What is Obama’s Afghanistan plan?

Obama’s “way forward” with respect to Afghanistan leaves many baffled and questioning his motives.

|

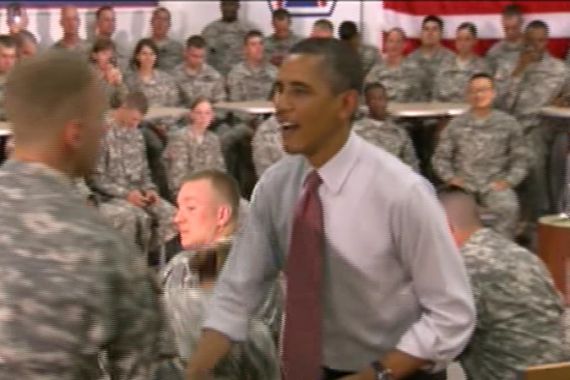

| Obama intends to withdraw 10,000 US troops by the end of this year, and to complete the withdrawal of some 30,000 troops by September 2012 [GALLO/GETTY] |

US President Barack Obama’s speech from the White House on June 22 concerning the “way forward” in Afghanistan struck many as highly unusual. Though billed in advance as a policy pronouncement, it was in fact much more like a campaign speech. Like any campaign speech, it was a complicate mixture of political expediency, vain hope, and actual intention, delivered in a manner intended to make it hard to distinguish one strand from another.

In fact, when we disaggregate it, the president’s speech of June 24 is best understood as two speeches. One was intended to present the administration’s policy in Afghanistan as a principled, consistently-applied, well-thought-out program which has been systematically executed since the start of the current administration, and which is meeting with success. This was the policy speech, and I regret to say that it was a blatant and intentional lie. The other speech, the campaign speech, was an exercise in persuasion, designed to provide the rationale for what President Obama actually intends: a partial retreat from the burdens of international leadership and, most particularly, a substantial withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Weighty promises

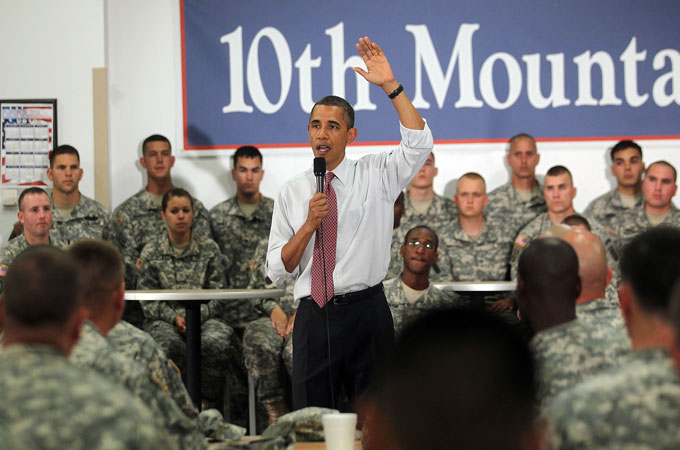

Both of last Wednesday’s speeches are best understood as a continuation of a similarly bifurcated message delivered by Obama some 19 months before. On December 1, 2009, the president traveled to the US Military Academy at West Point to deliver a much-anticipated address, the capstone of an exhaustive four-month review of US policy in Afghanistan, and the second such review conducted in the first year of his presidency. The reason for the re-review, and therefore for the speech itself, was that Obama had made a rather fundamental error. He had committed himself the previous March to a highly ambitious program of comprehensive counter-insurgency warfare and nation-building in Afghanistan, an effort which he claimed was required by core US national security interests, but for which he had grossly underestimated the potential costs. Invidiously comparing his intended program at the beginning of his administration with that of the Bush years, Obama indicated that, unlike his Iraq-addled predecessor, he would commit the attention and the resources required for success in Afghanistan.

Only later, after his appointment of Gen. Stanley McChrystal as the new Afghan commander, did the president learn what his promises entailed. According to the military leadership, a successful counterinsurgency campaign in Afghanistan would require an additional 40,000 troops, above and beyond the nearly 70,000 to which Obama had already expanded the force – and even then, they advised, success could not be assured. What we learned definitively last Wednesday, but which Obama would not openly admit at the time, was that this was far more than the president had bargained on. Given the scale of the costs and the risks, Obama wanted no part of such a continuing Afghan commitment. But that is not what he said at West Point. Instead, the US president delivered a speech which confounded almost everyone. Giving no indication that he intended a fundamental shift in strategy, the US president announced the “surge” commitment of an additional 33,000 troops, nearly all that his commanders had requested. Those who favored the comprehensive counter-insurgency strategy championed by Generals McChrystal and Petraeus were pleased.

But there were also myriad indirect indications in that speech that the President’s heart was no longer in it. No longer did the President promise the “defeat” of the Taliban; instead, he would “deny their ability to overthrow the government,” while buying time in hopes that the Afghan National Army could be expanded at break-neck speed to pick up where the Americans left off. No longer was he promising the resources necessary for success. Instead, he firmly rejected both “open-ended escalation” and the very idea of “a nation-building project of up to a decade.” “As President,” he said, “I refuse to set goals that go beyond our responsibilities, our means, or our interests.”

