel’s nuclear weapons programmes, and there is doubtless some truth to it.

All the same, such thinking equates security for oneself with the mass slaughter of others.

A moral philosopher once compared trying to achieve security with the bomb to the idea of preventing automobile accidents by tying live babies to car bumpers.

Nuclear weapons, it must be remembered, do not belong to familiar traditions of warfare. The instantaneous obliteration of thousands is not a military act even when the strike is aimed at a military target. As with the civilians practicing Gandhian non-violent resistance, the soldiers killed lack the opportunity to display their own virtues and practices of sacrifice.

For reasons such as these earlier generations of political leaders and thinkers came out in opposition to the bomb, demanding nuclear disarmament. Mass CND campaigns ensued in Western societies during the Cold War.

But nowadays, mass campaigns against global threats are waged in the name of the environment.

False security

It would seem that around the world, the whole human race has become comfortable with, even desirous of, the bomb. People everywhere seem to think that nuclear weapons will give them security.

They should think again.

For one thing, during the Cold War, the most likely route to nuclear war was that of accident. Even with the sophisticated command, control, communications and intelligence capabilities of the superpowers, the potential for an inadvertent nuclear exchange was unacceptably high.

One reason for this were pressures to “launch on warning” – to fire off one’s missiles on warning of an incoming enemy strike, a warning that might later prove to be false.

Given the ability of Western powers to wipe out the Iranian or North Korean or some other small country’s arsenal with conventional or nuclear strikes, such pressures will be all the more intense.

And that is without considering the rogue commander scenario, whereby an extremist officer opts for Armageddon by firing off his missiles. Such men were found in the United States Air Force during the Cold War, parodied by the base commander General Jack D Ripper in Dr Strangelove (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1964). General Curtis LeMay – who Ripper was modelled on – advocated obliterating Russia before the Soviets could develop a nuclear deterrent.

Do we all want to run these risks again, and in countries with much less robust traditions of civilian control of the military?

Retaliation and deterrence

But perhaps most worrying of all is the basic strategic position of a relatively small country trying to deter Western attacks with a few nuclear weapons. During the Cold War, the West sought to deter Soviet conventional superiority with nuclear weapons, as the West never had armies large enough to defeat the Soviets should they have invaded Western Europe.

The problem with this strategy is that nuclear escalation would only have invited a retaliatory strike in response. Nuclear attacks on Soviet forces or cities would have invited reply in kind, regardless of the conventional military situation.

So for example, a future Iranian leader facing conventional defeat by US and Israeli air strikes might decide to go nuclear. He might consider a US carrier battle group cooped up in the Persian Gulf as a “limited” and “military” target for his nuclear missiles. Amid the din of war, and the cries of his own wounded and dying people, he might fail to realise that such an attack would rain death on families across the US, who would lose brothers and sisters, fathers and mothers serving on those ships.

Turning Teheran into a nuclear waste site for the next century or two would only be the beginning of what any US president would do in reply to such an attack. Americans are a very violent people, and they do not take just one eye for each they lose. Equally, the US would realise that only a massive retaliation would serve to re-establish deterrence and dominance in other parts of the world.

This is the kind of “security” nuclear weapons buys you, if you have survived the sanctions, the international isolation, and the espionage the West visits on its enemies who try to acquire such weapons in the first place.

Ethical high ground

Against such outcomes, Gandhi’s ideas begin to look rather more realistic. They have the singular advantage of taking the ethical high ground, insisting that these weapons are not on a human scale, and that they must be done away with.

What might be achieved if the non-Western world were to forsake nuclear weapons on moral grounds? The possession and potential use of such weapons by others is what currently justifies Western nuclear arsenals.

Perhaps also, those in global civil society who spend their time protesting environmental doom might remember there are more immediate threats to the human race. They might consider joining the remaining CND activists in the West to finish the business of one of the world’s first mass protest movements.

For as of now, against the scourge of nuclear weapons, the human race has little more than the thin line of activists at places like the Faslane Peace Camp. They row out in their little dinghies to board British nuclear submarines in dangerous efforts to remind us all that these weapons are not worthy of human possession.

Tarak Barkawi is an Associate Professor in the Department of Politics, New School for Social Research.