Saving Syria: Is international law the answer?

As the war enters its seventh year, the prospect of achieving a peaceful solution is becoming increasingly difficult.

One year ago, Staffan de Mistura, the United Nations diplomat tasked with finding a peaceful solution to the war in Syria, described the subject of political transition as “the mother of all issues” in negotiations between the Syrian government and the opposition.

Achieving political transition in the country has long been considered the most challenging part of ongoing diplomatic efforts to end the war that started in 2011 as a peaceful uprising demanding Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to step down, amid widespread uprisings in the Arab world.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPalestinian Prisoner’s Day: How many are still in Israeli detention?

‘Mama we’re dying’: Only able to hear her kids in Gaza in their final days

Europe pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

It quickly turned into a civil war between government forces and armed opposition groups made up of army defectors and ordinary civilians, after Assad’s government responded to the protests with force.

READ MORE: The ‘slow-motion slaughter’ of Syrian civilians

UN efforts have been hampered by the two sides’ lack of willingness to compromise on their position with regards to political transition. The Syrian government has systematically refused to entertain any prospect of a transition that entails the removal of Assad, while, for the opposition, this step remains the only option for peace.

Three weeks ago, de Mistura brought Syria’s warring sides to the negotiating table in the Swiss city, Geneva, for the third time over the course of the war, to discuss ways of ending the ongoing cycle of bloodshed that has killed close to half a million people.

De Mistura promised another round of negotiations later this month to implement United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2254, which serves as a framework for a political transition in Syria.

But as Syria marks six years of war, the likelihood of achieving a peaceful, diplomatic solution to the war, rather than a military one, is becoming increasingly difficult.

