Warfare and limits: a losing battle?

Nationalism, the dehumanisation of killing, and the frustration of asymmetrical war erode traditional limits on warfare.

|

|

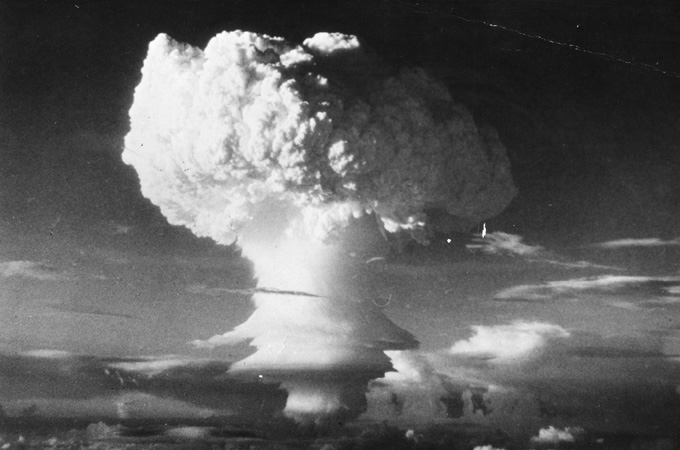

The collapse of the Cold War deterrence system has made nuclear warfare more likely; however, there is little outcry against nuclear weapons today [GALLO/GETTY] |

Dangerous pressures are pushing international warfare in the direction of the absolute, imperiling the future of mankind. Undoubtedly, the foremost of these pressures is the emergence, use, retention, and proliferation of nuclear weapons, as well as the development of biological and chemical weapons of mass destruction.

Since Hiroshima and Nagasaki there have been several close calls involving heightened dangers of nuclear war, especially during the 45 years of Cold War rivalry. None of these was more frightening than the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, when it took Soviet willingness to reverse their decision to deploy missiles in Cuba to avert a slide into catastrophic nuclear war.

To entrust such weaponry to the vagaries of political leadership and the whims of governmental institutions seems like a Mount Everest of human folly. Yet there is little outcry against nuclear weapons today, despite the collapse of the deterrence rationale that seemed to make reliance on the weaponry somewhat plausible during the decades of confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States. Even under Cold War conditions, deterrence was seen by peace activists as a form of geopolitical insanity widely known by the descriptive acronym “MAD”, short for “Mutually Assured Destruction”.

Underneath the tendency of powerful governments to develop whatever weapons and tactics technology can provide are the fragmented political identities of a world divided into sovereign political actors. The inhabitants of these states of greatly varying size, capabilities, vulnerabilities, cultural and political traditions have long been indoctrinated to approve blindly of the actions of their own state. The idolatrous eyes of nationalism treat the extermination of an enemy as an acceptable goal if necessary for national security, and even desirable, if it is seen as furthering national ambitions.

Beyond this, defending the security of one’s own state is viewed as an unconditional prerogative, vindicating even a suicidal reliance on nuclear weaponry. The ideology of nationalism, nurturing the values of unquestioning patriotism and militarism in the modern West, have led to an orientation that can be described as secular fundamentalism, embodying imperial worldviews, however dysfunctional, given the risks and limits associated with continuing to seek desired political ends by relying on military superiority. The crime of treason reinforces these absolutist claims of the secular state by disallowing citizens of democratic states any right to claim conscience, law, and belief in support of their deviant behaviour.

‘Militarist frustration’ since WWII

Any objective study of international history will show that the militarily superior side has rarely prevailed in an armed conflict since the end of World War II unless it has also been able to command moral and legal legitimacy. The political failure of the colonial powers despite their military dominance provide many bloody illustrations of this recent trend toward militarist frustration, starting in the middle of the 20th century.

Because of entrenched bureaucratic and economic interests (the “military-industrial-media complex”), the evidence of the decline of hard-power geopolitics has been ignored. As a result, dysfunctional military solutions for conflicts continue to be relied upon in the West, especially by the United States, and costly and futile recourses to war are repeated over and over without lessons of restraint being learned. Experience, which might provide a rational limit on militarism, has been neglected; instead, old habits persist.

