How Fukushima gave rise to a new anti-racism movement

The Fukushima disaster of 2011 ignited an anti-racism resistance movement in Japan to defend minorities such as Koreans.

Tokyo, Japan – In the low light of a pop-up restaurant in Ebisu, I sit across from Sabako as she takes pictures of the two onigiri (rice balls) that have just arrived at our table.

Sabako, who spoke to me under a pseudonym, is friends with the chef, a fellow activist who caters at anti-racism, LGBT, and music events in Tokyo. She takes a few minutes to upload the photos to Twitter using #OnigiriAction. Activists had been using this hashtag for several days in late November 2016 to raise awareness of poverty and food insecurity throughout Japan.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat happens when activists are branded ‘terrorists’ in the Philippines?

Are settler politics running unchecked in Israel?

Post-1948 order ‘at risk of decimation’ amid war in Gaza, Ukraine: Amnesty

Sabako is one of the many activists who took to the streets and social media in the aftermath of Japan’s mega-disaster of a 9.0 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear reactor meltdowns on March 11, 2011.

With 18,000 people dead or missing in the tsunami and thousands relocated, 3/11 – as it is commonly called by people in Japan – remains a deeply traumatic moment six years later.

In the ensuing panic over the spread of radiation throughout eastern Japan, Sabako, her teenaged child, and other family members fled Tokyo for the northern city of Sapporo. She stayed there for a month. Sabako signed up for a Twitter account and upon her return to Tokyo began regularly attending anti-nuclear rallies and demonstrations. She was searching for answers about the risks of radiation for her family, but also, simply angry at what she saw as a lack of accountability by Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) and other entities responsible for the nuclear disaster.

These days, however, her time and focus have shifted to a battle against racism and anti-foreigner hate speech.

READ MORE: The debate over South Korea’s ‘comfort women’

After Fukushima

The rebirth of anti-discrimination social movements in Japan is one of the unexpected stories of 3/11.

Fukushima “awakened” first-time protesters in the tens of thousands to both the fragility and potentials of democracy in times of crisis. Yet this mass mobilisation did not merely represent activists’ attempts to build a new nation from the rubble of disaster. Rather, escalated feelings of distrust in government, media, and scientific authorities, in addition to a deep sense of remorse, shook up notions of what it means to be Japanese and to live in Japan.

Minority-led civil rights movements by ethnic Koreans, Buraku (a historically discriminated-against social caste), and indigenous groups, such as Ainu and Okinawans, have existed in Japan throughout the 20th century.

But what anti-racism activists have aspired to after 3/11 is different. Primarily an ethnically Japanese movement, they view racism as a problem that is harmful to all aspects of society. These activists seek to make the anti-racism movement mainstream among Japanese people and to take on the physical and emotional labour of activism as a means of alleviating the risks and burdens faced by minorities.

At its peak in 2012, the movement against nuclear energy drew crowds of 200,000, with activists occupying the streets and pavement in front of the prime minister’s residence and the National Diet, the Japanese parliament, in Tokyo.

|

|

Leading up to this in April 2011, one month after the disaster, culture critic and former vice editor-in-chief of Music Magazine Noma Yasumichi helped found TwitNoNukes, a Twitter-based group that quickly became a bridge for connecting protesters of diverse political affiliations and backgrounds around a common anti-nuclear cause. Many activists turned to Noma as an opinion leader among what they saw as a sea of tepid media coverage and conspiracy theories slandering minorities on Twitter and other social media.

Standing up for Koreans and other ethnic minorities

In February 2013, Noma put out an appeal on Twitter in response to what he saw as an imminent threat: the nationalist group, Citizens’ Association to Oppose Special Rights for Resident Koreans (Zaitokukai), was marching in Shin Okubo, the Koreatown of Tokyo. Outside Tokyo, they also targeted the ethnic Korean enclave of Tsuruhashi in Osaka, and Sakuramoto, a multicultural neighbourhood in Kawasaki.

Their primary target was Zainichi Koreans, one of Japan’s largest ethnic minorities, which includes a diverse demographic spanning generations, from Koreans forcibly migrated under Japanese prewar colonial conditions to “newcomers”, many of them commercial purveyors of K-pop and Korean food. Noma’s appeal was a call to action against the racists.

Founded in 2006, Zaitokukai had previously targeted a 14-year old Filipino girl in 2009 – after her parents were deported for overstaying their visa – by protesting outside her home and school. They gained further notoriety the following year, after surrounding an ethnic Korean elementary school in Kyoto, verbally abusing the students there by calling them “children of spies” and “stinking” of kimchi.

3/11 had opened a new door for xenophobic politics.

As anti-racism activists often see it, political chaos and social unease in the aftermath of the disaster allowed groups like Zaitokukai to amplify their brand of xenophobia and racial scapegoating. Ultra-right internet users fomented panic on websites like 2Channel, the Japanese website that inspired 4chan. Even in 2017, the website boasts over a million new posts every day.