Facts on the ground

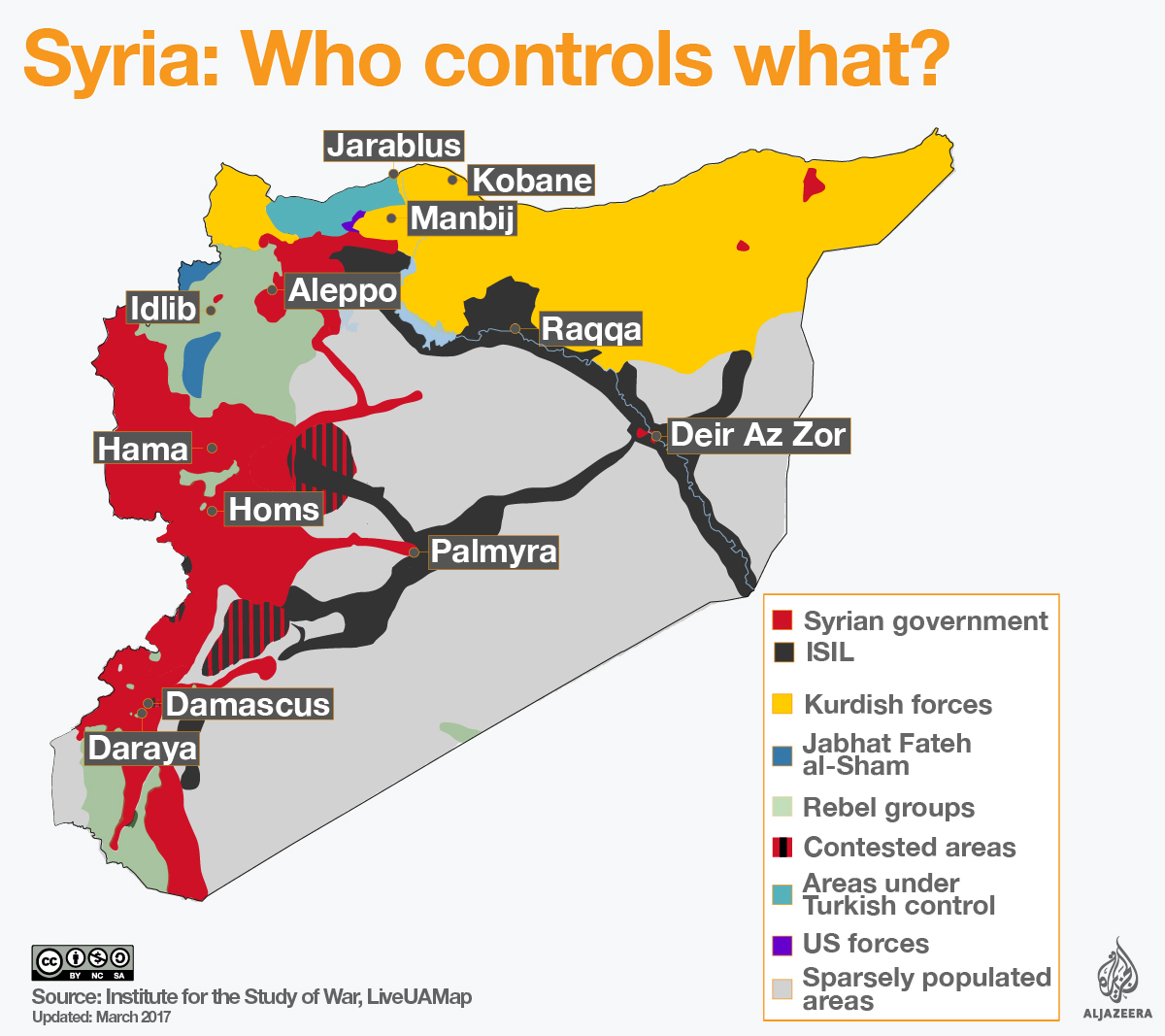

Russia’s military intervention in late September 2015 drastically changed the balance of power on the ground, placing Assad’s forces firmly in control, with the help of Iran-backed fighters and the Lebanese Hezbollah armed group.

Last December, the armed opposition, trained and supplied by the United States, Turkey, and several Gulf states, was dealt its worst defeat of the war when it lost its stronghold of eastern Aleppo to government forces and Russian air bombardment.

“The Syrian people did not lose militarily to the government. The Syrian people lost militarily to the second strongest army in the world – the Russian army,” Zaki Lababidi, vice president of the Washington, DC-based Syrian-American Council, told Al Jazeera in Geneva, during the last round of talks.

“Russia came in; they used their air force, they used their navy, ballistic missiles, and they put ground troops. This is how Aleppo was destroyed,” said Lababidi, who was present in Geneva to advise the opposition delegation.

|

|

Fighting both the Syrian government, on one front, and hardline armed groups including the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant ( ISIL, also known as ISIS) and Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (JFS) on the other, the opposition has steadily lost significant territory and leverage in Syria, which analysts say minimises the chance for a peaceful solution.

“The regime refused to discuss the prospect of a meaningful political transition even when it appeared to be losing ground militarily, so there is no prospect of it choosing to do so now that it has momentum. Nor will the opposition concede its demand for such a transition – including Assad’s departure – despite their weakening military hand,” Noah Bonsey, Syria analyst for the Brussels-based International Crisis Group think-tank, told Al Jazeera.

What next?

Though aware of their shortcomings on the battlefield, the Syrian opposition, which consists of both political and military branches, believes that international law lies in their favour. “For us, attending negotiations was never about the balance of power on the ground, but rather international agreements,” Fares Bayoush, a Syrian armed opposition commander, told Al Jazeera.

In 2012, diplomats from the US, UK, Russia, China and France, among others, formulated the Geneva Communique under UN auspices, a plan for peace in Syria to include political transition. The document has since formed the basis for the corresponding resolutions passed by the UNSC, namely resolutions 2118, adopted in 2013, and 2254, adopted in 2015, both of which reiterate the need for political transition.

Resolution 2118, though focused mainly on the use of chemical weapons during the war, is particularly significant as it refers to Chapter VII of the UN charter, the foundational treaty of the UN, which all member states are bound to.

According to 2118, in the event of “non-compliance” with the resolution, the UNSC member states, which include five permanent members: China, France, Russia, the UK and the US, as well as 10 non-permanent members, can “impose measures” on the warring sides in accordance with Chapter VII.

READ MORE: Six years on – The price of saying ‘no’ to Assad

“There are mechanisms in UNSC resolution 2118 which cannot be activated unless the regime rejects this resolution [2118]. The regime always claims that it is looking for a political solution – it does not reject the resolutions,” Mohamed Sabra, chief negotiator for the Syrian opposition during the last round of Geneva talks, told Al Jazeera.

“Our participation in Geneva is to discuss real mechanisms, either to implement the resolutions, or to demand that the UN and the [UN]SC activate the mechanisms in the UN charter, which allow for forcing the regime to abide by its obligations under international law,” said Sabra.

