Congo’s flawed but necessary election

The UN and EU’s decision not to send election monitors to DRC may place the country’s third poll since 1960 in jeopardy.

|

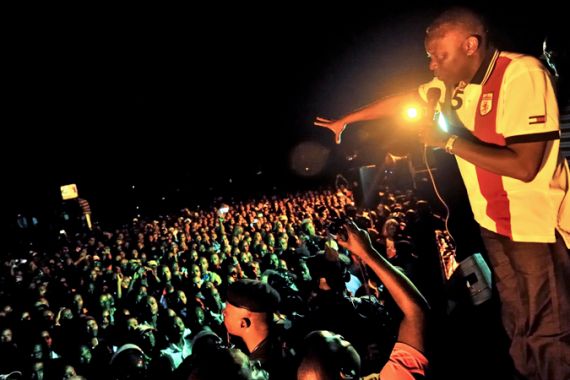

| Fewer election observers will be on hand to witness proceedings compared with the poll in 2006 [EPA] |

Fingers crossed, on November 28, 2011, millions of Congolese and Egyptians will go to the polls to elect the future presidents and parliaments of their respective countries. Expectedly, most of the world’s attention will be on post-Mubarak Egypt, a story which has captivated and inspired many around the world. This election marks a significant milestone in a popular revolution’s transition from a ruthless dictatorship to a military junta and, if all goes as hoped, onto the path towards a civilian democracy.

For Israel and her Western allies, this is important. The new pharaohs will have the power to reshape global power dynamics as Israel’s very existence depends on Egypt. Should the Muslim Brotherhood emerge as victors in the parliamentary race, one imagines the White House switchboard inundated with 3am calls to “nuke ’em all” from a paranoid President Binyamin Netanyahu.

From Cairo to Kinshasa

More than 2,000 miles south of Cairo is the Democratic Republic of Congo, a nation still reeling from Mobuto Sese Seko’s repressive dictatorship and a devastating war whose unpriceable cost includes around 5 million dead, 3.4 million refugees, at least tens of thousands raped and more than 22,000 of the world’s largest concentration of hippopotamuses killed for bush-meat and love potions.

The third election since the country declared independence from the Belgians in June 1960, this vote signifies an important historic moment in the political development of the DRC as an African Republic. That it’s the second poll since 2006 is a positive sign that, despite ongoing conflict in the eastern provinces, the DRC is steadily emerging from the ruins of war.

Voting, as a consistent national tradition, moves towards creating a lasting democracy in post-war Congo and establishes the electoral process as a functional institution of the state. The same is true for Egypt. After 31 years of Hosni Mubarak’s repressive and rigged elections and ten months of Field Marshall Tantawi’s unelected military junta, this is potentially the first democratic referendum in a long, long time.

A place frequently overlooked in a year where people power has become the dominant global narrative, the DRC’s India-style mass democracy, with almost 19,000 candidates competing for 500 parliamentary seats, makes the case for greater media interest in the heart of Africa. Contrary to the media machine’s production of mass protest as the current single most important form of people power, elections are another.

Critical connections remain to be made between mass protest in the Arab World, global #occupy movements, economic demonstrations and worldwide national elections – as the good and bad rumblings of functional democracies. The year 2011 has seen almost 20 elections in Africa, far more than any other continent, but fewer than half have caught the media’s attention for long.

Congo may not be as exhilarating a story as #occupy, but the news of more than 32 million registered voters making their second democratic choice in 51 years needs to be in the spotlight.

The front-runners are Joseph Kabila, son and political heir of the late Laurent Kabila, and Etienne Tshisikedi, of the main opposition. A Chinese-trained Major-General who inherited the presidency at 29 after his father’s assassination, Kabila is widely expected to win the vote with Tshisekedi, the longest standing opposition figure in Congolese politics, taking second place.

Hailed as the “Mandela of the Congo” by his supporters in the central and western provinces, ironically, 78-year-old Tshisekedi served as prime minister during Mobuto’s brutal regime. Although he later resigned and eventually formed his own party in 1982, his current campaign has been punctuated by pompous proclamations and violent rhetoric.

Earlier this month in a telephone interview with pro-Tshisekedi station, Radio Lisanga TV, he confidently boasted: “We don’t need to wait for the elections. In a democracy, whoever has the power is the majority of the people. Therefore, from this day on I am the Head of State of the DRC.” He further went on to give a 48-hour ultimatum to the Kabila government to release scores of arrested opposition supporters, or he would order people to “mobilise everywhere and set free the supporters and other opponents and break all the prisons”.

