Matilda: A tale of Tsar-crossed lovers

Controversy has surrounded a state-sponsored film about the romance between Tsar Nicholas II and a teenage ballerina.

Оn Monday, the Russian film Matilda finally premiered in St Petersburg’s Marinski Theatre amid heavy security. Its release, originally scheduled for autumn 2016, had been postponed three times. Over the past year, the film has faced a string of controversies culminating in threats against cinemas and acts of violence that have left some Russian observers puzzled.

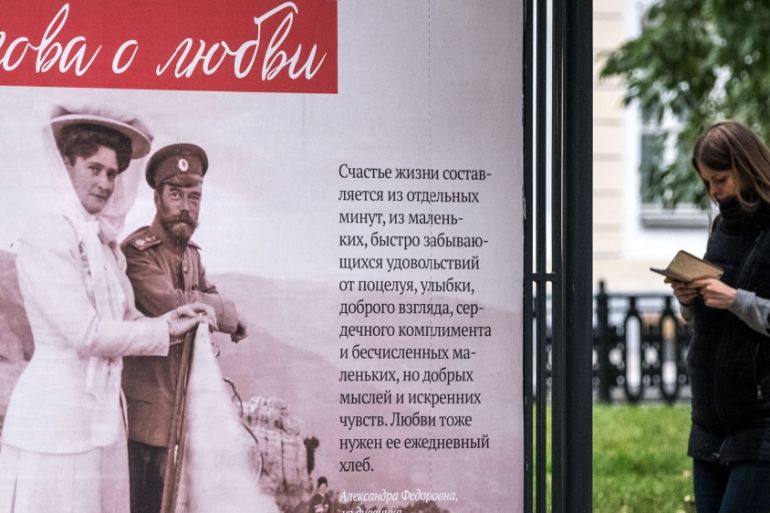

The film tells the story of the romance between prima ballerina Matilda Kshesinskaya and the last Russian tsar, Nicholas II. With a budget of $25m, the participation of some 2,000 extras, the use of 7,000 costumes and scenes shot in the Kremlin and lavish royal palaces, Matilda was supposed to be a simple state-sponsored romantic drama showing off the splendour of Tsarist Russia. Instead, it faced a campaign calling for it to be banned.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

In the months after the trailer for the film was released in April 2016, various conservative voices denounced it on social media, pointing out that Nicholas II, who along with his family was executed by Bolsheviks in 1918, was canonised by the Russian Orthodox Church in 2000.

Natalia Poklonskaya’s campaign against Matilda

But it was when Natalia Poklonskaya, a member of the State Duma, took the case to the General Prosecutor’s Office in early November 2016 that the controversy grew.

Poklonskaya first made international headlines in 2014 when at age 34 she was appointed prosecutor of Crimea. The video of the press conference where she announced her appointment went viral and turned her into an anime heroine. In September 2016, she took a seat in the Duma as a member of the ruling United Russia Party. Poklonskaya’s main accusation against the film was that it “insults believers’ feelings”, which is a criminal offence in Russia, according to a law passed in 2013.

As her campaign against Matilda gained momentum, Alexei Uchitel, its director, sought legal help.

“The first statements of Poklonskaya evoked laughter because, from the point of view of logic, they looked really bizarre,” said lawyer Konstantin Dobrinin, who started working on Uchitel’s case in early December 2016.

Poklonskaya was persistent. Within a year she filed 43 complaints against the film, despite receiving rejections from the prosecution each time. She wrote posts opposing it on her personal account on the Russian social media network VKontakte, including ones that accused German actor Lars Eidinger, who plays Nicholas II in the film, of Satanism.

Poklonskaya has received support from various public figures, including Chechen President Ramazan Kadyrov, Orthodox Church clerics, and the head of the public council of Russia’s culture ministry.

In February, a little known Christian organisation called Christian State started sending threatening letters to cinemas warning them against screening Matilda. According to Dobrinin, the authorities did not take action against the threats.