If proven to be in breach of resolution 2118, the Assad government could face an official international arms embargo, targeted sanctions, or other coercive measures under Chapter VII. This could isolate the Assad government within the international community, and possibly compel it to consider meaningful negotiations with the opposition.

For such measures to be introduced, the UNSC would need to pass another resolution on Syria declaring that resolution 2118 had been breached and authorising the use of force, but a Russian veto would block that from happening, as it has in the past.

Loopholes

Moscow has vetoed resolutions condemning Syrian government actions in the UNSC seven times in the past five years, most recently during a vote on a draft resolution threatening sanctions against parties using chemical weapons in Syria.

Though both Assad’s forces and the Syrian armed opposition groups have been complicit in committing war crimes, as was revealed in a recent UN investigation, neither are being pressured to stop.

“The evidence of crimes against humanity and war crimes is overwhelming. The problem is that at the moment Syria is an accountability-free zone. All sides, but especially the government, continue to kill, bomb and even deploy chemical weapons against civilians with total impunity,” Simon Adams, executive director of the New York-based Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, told Al Jazeera.

“UNSC imposed sanctions would not only be legal, the fact that they haven’t been imposed already is a disgrace. Russia’s veto has created a cloak of impunity for Assad,” said Adams, whose organisation works closely with the UNSC.

“That’s why the failure of the UNSC to uphold its responsibility to protect is so devastating. Russia’s vetoes mean that more people will die, more cities will be destroyed, more refugees will flee, and the civil war will continue,” he continued.

But the Syrian government claims it must battle “terrorism” before discussing any diplomatic solution. It has succeeded in adding “counter-terrorism” on the agenda for the planned talks later this month, which, some analysts describe as a distraction ploy to continue its military offensive against the armed opposition.

“The government’s claim that it is committed to international law and achieving a political solution is necessary for the silence of the international community,” Mohammad Alahmad, a professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Arab Studies in Washington DC, told Al Jazeera.

“The Assad regime seeks the re-legitimisation of its rule through ‘negotiations’, while conducting military action in parallel,” added Alahmad.

Besides the threat of Russian vetoes and the international community’s paralysis on the war in Syria, analysts say the absence of a consensus on what a political transition would look like is a major staller in the process.

“The regime’s obstruction is the same thing as rejecting transition, but the important point to keep in mind is the absence of consensus about what political transition is. I do not believe that Resolution 2118 can be triggered if the regime rejects the opposition’s view of transition,” Steven Heydemann, chair of Middle East studies at Smith College in the US state of Massachusetts, told Al Jazeera.

The issue of political transition in UN resolutions and the Geneva Communique is “left purposefully vague”, Noha Aboueldahab, a Visiting Fellow at the Brookings Doha Center, told Al Jazeera.

The Geneva Communique, stipulates that a transitional governing body “could include members of the present government and the opposition and other groups and shall be formed on the basis of mutual consent”. The fact that the document “does not make any specific mention as to who exactly in the current government should stay on” means that the “question of Assad’s hold onto power remains a key sticking point,” said Aboueldahab.

Alternative scenarios

Moving forward, the opposition “can demonstrate that it has international law on its side – that its position is legally correct and that Assad may be violating international law,” said Milena Sterio, professor of international law at the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law in the US state of Ohio.

“At some point, leaders become too ‘rogue’ and too isolated that it hurts them in the international community. The hope is to corner Assad, to isolate him politically and to get him to realise that if he wants any hope of participation in international relations and in the international community on behalf of Syria, he must negotiate with the opposition in good faith,” Sterio told Al Jazeera.

|

|

But despite the presence of a ceasefire in place since December 30, Syrian government advances on opposition-held territory have not halted, leaving the opposition to believe that Assad favours a military solution to the war.

With wavering Turkish and US support for the armed opposition, some predict there will be a “Somalisation” of Syria, as UN and Arab League envoy Lakhdar Brahimi predicted several years ago.

“Saudi and Gulf support will ensure that an insurgency continues. This means that pockets of Syria will remain in the hands of the opposition while others will remain in the hands of the Syrian government,” James Gelvin, a professor of the Middle East at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) said.

“As in Somalia, there will be a government that has a permanent representative to the UN, that will issue passports, and that will print postage stamps. But, as in Somalia, that government will not have full control over the territory within its borders,” Gelvin told Al Jazeera.