Calling from Johannesburg, South Africa, Tshisekedi’s threats amounted to little more than a desperate last-minute campaign strategy; talk big and dangerous to get attention. And get attention it did. Shortly after the interview, the Minister of Communications ordered the shutdown of Radio Lisanga TV as part of “precautionary measures” against possible violence. Though the state may have legitimate fears of pro-violent campaigning, it’s also never had a strong tolerance for freedom of speech.

In Kabila’s DRC, candidates compete in a political climate where it is against the law to insult the head of state or even question his nationality, as one member of the Movement of Liberation of the Congo discovered when imprisoned for allegedly being in possession of a journal claiming Kabila was not Congolese.

Arbitrary arrests and beatings of pro-opposition civilians are also not uncommon and the increasing number of clashes between opposition protesters, Kabila’s supporters and state security forces have raised serious concerns among local and international activist and aid organisations.

Someone say war crimes?

Unlike the previous election of 2006 that was monitored by more than 2,000 international observers, a lower figure of around 600 observers – mainly provided by the AU and EU – are overseeing this national poll. The UN is not sending any monitors because, apparently it believes, “other organisations are better equipped than MONUSCO [UN Mission in Congo] to conduct election monitoring and observation”.

Congo researcher and author, Jason Stearns, suggests this was a UN compromise; in order to renew its mission in July, MONUSCO had to play ball with a government which has long desired the swift withdrawal of 19,000 peacekeepers from the DRC. So instead, the UN has busied itself with sounding the alarm bell over Congo’s electoral unpreparedness and escalating pre-election violence. A UN report to the Security Council shows that in January and February alone, there were 65 incidences of election-related rape just in South Kivu province.

Other rights groups have also drawn attention to a disturbing loophole in the DRC’s electoral law. It allows accused war criminals to run for a seat and this year, there are two accused candidates. Despite the small matter of his imprisonment and pending court date at The Hague, 2006 presidential hopeful Jean-Pierre Bemba is trying his luck again.

Charged with murders and rapes committed by his militia men in Central African Republic between 2002 and 2003, Bemba denies any wrongdoing. His lawyers remain upbeat about the trial and have applied for a special temporary reprieve from prison so he can bid for the presidency. But with days to go before D-Day, it’s not going to happen.

Another war crimes candidate is Ntabo Ntaberi Sheka, standing for a National Assembly seat. As leader of the Mai Mai fighters who fought against Rwandan-backed rebels and government forces in the Kivu provinces, Sheka is charged with being partly responsible for the rapes of 387 men, women and children.

Although an arrest warrant was issued in January this year, Sheka remains at large and eligible to run for office. Congolese law prevents those prosecuted for specific serious crimes, from running for public office, except National Assembly candidates. A special immunity is automatically granted.

Even though Kabila has the executive authority to withdraw Sheka’s protection, he hasn’t. Worse still, the trial has begun with only one of eight accused appearing in court. This is one of many colossal government failures which, in the Congo’s volatile conflict and post-conflict environment, inadvertently creates the conditions for sexual violence to continue without reprimand.

Congo fatigue?

It might be standard for some to remain unmoved by “yet another Congo story”, but now is not the time to suffer Congo fatigue. It’s a contagious condition known to numb the senses or create feelings of despondency when people and governments grow weary of funding, reading or writing about “the troubled heart of Africa”.

The reduced number of monitors for this election is telling. Had a letter, allegedly written and signed by a quartet of Congo-fatigued EU parliamentarians, successfully convinced Catherine Ashton, the EU Human Rights Commissioner, there would be no EU election monitors because the union’s recession-hit member states can’t afford to send any. The patchiness of international support makes it all the more important for journalists to witness and document the electoral process.

Moulded in the template of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, an eighteenth century explorer novel, today’s Congo is often seen as a dysfunctional jungle state of horrific mass rape, endless conflict, incurable tropical diseases and blood coltan. These largely Western constructions rarely go beyond the singular, stigmatising tropes of Conrad’s savagery to understand the complexities of post-conflict nation building. As the Congolese prepare for another flawed, but necessary ballot, it’s clear the creation of alternate, multiple Congo narratives is possible.

Tendai Marima (PhD) is an independent researcher and correspondent currently based in Southern Africa. Follow her on Twitter: @KonWomyn

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.