Another check on the excesses of warfare is supposedly provided by the inhibiting role of conscience, the ethical component of the human sensibility, that is supposed to be a hallmark of citizenship in liberal democracies. This sentiment was vividly expressed in a Bertolt Brecht poem, “A German War Primer”:

|

General, your bomber is powerful |

A driver is both a human cost, and maybe a brake on excess, as Brecht suggests a few lines later:

|

General, man is very useful |

Of course, military training and discipline are dedicated to overcoming this defect, especially when complemented with nationalist ideologies. International humanitarian law has vainly been trying to impose limits on combat behaviour in wars, but almost always yields in practice to considerations of “military necessity”.

The Nuremberg Trials decided that “superior orders” were no excuse if war crimes were committed, a breakthrough in establishing responsibility for adhering to law in relation to war, but flawed by its character as “victors’ justice”. Although beset by double standards, this Nuremberg tradition of imposing individual accountability for political and military leaders has persisted, and has recently been revived through the establishment of the International Criminal Court in 2002.

In the nuclear age, this process of dehumanising the military machine went further because the stakes were so high. I recall visiting the headquarters of the Strategic Air Command (SAC) at the height of the Cold War. SAC was responsible for the missile force that then targeted many cities in the Soviet Union. What struck me at the time was the seeming technocratic sensibility exhibited by those entrusted with operating the computers that would fire the missiles.

This amoral posture contrasted with the ideological zeal of the commanding generals who would give the orders to annihilate millions of civilians at distant locations. I was told at the time that the lower-ranked technical personnel had been tested to ensure that moral scruples would not interfere with their readiness to follow orders.

I found this mix of politically and morally driven commanders and amoral subordinates a most disturbing mix at the time, and still do, although I have not been invited back to SAC to see whether similar conditions now prevail. I suspect that they do, considering the differing requirements of the two roles. This view seems confirmed by the enthusiasm expressed for carrying on the “war on terror” in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. Although my remarks here are confined to the United States, I would suppose they apply to other major governmental bureaucracies dealing with national security and war/peace issues.

Use of drones dehumanises war

Now, new technological innovations in warfare are underlining these concerns. American reliance on drone attacks in Afghanistan (and elsewhere) removes the human altogether from the war theater, except in the geographically remote roles of programmer and strategic planner. And even then, reliance on algorithms for targeting removes any shred of personal responsibility. When mistakes are made, and innocent civilians are killed, it is treated as an unfortunate anomaly.

The tragic event is deprived of its human quality by being labeled “collateral damage”, and a formal apology is usually made. But nevertheless, the practice goes on: the US is investing heavily in more and better drones for future wars. Eliminating the presence of human soldiers from the battlefield is a chilling development: historically, the fact that war put soldiers’ lives at risk forced citizens to think about whether a war was morally right, or worth fighting. The anti-war sentiments of American soldiers in Vietnam exerted a powerful influence that helped over time finally to bring the war to an end.

Ultimately, what is at stake is the human spirit, which at the moment is being squeezed to near-death by technological momentum, corporate greed, militarism, and secular fundamentalism. The ultra-sophistication of the new weaponry and the accompanying military tactics create a new divide in the military sphere, giving rise to an era of virtually “casualty-free” and one-sided wars where the devastation and victimisation are shifted almost totally to the technologically inferior side. Examples include The Gulf War of 1991, the Kosovo War of 1999, and the Gaza Attacks of 2008-09. In the background, however, is the persisting threat of a use of nuclear weapons either by a state or an extremist non-state actor that could in a flash change this ratio of comparative vulnerability.

This web of historical forces continues to entrap major political actors in the world, and dims hopes for a sustainable future, even without taking into account the growing threat of climate change. Scenarios of future cyber warfare are also part of this evolving capacity to destroy distant societies without any human interaction. The cumulative effect of these developments threatens to make irrelevant the moral compass that alone provides acceptable guidance for a sustainable political future. Because international institutions remain too weak to provide global governance, reason and prudence remain the best hope to guide human destiny.

Richard Falk is Albert G. Milbank Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University and Research Professor in Global and International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He has authored and edited numerous publications spanning a period of five decades, most recently editing the volume International Law and the Third World: Reshaping Justice (Routledge, 2008) and Achieving Human Rights (Routledge 2009).

He is Chair of the Board, Nuclear Age Peace Foundation and Director, Global Climate Change Project, UCSB. He is currently serving the fourth year of a six year term as a United Nations Special Rapporteur on human rights in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.