Letters to a dictator

Mohammad Nourizad’s dissidence to the Iranian government comes in the form of admonishing, public letters.

|

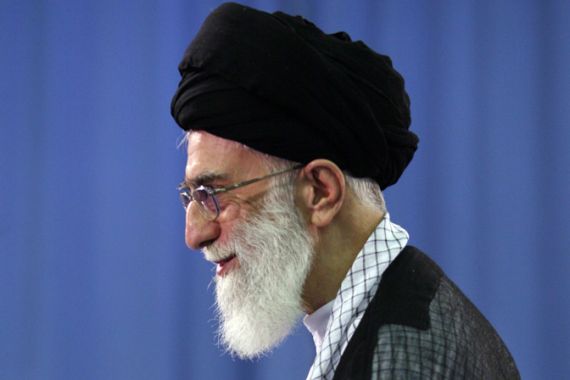

| In his letters, Mohammad Nourizad accused the “father” – Ayatollah Ali Khamenei – of being surrounded by corruption, and dared him to cease military rule to see what happens [EPA] |

Playa del Carmen, Mexico – Iranians around the globe these days are mesmerised in anticipation of the next public letter that Mohammad Nourizad will write to Ali Khamenei.

Much is happening in Iran these days, all under the radar of the Arab Spring and its cataclysmic consequences, whilst the US and its regional allies’ counter-revolutionary designs to halt and derail the Arab Spring laser-beams on the Iranian nuclear project. These events, exemplified by Nourizad’s letters and the public reaction to them, can only be understood in dialectical reciprocity with the world-historic events turning the region upside down, with the tsunami of the Arab revolts in particular, and with full recognition of the US-Israeli-Saudi attempts to alter their course to their respective benefits. The import of these events will remain entirely bewildering if left to the limited means of the nativist Iranian expat “opposition”, with their “Iran über alles” motto, or to those non-Iranians habitually severing the Arab uprisings from the democratic landscape of the region.

The letters of Mohammad Nourizad are now known and counted by their numbers – now only five, then 10, and by the end of 2011 they had amounted to no less than 15. These letters are written and published publicly to the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic, Ali Khamenei. The reaction of Iranians to these letters all comes together to mark a critical passage in contemporary Iranian political culture with ramifications for the region at large.

Nourizad publishes his letters initially in his website, and from there they go viral – millions of Iranians around the globe read them, jaws dropping in admiration of his courage, his diction, his tenacity. He pulls no punches.

|

“These letters are punctiliously polite, written in an exceedingly genteel diction, never crossing the boundaries of propriety – and then quickly they cut to the chase and expose the horrors of the Islamic Republic.“ – Hamid Dabashi |

These letters are punctiliously polite, written in an exceedingly genteel diction, never crossing the boundaries of propriety – and then quickly, they cut to the chase and expose the horrors of the Islamic Republic, its military and intelligence establishments, chapter and verse. For Mohammad Nourizad was, once, an insider.

Change of heart

Mohammad Nourizad (born on December 10, 1952) is an Iranian filmmaker and journalist. He studied engineering, but turned quickly to journalism and filmmaking, and put his talents at the service of the Islamic Republic. His journalistic career is tied with the arch-conservative daily Keyhan, where he was a columnist, making a name and reputation for himself as quite a prominent conservative supporter of Ayatollah Khamenei and a severe opponent of the Reform Movement of the late 1990s and early 2000s, as led by the two-term President Mohammad Khatami. But something happened to Nourizad in the aftermath of June 2009 presidential election – something that must have been brewing in him for a much longer time. When it emerged, it morphed into a principled critical judgment against the status quo – with a moral clarity impossible to ignore.

In three successive letters, written soon after the disputed presidential election of June 2009, Nourizad politely admonished Khamenei for taking sides with Ahmadinejad and not recognising presidential candidates Mir Hossein Musavi, Mehdi Karroubi, and the former president Mohammad Khatami as true friends and the true supporter of the Islamic Republic. He denounced the brutal crackdown of the people, and asked Khamenei to apologise to Iranians and call for a national reconciliation.