In the following months, the government also stayed away from the controversy. When asked about the film in June, Russian President Vladimir Putin said he would not get involved but that he knew Uchitel as a “patriotic and talented” man. Uchitel’s protests to the authorities and Dobrinin’s complaint against Poklonskaya to the ethics committee of the State Duma did not yield any results.

Then on August 31, Molotov cocktails were thrown at the building where Uchitel’s studio is located in St Petersburg. A week later a man drove a truck full of explosive substances into a cinema in the city of Ekaterinburg (1,800km east of the capital, Moscow). On September 11, two cars parked under Dobrinin’s office in Moscow were set on fire; notes left at the scene of the arson said “Burning for Matilda”. Immediately after, two cinema chains announced that they would not be screening Matilda; Russia’s state-owned Channel One had also said that it would not be showing the film. The two leading actors, Eidinger and Michalina Olszanska, who played Matilda, declared that they would not be attending its premiere in October.

According to Dobrinin, Poklonskaya’s campaign and claims that the film is blasphemous and insulting to believers encouraged “psychologically unstable” people to carry out the attacks.

Poklonskaya, who did not respond to requests for comment from Al Jazeera, did publicly condemn the violent acts, but continued with her campaign.

Just two days after the last attack, Culture Minister Vladimir Medinsky released a statement, denouncing the violence: “I’ve been accused of being too conservative, and as a conservative, I would like to say that such [violent] activists discredit the state’s cultural policies and the Church.”

The statement also said that there was no reason for the ministry to deny Matilda a screening permit.

Within a week of Medinsky’s statement, the police had arrested three members of the Christian State organisation, including Alexander Kalinin, its leader.

State support for conservative values

But what puzzled some observers is that a campaign against a state-sponsored film was allowed to go on for so long. The film’s budget was part public money which came from a state cinema fund and part private – with some alleging that that too came from the Kremlin via an offshore company.

“There is still no clear answer [why this happened]. It all looks weird,” says Mikhail Fishman, a Russian journalist and presenter on independent Russian TV channel Rain.

“What was weird about the whole thing was that [Uchitel] is part of the system, […] he’s connected to the state, funded by the state, or by groups really close to the state. Poklonskaya is also part of the state system. And she starts attacking, it’s like one attacking the other,” explains Fishman.

He also says he is puzzled by the involvement of the Christian State group because he had never heard of the organisation prior to the threats it issued against the film.

Ivan Otrakovsky, the leader of another Orthodox political organisation “Svetlaya Rus”, told Al Jazeera that he knew Kalinin well, as he was active in church and monastery gatherings and events. He says he does not follow his violent means but agreed that the film should be banned and those who made it excommunicated from the Church.

“These liberal forces, they detest the Оrthodox and the Muslims, I call them Satanists – those who purposefully destroy the Russian soul. And I’m convinced it’s this type of people who are behind the film, Matilda,” says Otrakovsky.

According to Fishman, the Matilda controversy is linked the growing state support for conservative values. Conservative attacks on cultural events, arts and books have happened before in Russia, but never on this scale, he says.

“Russia is a hub of traditional values, that is [Putin’s] point since he came back to power in 2012 […] He uses it as a tool,” Fishman says.

But, in his opinion, Putin probably has nothing to do with the Matilda controversy. He thinks it might be the result of a clash of factions within the ruling elite, one of them possibly using Poklonskaya as a front.

In mid-September, Russian journalist and commentator Yury Saprikin wrote that the campaign against Matilda might be used to rally support for the planned creation of a new conservative party or public organisation.

But regardless of whether there is indeed a clash within the Kremlin’s walls or a new political project emerging, the controversy surrounding the film made it the most anticipated Russian motion picture. Russia’s most popular film website Kinopoisk gave it an anticipation rating of 86 percent, the highest among upcoming Russian films. Its premiere at the Marinksy Theatre was sold out.

Follow Mariya Petkova on Twitter: @mkpetkova