They accused Zainichi Koreans of exploiting national welfare systems and spread rumours that Japan’s mass anti-nuclear protests were run not by “real Japanese” people, but by seditious foreigners. While capitalising on mounting geopolitical tensions in East Asia, this bellicose rhetoric evoked the social terror sparked by other disasters in Japan’s past, such as the aftermath of the 1923 Kanto earthquake wherein rumours of espionage and other criminal mischief led to the massacre of 6,000 Koreans living in the greater Tokyo area.

Along with several other core members of TwitNoNukes and a handful of artists and designers, Noma formed Shibaki-tai. This invite-only, all-male “crew” was inspired in part by punk and transnational Antifa movements of the past. To counter Zaitokukai’s demonstrations and harassment of shopkeepers in Shin Okubo, Shibaki-tai positioned themselves in the victimised neighbourhood to protect shopkeepers and residents.

![Noma Yasumichi (centre), founder of TwitNoNukes and the Counter-Racist Action Collective. Photograph from September 23, 2014, in Roppongi, Tokyo [Courtesy of Natsuki Kimura]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/8cde3322d08b486cb0ed068bacdb6abc_18.jpeg)

WATCH: Japan – Guilty Until Proven Innocent (26:01)

Fighting racism

“Anger is an energy,” Noma states, as we sit down one afternoon in a smoky coffee shop in Shinjuku.

This philosophy describes both the underlying emotions of protest but also the momentum born from physical action. Shibaki-tai’s tactics of rage and anger – their tendency for styles steeped in masculinity and defiance of respectability politics – drew a backlash from conservatives and progressives alike. Despite the controversy, the group helped raise the profile of a new wave of anti-racism counter action, bolstering existing organisations like Otaku of Antifa (OoA), a group focused on fighting racism through the media of manga and anime, and inspiring the formation of new direct action groups such as the Menfolk.

Sabako describes her first counter-protest as a “dumbfounding” experience. Despite growing up in a progressive household and being relatively sensitive to issues of discrimination, witnessing hate speech in person was a shock to her. Zaitokukai’s signs were worse than they are now, Sabako explains.

She describes Zaitokukai’s now infamous slogans: “Beat the Koreans!” “Die!,” “Kill!” and calling Koreans “cockroaches” and “maggots”.

“I got angry from the bottom of my heart,” she says. “Many of us, especially the women, talk about feeling shock and fear, but for me – it wasn’t like that; I was just pissed off, I wanted to destroy [the hate speech movement]. We absolutely have to stop this – is what I thought – I remember this [feeling] clearly.”

Shibaki-tai eventually morphed into the Counter-Racist Action Collective (CRAC). They set up local satellites to counter-protest hate speech demonstrators across the country – in Osaka, Kyoto, Hokkaido, Okinawa, and even Fukushima Prefecture. CRAC built on its roots as culture workers, musicians, and designers in their fight against racism. They designed T-shirts and hats to make Antifa fashion “cool” and threw club parties.

According to Japan’s Ministry of Justice, Zaitokukai and other similar groups staged over 1,100 hate-related rallies and demonstrations between April 2012 and September 2015.

Although focusing on Zainichi Koreans, Zaitokukai’s demonstrations have included a broad range of victims, including Chinese, refugees, and migrant families. Fixated on the notion of unearned privileges, the organisation even targeted victims from Fukushima who had received government assistance.

Hate speech ban

Eventually the hate speech demonstrations and Zaitokukai members began dwindling in numbers, particularly following scandals such as the arrest of their leader Makoto Sakurai in the summer of 2013 and a Supreme Court order ruling that the organisation pay 12 million yen in damages (approximately $100,000) for a 2009 incident in which they harassed elementary school students at a Korean school.

A combination of increased media attention and collaboration between activists, policymakers and human rights organisations led to the United Nations issuing a stern recommendation for Japan to rectify the problem of hate speech in the summer of 2014.

This culmination of activists’ efforts, in collaboration with policymakers and human rights workers, came in May 2016, when Japan passed its first national ban against hate speech.

Yet in 2017, hate speech demonstrations against Zainichi Koreans and other foreigners continue in public spaces.