Soon after he published these letters to Khamenei, Nourizad was arrested in April 2010, sentenced and jailed. But from his jail, he continued to write letters, his tone even more adamant, his revelations even more damaging, but still polite, warning Khamenei that he had lost the confidence of the people, that Iranians were kept from revolting only by vicious and brutal military suppression and intimidation. He dared the Supreme Leader to cease the military rule and see what will happen.

While he was in jail, suffering in solitary confinement, Nourizad’s wife appealed for his release, as did scores of prominent Iranian filmmakers – all to no avail. Meanwhile, Nourizad was severely beaten in prison, in response to which he went on a hunger strike. His jailers asked him to repent and write to Khamenei for clemency. He did no such thing. He continued to write, until his pregnant daughter asked him to stop for her sake, which he did; his next public letter was to his daughter instead, continuing to expose the depth of corruption at the heart of the clerical, the military, and the security establishments of the Islamic Republic. He then asked other public figures to follow suit and write similarly polite, but admonitory letters to Khamenei, and some, such as the distinguished Iranian religious intellectual Abdolkarim Soroush, began to do so.

No response from Ayatollah Khamenei, but these letters became subjects of extensive public conversation among Iranians in and out of the country.

Upon being released from jail, Nourizad began making a film he had tentatively called Mahramaneh Bara ye Rahbarm (Confidentially For My Leader). The film was almost done when agents of the intelligence ministry invaded his home and confiscated it. A filmmaker of hitherto limited means and achievements who never made it to global or even national prominence, this film was to be his magnum opus – the visionary anger of a filmmaker whose best work ever has been taken away from him now informs the visionary precision of his diction when he writes his letters to his leader – whom he calls “father”.

The God who does not like the thieves

Direct public address has a peculiar power in Persian diction, otherwise prone to the anonymity of passive voice and indirection. Consider the fact that throughout his tumultuous days as the leading dissident voice in the aftermath of the June 2009 presidential election until his house arrest in February 2011, Mir Hossein Mousavi never ever in public addressed Ali Khamenei, and his addresses to him were always indirect. Nourizad’s letters are exactly the opposite of that anonymity of interlocutor. He speaks, directly, to the Leader, in public.

But that is not all. The direct tone of the letters gives them a distinct literary quality, akin to pages from a Latin American novel about a hideous dictator, omnipresent but absent, magical in its realist mode – real and unreal, deadly serious and yet politically frivolous, wherein the horizon crafted in between the lines of these letters, the ageing tyranny exposes itself. To be sure, these letters are not entirely new in modern Iranian political culture, and the late Ali Akbar Sa’idi Sirjani (1931-1994), a leading dissident, is now legendary for a powerful public letter of protest he once wrote to the same tyrant – and then paid for it with his life.

“In the Name of that God who does not Like Thieves”: that’s how he begins one of his most widely popular letters. He is always impeccably polite: “Greetings to Our Honoured Leader, His Highness Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.” In a letter he dedicated to “the thieves among the Intelligence forces and the thieves among the Pasdaran”, he first exonerates many among the Pasdaran whom he knows to be honest, dignified, never ever having stolen anything from the public wealth. He believes these forces have become increasing isolated, suffering in silence and isolation for what has happened to their Islamic revolution. Having made these exceptions, he is punctilious in accusing the Islamist military establishment of thievery.

He equally testifies that among the intelligence forces there are honest, polite and dignified people. But he then proceeds to say that these good ones are not in position of power and authority – and he accuses those who do have power and authority of stealing from what belongs to the public at large.

He informs Khamenei that fortunately the Supreme Leader’s home and the lives of his family members are immune from eavesdropping and surveillance, so he would not understand what it means for a phone to be tapped and a simple telephone conversation with the family members of a martyred friend can be taped and played back to him by way of intimidating interrogation.

| Talk to Al Jazeera – Mahmoud Ahmadinejad |

Nourizad also informs the Leader that fortunately in his house there are no hidden cameras that record even the most private aspects of a person’s life, “if he were to caress his wife or laugh heartily at her jokes”.

Nourizad is specific, speaking from personal pain: “Please have the recorded interrogation of the monster who was my interrogator with my young daughter so that your highness with your own noble ears can hear the words of this sexual and psychotic monster.” These intelligence agents and the Pasdaran have stolen the dignity of their respective organisations, which were supposed to be “Islamic”.

He accuses the agents of the ministry of intelligence of taking obscene pleasure from listening to the most private conversations between husband and wives or between strangers. No one is immune from these agents – they invade the sacrosanct peripheries of people’s privacy and use what they gather to intimidate and denigrate people.

Nourizad speaks of secrets that were stolen from the intelligence ministry so that Ahmadinejad could not use them against his enemies. “Ahmadinejad was disposable, and he knew it very well. He knew we had raised him so that with his psychopathology we could bury the Reform Movement. He knew he must pack well from this unrepeatable mission and fill his bags with these poor people’s money. Bags that could have gathered power for him.”

Nourizad assures the Leader he is willing to confront the thieves amongst the Pasdaran and the Intelligence ministry and both prove their thievery and plead with them to stop destroying the revolution for which they have all fought. He warns that the US and Israel are now plotting to do with Iran what they did with Iraq and Libya, get rid of some people and bring some other people to power and get the control of Iranian oil. He warns the Leader not to trust these Pasdaran or be fooled by them and thus invite confrontation with the US and Israel. That war, he warns, will enable these thieves to get rid of all their internal critics. He warns the leader that these thieves will drag Iran into war and then gather their belongings and run away. “Instead of relying on these Pasdars, rely on God and rely on this people – light is here, blessing is here, salvation is here.”

How to read public letters

Iranians’ reactions to Nourizad’s letters are varied. Some consider him heroic and trailblazing in upping the ante and exposing the horrors of the Islamic Republic to unprecedented dimensions – even more so than the presidential candidates’ debates during the June 2009 election, which in turn resulted in even more revelations about the atrocious history of the theocracy. Others are appreciative of these letters, but consider them useless and believe at this stage, opposition to the Islamic Republic needs more substance, organisation, leadership and purpose than mere words. Still others dismiss Nourizad altogether and consider him a devotee of the leader of the Islamic Republic that he always was, and offer the polite and supplicant tone of his letters as evidence. The entire regime is corrupt and incurable, they believe, and at top of it, the very person of Khamenei. So these letters are useless and in fact, diversionary.

There is also a cogent criticism (in Persian) that the sorts of letters that Nourizad and others like him write to the Supreme Leader, in fact, perpetuate the cult of heroes and heroism, reducing collective political actions at a mass societal level to individual acts of defiance. They give a false fetishism to the Green Movement and refuse to recognise that it has died out, that they amount to a nasty attempt at prolonging the Reformist discourse, and that above all, they pre-empt the rise of a “collective subjectivity” (mardom suzhegi) among the people.

In the absence of the mass rallies and the rise of the new media to reflect their evolving aspirations, people like Nourizad and others are being in fact, recycled and the discourses of Reform reproduced, so that the more radical expansion of the movement is pre-empted. Not just in Nourizad but also in others who follow his model and keep writing letters, there is an endemic verbosity, a discursive formalism, that in fact recycles a medieval prose and as such, categorically aloof from the realities of our time.

To be sure, these letters are indeed all of the Nasihat al-Muluk genre, a medieval mode of political tract in which a vizier or a wise man guides, warns and even admonishes the king for his own sake – so while in their sentiments they denounce tyranny, in their form they in fact exonerate the tyrant and thus, paradoxically exacerbate his tyranny. The form dismantles the content, the rhetoric its logic.

