Iran’s Khatami: The sound and the fury

Mohammad Khatami’s recent conciliatory stance towards the Iranian government has alienated former supporters.

|

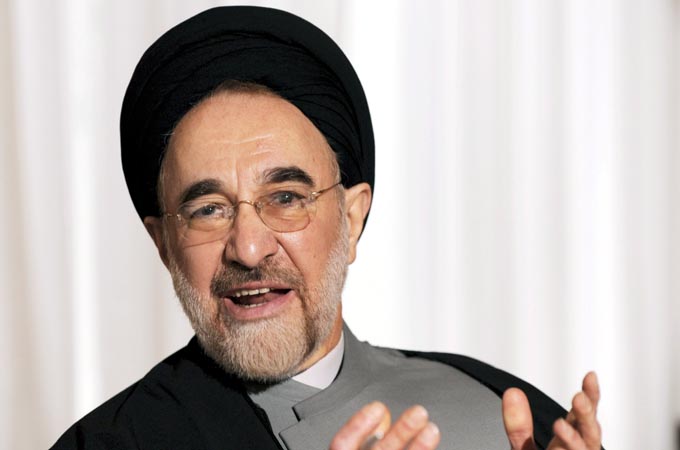

| Former president Mohammad Khatami has manipulated the opposition Green Movement since the arrest of its leaders [EPA] |

The world might be distracted by the dramatic events in Syria, Libya, or even Yemen, but the pushing and pulling, jostling and shoving, kicking and elbowing for the post-Ahmadinejad Islamic Republic is well underway.

Ahmadinejad has done his services to the ruling Ayatollah, and will be disposed of momentarily. His grand illusion that he can actually have a face off with the Supreme Leader and determine who – his choice is a close aide named Rahim Mashaei – is to succeed him is being dashed off rudely with the combined security, intelligence, military, and clerical forces that staged him against the Green Movement and will now escort him to the exit door.

This exit – now well underway – is happening in a larger context. More than two years into the rise of the Green Movement in Iran and half a year of astounding developments in the Arab world, the Islamic Republic of Iran is juggling its domestic affairs to be able to cope with the tremor of regional earthquakes – and suddenly, at the centre of it all, one finds, yet again, Mohammad Khatami, the two-time Reformist president (1997-2001 and 2001-2005) who was once thought to be the Iranian Mikhail Gorbachev. It was not meant to be.

As Ahmadinejad is being made redundant, Khatami may prove, yet again, to be useful – at least to the ruling regime.

The smiling Seyyed

Mohammad Khatami gently glided into the modern Iranian, and by extension, the global scene, during the presidential election of 1997, when his landslide victory became the symbolic indicator of a massively based Reformist Movement that was poised either to break the back or else immunise the Islamist theocracy to any meaningful changes. It did not break its back.

Glasnost, Perestroika: It is hard to believe now, but at the time people were comparing Mohammad Khatami to Mikhail Gorbachev – and thus by extension saw the vista of an “opening” and a “restructuring” that would end the Islamic Republic very much the same way that Gorbachev had ended the Soviet Union.

It did not happen that way. Khatami managed, quite to the contrary, to give a sudden respectability to the beleaguered Islamic Republic. Masses of millions of young Iranians had poured into their streets campaigning and voting for him. He had outmanoeuvred the expatriate opposition, out-staged the banished left, and caught the ruling conservatives off guard. He was gentle in his demeanour – smiling, cheerful, liberal, feminine. “Seyyed Khandan” people call him to this day: The Smiling Seyyed.

Under Khatami’s two-term presidency, the Reformist Movement had one slogan, translated into one strategy: “pressure from below, negotiation from above”. The pressure from below had nothing to do with the Reformists.

The pressure was predicated on structural deficiencies of the Islamic Republic itself, some of it, in fact, the results of the neoliberal economics that Khatami, and before him Hashemi Rafsanjani, had unleashed with catastrophic consequences for the most vulnerable segments of society. The Reformists were trying to be the political beneficiaries of widespread dissatisfaction they were in fact in part responsible for generating.