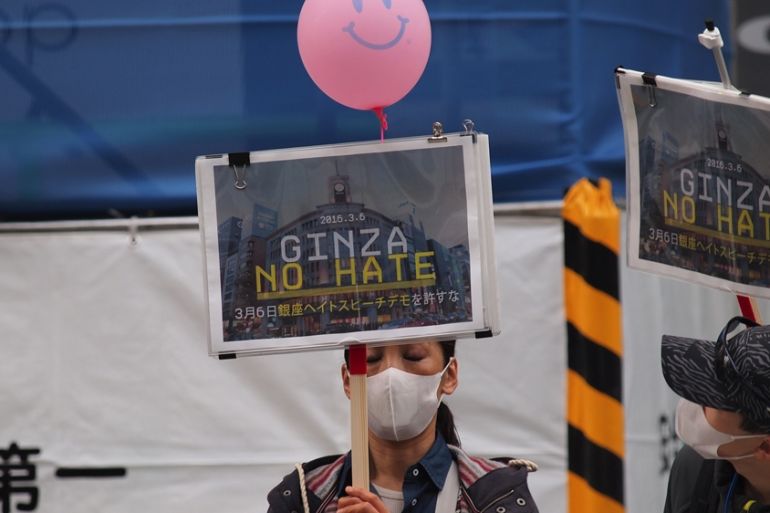

Activists and other critics blame this phenomenon on the law’s weaknesses – they claim it currently lacks the teeth to deliver penalties for offenders. Shrunk down to usually less than a hundred marchers on the Zaitokukai side, the demonstrations have moved from Korean neighbourhoods like Shin Okubo to prime tourist neighbourhoods, such as Ginza and Akihabara. A February 20, 2017 demonstration in Asakusa, home to major attractions, the Tokyo Skytree and the Senso-ji Temple, commenced directly opposite a queue of buses servicing large numbers of Chinese tourism groups. While numbers on the counter-protest side have similarly decreased, they appear to outnumber hate speech demonstrators significantly.

Hate speech in the form of vitriolic racist abuse on social media remains prolific. Some Zainichi Korean women who have become visible in the anti-racism movement even report being the targets of stalking at their workplaces and in their neighbourhoods. This has spurred activists and sympathetic politicians to advocate for legislation specifically addressing the problem of online hate speech.

Activists worry that the deep roots of discrimination in Japan go beyond hate speech. In Tokyo’s 2016 gubernatorial election in July, former Zaitokukai leader Makoto Sakurai garnered around 110,000 votes. Though only a fifth place ranking, and slightly less than two percent of the popular vote, Sakurai went on to found the far-right Japan First Party the following month.

|

| “We are already living together”, a popular slogan of the anti-racism movement in Japan [Courtesy of Natsuki Kimura] |

‘Living together’

In the autumn of 2016, I visit Shinjuku’s gay district to meet artist, Akira the Hustler, before his weekly bartending shift. The bar is the size of a narrow one-room apartment with a single counter stretching across its entirety. Vintage tea cups are neatly arranged on its shelves. A politics-friendly space, it is popular among Tokyo’s queer anti-racism and Antifa activists.

Akira is a seasoned activist and responsible for popularising the concept of “living together” within Tokyo’s anti-racism scene. The phrase derives from Japan’s HIV advocacy movement in the 1990s. It appears in random places throughout the movement: on a volunteer’s hat as we embark on a day of canvassing for an election, in the press release for a photographer’s gallery opening, in a photo of drag queens atop a float at the 2014 Tokyo No Hate Parade.

More than a slogan, though, it is a vision of shared vulnerability that includes foreigners, sexual minorities, people suffering from life-threatening and chronic illnesses, and those forced to live near or exposed to nuclear power plants.

“After all, I think people in some respect think [all of this] is unrelated to them,” Akira says, talking about the threads that bind “ordinary” Japanese people to conditions of marginality and social suffering in the country. “We think, ‘I don’t have a connection to that.’ That’s not what ‘living together’ should look like.”

The disaster, the ongoing and unresolved problems of rebuilding in tsunami-affected areas, and nuclear energy more broadly, all sustain a shared sense of uncertainty about the future for many in Japan.

Anti-racism in Japan has not been without its growing pains. The events of 3/11 triggered an awakened consciousness for many Japanese people, yet Zainichi Koreans and other marginalised groups have long understood the lived realities of racism and systemic discrimination.

OPINION: Black Lives Matter and Palestine – A historic alliance

Local, global

Increasingly, the anti-racism movement has striven to be more local, to collaborate and better support existing community-based organisations. Organisations like the Kawasaki Citizens’ Network against Hate Speech have drawn from its Zainichi Korean leadership to press the urgency of local city-level anti-hate legislation. They have also begun addressing the broader systematic nature of discrimination, teaming up with LGBT activists and migrants’ advocates.

As incidents of hate speech become fewer, activists have searched for other venues for civic participation.

Other groups under attack have also recently attracted greater attention from anti-racism activists. The ongoing Syrian refugee crisis – and a set of xenophobic cartoons negatively characterising refugee children as callously opportunistic – has elevated the topic within activist circles. Activists have also turned their attention to hate speech incidents in Okinawa. A number of them have travelled to Henoko and Takae to take part in Okinawans’ broader struggle around American military base constructions.

Japanese activists’ battle against racism often feels global. T-shirt designs in English, signs that feature photos of Trayvon Martin and Angela Davis, and CRAC Twitter accounts in the United Kingdom and North America gesture towards an international audience.

Twitter-savvy activists reference Black Lives Matter, NoDAPL, and the Women’s March as allies and examples. Political shifts towards nativism and authoritarianism in the United States and Europe have inspired some activists to see their battle as part of a larger one for democracy.

Katsuo Hada is one of the few anti-racism activists who remains an active member of the anti-nuclear movement, attending weekly rallies in front of the National Diet to this day. He still reflects on his past with regret. Prior to the disaster, he had long held reservations about nuclear power, but, in his words, “did nothing about it”. He harbours similar feelings about discrimination. For 10 years, he points out, xenophobia and racism had been brewing in the pits of the internet. It took the shock of public hate speech demonstrations to jolt him – and other Japanese people – into action.

Since 3/11, he has “felt a deep sense of remorse. A sense of responsibility. That it’s wrong to be silent.”

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy