Ear Hustle: Prison podcast tells of life in San Quentin

Recorded in the historic San Quentin State Prison, the new Ear Hustle podcast paints a human image of life in lockup.

A bunk bed with mattresses. A toilet and sink side by side. Two lockers. A television. A handful of permitted appliances. Pictures of family, friends and loved ones pinned up on the walls. Six cubic feet of personal belongings. And two men.

This is the claustrophobic scene inside most of the drab, four-by-nine feet (1.2 metres by 2.7 metres) cells in the infamous San Quentin State Prison, a medium security institution in northern California.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUK returns looted Ghana artefacts on loan after 150 years

Fire engulfs iconic stock exchange building in Denmark’s Copenhagen

Inside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

In this environment – where San Quentin prisoner Emil says “nothing is safe” – who you end up with as a cellmate is of colossal importance.

Although people in US prisons most often are not allowed to choose their cellmates, they are sometimes afforded the opportunity to apply for an exception based on compatibility.

Emil, who has been in prison for two decades, was lucky enough to choose as a cellmate his brother, Eddie, in another prison a few years back.

“The first few nights were great,” Emil says, but things soured quickly. His brother is a devout Seven-Day Adventist who doesn’t watch television on Saturdays.

The two were at each other’s necks by the first weekend. “I thought he was just trying to convert me,” Emil recalls, explaining that it later came out that the theme songs of the soap operas he watched triggered Eddie’s memories of the domestic violence his mother endured when they were children.

The brothers found themselves fighting over headphones, the odour of their antiperspirants, smoking cigarettes in the cell and every other seemingly benign matter.

They quickly applied to swap cellmates with others.

|

|

Ear hustle

This story and others like it are recollected and broadcast on Ear Hustle, a new podcast supported by Radiotopia and produced by Earlonne Woods and Antwan Williams, inmates at San Quentin, and Nigel Poor, a Bay Area visual artist.

Their anecdotes shed light on the day-to-day hardships prisoners deal with inside San Quentin State Prison, the oldest prison in California and home to the state’s only death row for male inmates.

Ear Hustle, which is prison lingo for eavesdropping, is enlightening, sad and often chock-full of humour.

And most importantly, because most news consumers rarely hear about the situation behind bars unless there is a mass hunger strike or riots, the podcast informs listeners of aspects of life neglected in mainstream media coverage and popular culture.

READ MORE: Is the US failing its inmates?

For Poor, a 54-year-old who has worked as a visual artist for 30 years and is a professor at Cal State University – Sacramento, the connection to San Quentin started in 2011, when she started working on news-driven radio stories with prisoners for a closed-circuit station inside the prison.

A little more than a year ago, Poor teamed up with Williams and Woods to start Ear Hustle with the hope of telling first-person narrative stories from inside prison for an outside audience.

Challenging stereotypes

“The goal is, first of all, to put a human face on people who are incarcerated and to get the outside world think about who is in prison in a more three-dimensional, complicated way,” she tells Al Jazeera.

Explaining that “basically everything that happens outside also goes on inside [prisons]”, Poor says they kicked off the first episode with an exploration of choosing a cellmate because “everyone can relate to that”.

Poor, Williams and Woods hope to communicate a more accurate and nuanced picture of prison life that moves beyond the stereotypes and inaccuracies they say characterise popular television programmes like Orange is the New Black and Prison Break.

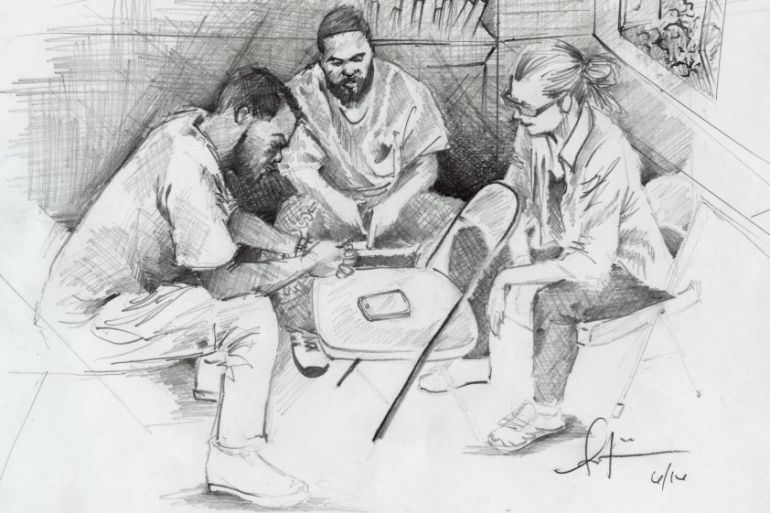

![Antwan, left, Nigel, centre, and Earlonne, right, hope to inspire a desire for prison reform [Eddie Herena/Courtesy of Ear Hustle]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/728bedb83d084b7b85cabfb7d4902a43_18.jpeg)

And for Poor, her own assumptions have been challenged along the way. “Before I’d gone into prison, all my ideas were based on movies and TV and not-so-good journalism,” she recalls.

“The first assumption is that it’s always dangerous, that people aren’t educated, that people are just thinking about what they can do to get one over on the administration,” she explains, “but, of course, there are all sorts of people in prison.”

READ MORE: Is this the end of prison for profit in the US?

Other episodes explore race dynamics inside the institution and others allow San Quentin prisoners to tell their own stories in their own words.

Some episodes are quirkier. In the third episode – “Looking Out” – a 40-year-old prisoner nicknamed Rauch talks about the various pets he has had while in lockup: snails, cockroaches, swallows, hamsters and toads, among others.

“I do not call animals pets,” Rauch says. “I call them critters. I hang out with these guys or girls. They’re friends. I don’t own them.”

The episode navigates between bouts of humour and recollections of Rauch’s tragic upbringing oscillating between foster homes and homelessness. It goes on to examine how people in San Quentin nurture – “looking out” – their companions and support one another.

Challenges

Poor says the podcast’s reception has been “overwhelmingly” positive. On June 30, Ear Hustle was ranked number one on the iTunes US podcasts chart.

Among the criticisms she has encountered are accusations that Ear Hustle isn’t political enough, which she describes as “strange” because “anything you do inside a prison is inherently political”.

In a country where prison reform is among the most debated topics in the political discourse, Poor, Williams and Wood hope that compelling stories that humanise the incarcerated can contribute to changing the public perception of prison life and thus highlight the need for change.

The production of Ear Hustle hasn’t been without its challenges, either. Although she says the prison administration has been generally supportive of the project, navigating the red tape of coming and going has been difficult at times.

Once she is with Woods and Williams inside San Quentin, there is no access to internet. After leaving, they are unable to communicate via telephone or email and must wait until her next visit.

![Earlonne and Nigel interview an inmate in the prison yard [Eddie Herena/Courtesy of Ear Hustle]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/263684b283a4401bb20dc10c203f95ad_18.jpeg)

READ MORE: The American prison factory

“Once I leave, that wall really does come up,” she says, adding that they generally work for 10-to-12 hours a day. “And if there’s a lockdown, we’re incommunicado. So, we have to be super prepared and thorough.”

The prison’s communications department also must vet the episodes before they can be released.

Despite the challenges, Poor, Wood and Williams hope to continue expanding the project. They plan to have Ear Hustle broadcast in some 34 prisons across California and others in England and Scotland.

Emphasising that Ear Hustle is not a journalistic project so much as an artistic one, Poor says reporters often forget that inmates are at constant risk of paying the price for potentially provocative or inaccurate information they publish once they’ve left the prison.

“People seem to forget that you are really speaking to people whose voices have been [stripped from them], and you have to respect that. There is a responsibility for us to tell stories that are accurate,” she concludes.

“They’re [the inmates] very aware of how often the press comes in and tries to tell their stories for them, and it’s a battle cry for them to be able to tell their own stories.”

Follow Patrick Strickland on Twitter: @P_Strickland_

|

|