But democratic discourse is not made out of the thin air in the occulted dormitories of the blogosphere – it will have to be made of the substance of public discourse, and thus not just in what prominent people write, but in how people read and react to them. Mardom-Suzhegi is generated as much by the readers’ response (“intentio lectoris“) as by the writers’ intentions (“intentio auctoris“) – for the intention of the text (“intentio operis“) is a reality sui generis. Some key elements of a democratic diction are evident and hidden in these letters – so their sentiments and thoughts must be salvaged from their form. The facts revealed and the sentiments celebrated must be read in a transigent mode, while their form remains categorically intransigent, recalcitrant, and even retrograde. Their good politics and bad form demand a superior hermeneutics.

Without the destruction of that form through a liberating hermeneutics, all these wise and worthy words will have been in vain, a courageous exercise in futility.

But how can that form be overcome despite itself? There are always unanticipated consequences to any political act. Instead of writing to Khamenei, officers of the Pasdaran began writing directly to Nourizad, as did former leftist political prisoners who had suffered in the dungeons of the Islamic Republic in the 1980s – two entirely unanticipated consequence of Nourizad’s act. How about that? The fear that the Reformist agenda is recycling itself is defeatist, false, and a sad and unseemly case of ressentiment.

The democratic movement in Iran is alive and well. It was called Green yesterday; it might be called Red tomorrow. Those who criticise the Green Movement and consider it hijacked by the Reformists are in fact the ones chiefly responsible for fetishising an amorphous democratic uprising, out of their legitimate frustrations with the discredited Reformists.

You cannot blame or censure the Reformists for recycling their discourse and posing to come back to power, nor can you take issue with the religious intellectuals for writing in a museum style prose and diction reminiscent of medieval tracts and purpose, and as such entirely out of tune with reality. There is more than one way to skin a cat. They can write their letters in any manner and style they like – the question is what do you do with those historical facts thus generated precisely in the direction of crafting a new subjectivity liberated from not just the Reformist discourse but from the entire calamity called the Islamic Republic.

|

“A remarkable aspect of these letters … is that they are exquisite examples of constructing a character without ever seeing him.“ – Hamid Dabashi |

A remarkable aspect of these letters, evident in the fact that we never read any response to them by Ayatollah Khamenei, is that they are exquisite examples of constructing a character without ever seeing him, a feat most recently best achieved by Mohammad Nourizad’s fellow filmmaker Jafar Panahi in his celebrated film Badkonak-e Sefid (The White Balloon) (1995) where we meet a young boy, Ali/Mohsen Khalifi, on whose face and shirt we see the signs of violence, but never see anyone perpetrating that violence. All we hear (but never see) is the repeated admonitory and angry utterances of a father taking a bath in the basement of the young boy’s house, incessantly screaming at him asking for one thing or another. From that subterranean dungeon, the father screams loudly and torments his family, ordering his wife and children around, as the entire household lives in the echoes of his ceaseless commands – and we might also surmise that the signs of violence on the boy’s face and shirt might in fact be related to his father and his subterranean howling. Every one of Nourizad’s letters too are like the sequences of a film he is making not for but about his tyrant “father” – just like Panahi in the Badkonak-e Sefid constructing a character without ever seeing, or in this case hearing, him respond.

In a remarkable reverse projection of interlocution, these letters, in a far more enduring sense, might in fact be read not to Nourizad’s figurative “father” Ayatollah Khamenei but to his own real children, to his grandchild about to be born, and by extension to all other young Iranians suffering the calamity called an Islamic Republic, publicly apologising to them for a lifetime of commitment to “the God that failed”. In reading that failure, Nourizad and his “father” might be trapped, but their “children” are free:

Pride you took, pride you feel

Pride that you felt when you’d kneel…

It clouds all that you will know

Deceit, deceive

Decide just what you believe

I see faith in your eyes

Never you hear the discouraging lies

I hear faith in your cries

Broken is the promise, betrayal

The healing hand held back by the deepened nail

Follow the god that failed…

Hamid Dabashi is Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University in New York. His edited volume, Dreams of a Nation: On Palestinian Cinema was published by Verso in 2007. His forthcoming book, The Arab Spring: The End of Post-Colonialism, is scheduled for publication by Zed in April 2012.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.