To the degree that this pressure “from below” had political venues to express itself within an Islamist theocracy, it was an expression of the general health and maturity of a democratic will, which the Reformists had no moral or intellectual wherewithal to read. And as for “negotiation from above”, the Reformists had failed miserably to negotiate any enduring measure of civil liberties, or curtail the arbitrary rule of the fraternity club of clerics. In 1997, with more than 80 per cent reported voter turnout, and some 70 per cent of which cast their ballots for him, Iranians had given Khatami a mandate, with which he could have in fact saved his beloved Islamic Republic and secured and institutionalised certain civil liberties. He lacked the courage, the conviction, or the imagination to do any such thing.

Whatever his two-term presidency achieved was lost overnight when, in the course of the presidential election of 2005, the vastly more populist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad banked on some 15 million poor and impoverished Iranian voters who had been left out of Hashemi Rafsanjani post-war economic liberalisation, and could not care less about Khatami’s cosmetic social reforms. What was left from that period was the terrible, and terribly elitist, metaphor of below (for the democratic will of the people) and above (for the jaundiced abuse of that will to achieve no enduring civil liberties).

Once a tragedy, twice a farce

Khatami resumed a lethargic political life after his two-term presidency – keeping himself busy trying to get “civilisations” to have a dialogue with each other, as a kind of a gentle doppelgänger of Samuel Huntington. The Reformist Movement made a miserable attempt at a comeback in the presidential election of 2005 and their candidate, a decent but dull and entirely uninspiring professor of pediatrics named Mostafa Moeen, lost to the vastly more conniving and populist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

It was not until the presidential election of 2009 that Mohammad Khatami resurfaced on the Iranian political scene. He initially announced his own candidacy to run for a third (non-consecutive) term, which caused the bloodthirsty Rasputin of the Islamic Republic, the editor-in-chief of the Kayhan daily, Hossein Shariatmadari, to threaten his life in very thinly disguised language.

But Khatami stayed put until Mir Hossein Mousavi came out of a two-decade-old semi-seclusion from active political life and declared his intention to run for office. Khatami withdrew his candidacy in favour of Mousavi and put his weight behind the former prime minister, actively campaigning for him, and instrumental in helping create a vastly enthusiastic presidential election. There is a picture of Khatami campaigning for Mousavi in Isfahan that is now one of the iconic registers of what would later be code-named “The Green Movement”.

One can and must remember that without Khatami’s enthusiastic support, Mousavi would have never generated the joy and enthusiasm that came his way. Khatami gathered the fervour of his vast popular base enthusiastically and happily handed it over to Mousavi. Twenty years out of the active political scene, Mousavi was not a household name to the younger generation of Iranians. Khatami was their idol. Khatami coached, guided, blessed, and delivered Mousavi to his own base. Mousavi supporters should never forget that.

In the tumultuous aftermath of the June 2009 presidential election, Khatami was a critical force in sustaining the initial, and historically most momentous, rise of the Green Movement. The movement was given a renewed lease and legitimacy in the aftermath of the Arab Spring, when, on February 14, 2011, we saw the very last attempt at a mass rally – brutally suppressed by the ruling theocracy. Mousavi, Karroubi and their spouses were all put under house arrest, after a lynch mob of the “Majlis deputies” stormed the podium screaming “Death to Mousavi, death to Karroubi”, and even “Death to Khatami”.

The effective incarceration of Mousavi and Karroubi since mid-February 2011 left Khatami alone as one of the three most vocal and trusted figures publically committed to democratic reform, with various degrees of radical dispositions. Mousavi was by far the most radical of the three, still very much committed to the constitution of the Islamic Republic, to be sure, but using the post-electoral crisis to open up a whole new chapter in public discourse about civil liberties, democratic principles, rule of law, and forgotten or betrayed ideals of the revolution. Karroubi was equally courageous, if less systematic and purposeful.

Khatami was the most mild and the most liberal of the three, still believing in what his camp used to call conquering the democratic fronts “one trench at a time” [“sangar beh sangar“]. Even though, it is imperative to remember today that Khatami was among the very first to use the term “velvet coup/kudeta-ye makhmalin” in describing the result and aftermath of the June 2009 presidential election.

