Africa’s cascade of Internet censorship

As governments fear popular protest movements, filtering has been initiated in Ethiopia, Uganda, Ivory Coast and beyond.

|

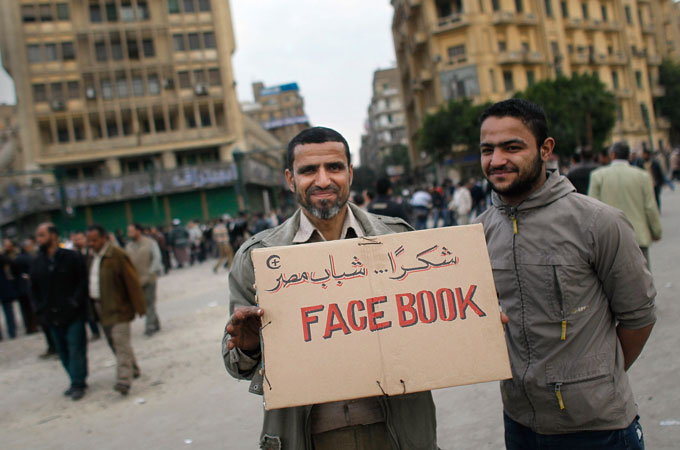

| Africa continues to struggle with Internet access, representing only 5.6 per cent of the total global online population [GALLO/GETTY] |

Despite much attention paid to Egypt and Libya’s Internet shutdowns, Tunisia’s pervasive Internet filtering, and Morocco’s arrests of bloggers, little attention has been given to Internet censorship issues throughout the rest of the African continent. Events in recent weeks, however, have brought the region’s online troubles into sharp focus.

In Ethiopia, government filtering of websites has long been common practice. Despite an Internet penetration rate of only 0.5 per cent, the Ethiopian government blocks a range of political opposition websites, as well as independent news sites reporting on the country and the sites of a few human rights organizations. Ethiopia’s Internet infrastructure is state-owned, leaving control of it entirely at the hands of the government.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsCould shipping containers be the answer to Ghana’s housing crisis?

Are Chinese electric vehicles taking over the world?

First pig kidney in a human: Is this the future of transplants?

Recently, on World Press Freedom Day, Ethiopian officials hijacked an event sponsored by UNESCO, removing independent journalists from the lineup and installing government-approved reporters in their place, as the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported. At the same time, the government lifted the ban on a variety of sites normally blocked under the country’s filtering regime. Ostensibly, the lift occured in the face of the UNESCO event’s theme: new media and the Internet.

Despite the unblocking – likely temporary, if history is any indicator – Ethiopia continues to be one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s worst offenders when it comes to Internet freedom.

Just-in-time blocking in Uganda

As protests have spread like wildfire across the Middle East and North Africa, “just-in-time” blocking of websites (a phenomenon wherein sites are blocked temporarily around a protest or other event) has become increasingly common. On April 14, Uganda’s Communications Commission (UCC) quietly ordered ISPs to block Facebook and Twitter for 24 hours in light of a Walk to Work protest against spiralling food and fuel prices in the country.

According to Uganda’s Daily Monitor, a letter from the UCC ordered social networking sites Facebook and Twitter to be shut down for security reasons, stating:

| We have received complaints from security that there is [a] need to minimise the use of the media that may escalate violence to the public in respect of the ongoing situation relating to walk-to-work mainly by the opposition in the country … You are therefore required to block the use of Facebook and Twitter for 24 hours as of now; that is, April 14, at 3:30pm to eliminate the connection and sharing of information that incites the public. |

When pressed, the office stated that the letter was unnecessary and that no ban would take place. However, some Ugandans reported the sites temporarily inaccessible on Uganda Telecom.

Though the sites remain accessible, Ugandan Commissioner of Police Andrew Kaweesi has called cyberactivism a Western phenomenon, stating that “governments need to come up with an enabling law that guards against misuse of communication networks to protect social values and national identity,” and called for regulation of online publications.

Though most of the continent has been free from Internet filtering, with increased access comes increased control. Burundi, which is not known to block websites, arrested the editor of an online news site in 2010, and in April 2011 the prosecutor in the case sought a life sentence. Such methods aren’t uncommon: Egypt’s internet is largely free as well, yet dozens of bloggers have been arrested over the years.

Practices vary by country. For example, some nations, such as Ivory Coast, have moved to enact filtering. A March 24, directive from the Ivory Coast Telecommunications Agency called for the ban of anti-Gbagbo websites (no word on whether that initiative has since fallen through).

Sudan has left the Internet largely unfettered, preferring instead to use social networking sites to track down protesters. According to a blog post by researcher Patrick Meier, the Sudanese government reportedly set up a group calling for protest, drawing thousands of activists to join. Many of those who attended the street protests were met by police and arrested for their participation.

Despite strides in recent years, the African continent continues to struggle with Internet access, lagging behind the rest of the world with only 5.6 per cent of the total global online population. Nevertheless, recent initiatives, including one from Google, promise to develop greater access to the Internet.

But as access to the Internet increases across the African continent, there will undoubtedly be a cost, as there has been in so many other parts of the world: online freedom.

Jillian York is Director for International Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation in San Francisco. She writes a regular column for Al Jazeera focusing on free expression and Internet freedom. She also writes for and is on the Board of Directors of Global Voices Online.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.