A radically different course

Observers therefore should not have been as surprised as they were when, at the end of the speech, as though it had been an afterthought, the president mildly noted that the US withdrawal from Afghanistan would begin in the summer of 2011. In subsequent response to panicky fears that the President was heading for the exit, both administration spokesmen and senior uniformed military provided immediate reassurances that any withdrawal would be “conditions-based”.

For some, such assurances were probably mendacious; for others, especially the military, such assurances were a form of wishful thinking. But the continuation of his West Point speech delivered last Wednesday makes it unmistakably clear: President Obama is set on a radically different course in Afghanistan than the one he promised at the outset.

Of course, the president would have us believe that the steady drawdown he plans is based on the success of the surge he launched in December 2009. Nothing, in fact, could be further from the truth. Yes, U.S. troops have predictably made considerable inroads against the Taliban in the South; but the President also has to know that these gains cannot be maintained, as the Afghan government lacks either the military or governing capacity to sustain them.

This will not matter, however: Irrespective of the conditions, the president intends to withdraw 10,000 US troops by the end of this year, and to complete the withdrawal of the full surge complement of 33,000 by September of 2012 – not coincidentally, some two months before presidential elections. He has also stated that the US withdrawal will continue steadily until 2014, when the Afghan government will assume full “responsibility” – note he did not say “capacity” – for its own security. As usual, one must seek subtle clues in the president’s words to intuit his true intentions, but he also made it clear on Wednesday that his goals for Afghanistan have been substantially reduced. He summed it up himself: “The goal that we seek is achievable, and can be expressed simply: No safe haven….” The method for achieving that goal will likewise be simple: sustaining a partnership with Afghanistan “that ensures that we will be able to continue targeting terrorists and supporting a sovereign Afghan government.” Translation? What the president is saying is that while the US cannot defeat the Taliban and will not try, it will sustain sufficient military presence in Afghanistan, including after 2014, as to preclude the Taliban from toppling the government in Kabul, and to retain the special forces capacity to strike at terrorist safe havens on either side of the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. In other words, if the prime US goal is to prevent the reestablishment of an uncontested terrorist safe haven in South Asia, President Obama will ensure that such safe havens as will inevitably persist will at least be contested.

What is the plan?

Make no mistake: A fundamental shift in US strategy in Afghanistan is long overdue. The US-led counter-insurgency campaign and the plan to build both a highly centralised Afghan state and an unsustainably large Afghan Army have never made any sense, and have been doomed to fail from the outset. But if Obama had determined on a radically different course in December, 2009, why did he allow the military to launch a southern counter-insurgency campaign which he had no intention of sustaining? How can he justify to American mothers and fathers the killing and maiming of their sons is such a doomed effort, to say nothing of the Afghan civilians killed and the government officials assassinated by the Taliban?

From all accounts, the US military intends to continue with an American-led strategy against the Taliban through summer of 2012. Does the administration really believe that this will force the Taliban to accept a lasting political settlement, knowing as it does that American power in the region will steadily decline? Absent a new, clearly-articulated strategy, which the president will only hint at while continuing to promote the politically-expedient illusion that the old strategy is succeeding, American commanders on the ground will be forced to improvise, adapting their approach and their operational priorities to the dwindling resources at their disposal. Under those circumstances, what assurances can we have that any coherent alternative strategy will result on the ground?

Further, not having addressed the fundamental issues of political decentralisation and the proper respective roles of a sustainable Afghan army and of traditional regional power-brokers, how does the administration hope to promote and support an alternative Afghan-led solution to the country’s challenges? What assurances can anyone have that at the end of the US drawdown, there will be a sufficient presence to sustain a responsible Afghan policy and contribute to a viable political solution? We do not know, because President Obama will not tell us.

Paying the price

Finally, the president has again piously insisted that Pakistan “expand its participation in securing a more peaceful future” for the region, and work with the US to “root out the cancer of violent extremism”. America, he intoned, will “insist that [Pakistan] keeps its commitments”.

Why, one wonders, with America rushing for the exits and providing scant assurances for what will follow, should Pakistan take great risks in support of US policy? Given that all indications are that Afghan insurgents will soon be reinforcing their presence in that country, beyond the effective reach of the Pakistan Army, why would Pakistan seek to antagonise them and motivate them to support extremists who directly threaten the Pakistani state?

In short, President Obama, in pursuing a needed course correction in Afghanistan, is doing it in a characteristically misleading and indirect manner, confusing everyone in the process, and undermining both the regional relationships and the internal coherence necessary for success. The president’s approach might make sense in terms of domestic politics; but this is no way for a superpower to conduct business. For such malfeasance, there is a price to be paid, and it is not the politicians who will pay it.

Robert Grenier was the CIA’s chief of station in Islamabad, Pakistan, from 1999 to 2002. He was also the director of the CIA’s counter-terrorism centre.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.