The three worked together with a tacit harmony – seeing, hearing, and saying things in a manner that complemented each other: just like the Three Wise Monkeys of the Tosho-gu shrine – Mizaru, Kikazaru and Iwazaru. With Mousavi and Karroubi out of the public eye, Khatami was just like Mizaru, closing his eyes to see no evil, but what he heard and what he said did not benefit from the wisdom of Kikazaru and Iwazaru, who could see and hear better than he.

This is when he should have remained silent – but he did not, could not resist the temptation. Bad move.

The storm began on May 17, 2011, when, towards the end of a long and rambling speech to a group of Iran-Iraq war veterans Mohammad Khatami said:

| “If an act of tyranny has been perpetrated, and it has been, we should all forgive and look towards the future, and if an act of tyranny has been committed against the regime and the leadership, for the sake of posterity it [too] must be forgiven. The people will also forgive the tyranny that has been visited upon them and upon its children, and we will then all face a better future. We should of course all work very hard, collaborate, and prepare the way for a future in which we will create a healthy, safe, and free future in which we will secure people’s rights.” |

Khatami’s speech to the war veterans was soon followed by some leading and highly respected Reformists – such as Mostafa Tajzadeh and Mohammed Nourizad – endorsing Khatami’s position to enumerate certain conditions under which the Reformists would go back to politics and join the next parliamentary election. One such leading Reformist, Ali Mazru’i, even spoke of a “rapprochement/mosaleheh” between the Green Movement and certain factions of the Principalists.

A sudden rush of severe and even violent criticism followed. Leading democracy activists in and out of Iran began denouncing Khatami for plotting to bypass the Green Movement and go back to resume where the Reform Movement had left off. One such critic, Mojtaba Vahedi, now outside Iran as a spokesperson of Mahdi Karroubi, went so far as accusing Khatami of “betraying” the cause of liberty in Iran. He concluded with a bravura: “I am proud that I am no longer a Reformist.” The reformist activists now turned their anger against Vahedi. Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mahdi Karroubi remained under house arrest.

The Islamic Republic was getting ready to manufacture yet another electoral farce, and as Mohammad Khatami and his Reformist lieutenants were lining up, their detractors were now retorting back, to provide their services. As Arash Judaki, one such leading critic, put it, the evident rift between Ahmadinejad and Khamenei had offered the Reformists the chance to try to re-enter the dominant politics, and accused them of “opportunism”.

Others were much harsher. Some even began, and rightly so, to question the whole false binary between “reform and revolution”, dismantling “the ideological myths” of the Green Movement, accusing the Reformists, again rightly so, of using the prospect of “violence” and “revolution” as a goblin (“lulu-khorkhoreh“) to frighten “the naughty child” of the democratic uprising.

To be sure, Mohammad Khatami still remains enormously popular with a vast base of Green Movement activists – especially those who call themselves “Melli-Mazhabi/Nationalist-Religious”. They insist that the Green Movement is in fact the result, the continuation, of the Reformist Movement of the 1990s, which they categorically attribute to Khatami’s ideas and aspirations.

This generation, having projected their own courage, imagination, and achievements to Khatami’s pleasant poise and smiling disposition, is wary of any criticism coming his way. They cling to every word, every preposition, every comma of his phrasing, yet again projecting their own goodwill and conviction onto him. They are parsing not just words, prepositions, conditional clauses, and commas – they are following him as he splits the Red Sea to have and hold Khatami as the vista of their hopes, the sight of their salvation.

They dismiss any and all criticism of Khatami as “radical”, “idealist”, “violent”, or “delusional”. They are particularly dismissive of people who criticize Khatami from “outside” Iran. You are not here, you do not understand, you live a peaceful and comfortable life, they tell their detractors. We must be pragmatic, they insist.

Be that as it may, the negative reactions to Khatami’s words were so harsh that he soon realized what a terrible faux pas he had made asking for forgiveness from the ruling Sultan – and quickly retracted and corrected course. “Making peace does not mean to disregard the demands”, he said in a speech on June 11, 2011, less than a month after his slip about “forgiveness”. “How could one sell short people’s rights?”

The making of a triumvirate

Ultimately the problem is not why Khatami is so weak, spineless, and accommodating to power – projecting his moral and intellectual limitations as “wisdom” or “pragmatism”. The problem is that he is all of these things from a position of weakness, facing a tyrannous monstrosity, and in the absence of any more radical positions within the general contour of the current political atmosphere.

In these circumstances, Mousavi’s forced silence is in fact infinitely nobler and more eloquent than Khatami’s weakling pleadings for forgiveness from a tyrant. Under other circumstances, at the very least, when Mousavi, Karroubi, Zahra Rahnavard and other exiled voices can freely say and articulate their positions, Khatami’s conciliatory voice is not only perfectly legitimate but in fact even necessary, as important and crucial as anyone else’s.

But when the ruling tyranny has silenced everyone – by assassination, imprisonment, torture, house arrest, exile, fear and intimidation, impoverishment, et cetera – Khatami’s wobbly pleading is so pathetic because it is not stated from a position of free, fair, and democratic encounter with other, more or even less radical, voices. This regime has mutilated the Iranian political culture, does not even have the decency of allowing for a dignified funeral of an aging dissident, and its official thugs attack mourners and cause the death of his daughter – and to this regime and under these circumstances, Khatami says “if” people have done you wrong and been tyrannous towards you, you should forgive them.

Never in the entire history of Shiaism have tyrannised people been so robbed of their moral authority and the sacrosanct term of zolm been so brutally stolen from them, abused and applied to a tyrant. No amount of contextualisation, gloss, or appeals to pragmatism can whitewash that astoundingly immoral utterance.

Democratic movements are restoratives, consistent and committed to their historic course, while giving birth to new leaders and iconic representations. Left to their own history in a brutal and repressive regime, none of the current representatives of the democratic uprising in Iran would have had an iota of legitimacy. They are all, without a single exception but to varying degrees, implicated in the criminal records of the Islamic Republic.

But democratic movements are not vindictive, they are restorative. The fact is that not only Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mahdi Karroubi but Mohammad Khatami as well had been given a new lease on a new political life by virtue of the Green Movement. Without this resumed democratic uprising, none of these figures had any widespread credibility that would cross ideological or territorial barriers.

Neither Khatami, nor Mousavi and Karroubi are the leaders of this democratic movement – they are its momentary custodians. They have all received their credibility by the degree to which they are closer to the heartbeat of this movement – most of all Mir Hossein Mousavi, and precisely because he was closest to the pulse of his people. Khatami was, in fact, furthest removed from the fast pace of that pulse – but nevertheless he was (and still remains) a force, a factor, a measure. When he was with the other two, he was a unifying force.

Now, left to his own devices, he is a deeply divisive and fractious voice. Whoever had Mousavi and Karroubi arrested (Khamenei et al) and let Khatami free to say whatever he wanted to say, he knew what he was doing – he knew that, deaf and dumb to the realities around him, he would cover his own eyes not to see evil and become a stooge in the danse macabre that is the Islamic Republic. “Carrying the stamp of this one defect … doth his noble substance often doubt”. Instead of misreading Samuel Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations, he should find someone in his entourage to do a half-decent translation of this eternal wisdom for him (Hamlet Act 1, Scene 4). It will do him (and the rest of us) good:

|

So oft it chances in particular men That for some vicious mole of nature in them – As in their birth (wherein they are not guilty, Since nature cannot choose his origin), By the o’ergrowth of some complexion, Oft breaking down the pales and forts of reason, Or by some habit that too much o’er leavens The form of plausive manners – that these men, Carrying, I say, the stamp of one defect, Being nature’s livery or fortune’s star, Their virtues else (be they as pure as grace, As infinite as man may undergo) Shall in the general censure take corruption From that particular fault. The dram of evil Doth all the noble substance often doubt To his own scandal. |

Hamid Dabashi is the Hagop Kevorkian Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Literature at Columbia University.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.