Meet the Kenyans too poor to afford cancer treatment

The stories of two cancer patients reveal the desperate plight faced by those who cannot afford private care.

Garissa, Kenya – “Go and speak to that lady. Her son has just been admitted for the tenth time,” says Kadhra Mohamed as she fills out a medical report for the latest patient to be admitted to Ward One of the Garissa General Hospital, the largest in north-eastern Kenya.

It is early afternoon and so hot that patients are choosing to lie on the floor instead of on their hospital beds.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWoman, seeking loan, wheels corpse into Brazilian bank

UK set to ban tobacco sales for a ‘smoke-free’ generation. Will it work?

Poland lawmakers take steps towards liberalising abortion laws

Kadhra directs us to Harun Abdullahi, a 17-year-old leukaemia patient.

Harun was semi-conscious when he was brought to this poorly equipped hospital.

He asks his mother to remove his shirt because the heat is unbearable. Beneath it, his skinny frame is covered in sweat. An hour or so earlier, he had a blood transfusion – something that has become almost routine each time he is brought in.

“It has been almost two years of suffering now,” says Harun’s mother, Fatuma Adan. “This is new to me and I don’t know what to do.”

|

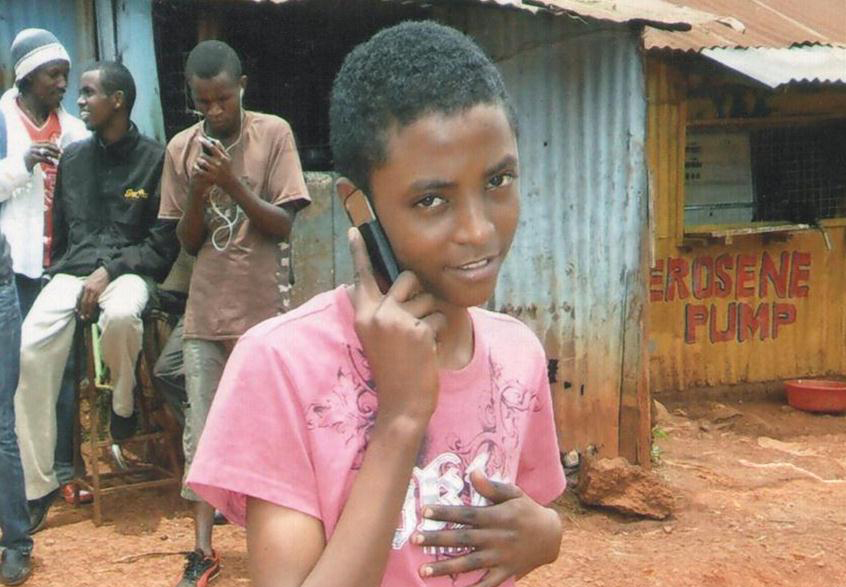

| A photograph of Harun Abdullahi, who died of cancer at the age of 17 [Osman Mohamed Osman/Al Jazeera] |

The 45-year-old single mother of nine has used all of her savings to take Harun to private hospitals in the Kenyan capital, Nairobi. She has even taken out loans, but still owes hospitals for his treatment.

“We kept on referring him to Kenyatta National Hospital [the largest referral hospital in Kenya, known as KNH],” says Kadhra. “But the family’s financial constraints have prevented them from [taking him there].”

“Unfortunately, money is the green light to better healthcare. If you have it, then you’re in a good position. For him, it’s sad,” she adds.

The cost of cancer treatment

In Kenya, cancer treatment is becoming increasingly expensive. Few private hospitals are equipped to provide treatment, which makes it possible for those that are to charge higher rates.

According to Faraja Cancer Support, an NGO that works with cancer patients, “the average [cost of] treatment ranges from $1,600 to $5,000, which is way beyond the reach of many Kenyans”.

Even the $5 cost of one radiotherapy session at the public hospital can be prohibitively expensive for poor Kenyans who live on a dollar or less a day.

And the number of people affected by this is on the rise.

According to the Ministry of Health, there are 40,000 new cases of cancer reported annually in the country. Another 27,000 patients succumb to the disease each year. From 2011 to 2014, cancer deaths rose by 23 percent, up from 17 percent in 2010.

![Kenyatta National Hospital is the largest public referral hospital in East Africa but is poorly equipped to treat cancer patients [Osman Mohamed Osman/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/7fcee61e31d94b4697679e657deda5c7_18.jpeg)

Machines such as the positron emission tomography-magnetic resonanceimaging scanner can be critical to detecting cancer. But such technology is unavailable in Kenya because it uses radiation, and the country does not have laws and mechanisms in place to enable the safe handling of radioactive isotopes.

In March 2015, hundreds of cancer patients were unable to proceed with their scheduled cancer treatment when the two radiotherapy machines at KNH broke down.

KNH is the largest referral hospital not only in Kenya but in East and Central Africa. It is also the only public cancer treatment facility in the country. But it is poorly equipped and overstretched.

Cancer victims from all over the country flood the facility to get cheap radiotherapy sessions. But they can sometimes wait almost a year for an appointment.

When the radiotherapy machines broke down again last September, Fatuma Hamisi, who had travelled to Nairobi from Kwale, about 500km away, was forced to reschedule her appointment for months later.

“I was called by the doctors for my radiotherapy session. After arriving, I was told that the machines had broken down,” the cervical cancer patient explains.

The machines in question have been in use for 20 years, treating up to 100 patients a day – instead of the recommended limit of 50.

Hamisi could not afford to find treatment elsewhere. Private hospitals can charge around $300, about 60 times more than KNH, for a single radiotherapy session.

Dr Catherine Nyongesa, a Kenyan cancer specialist, explains the importance of prompt treatment: “Cancer treatment for patients should start as soon as possible. If delayed, it matures from a curable stage to an incurable one, hence making it more painful and expensive to deal with. The main cause [of delays] is a lack of financial support.”

Cancer drugs are also expensive since they are not subsidised.

“Now I feel stranded,” says Hamisi. “I have no relatives here [In Nairobi]. I just report every morning [to the hospital] to check if they have fixed [the machine].”

|

| An artist’s impression of the new Tesla Cancer Centre that is being built in Nairobi [Image courtesy of the Tesla Cancer Centre] |

A more promising future?

Those Kenyans who can afford it often go outside the country for their cancer treatment. According to the country’s health ministry, each year 10,000 Kenyans are treated elsewhere – mainly in India and South Africa, which both have more advanced medical facilities. These patients are thought to spend a total of $108m on treatment abroad.

But all hope may not be lost. The government has set aside $206m for cancer care. Much of this will go towards diagnosis equipment and it should help to make treatment more accessible for cancer patients.

Kenya’s first ever comprehensive cancer diagnostic and treatment hospital is also being established. The Tesla Cancer Centre is a $10m project due to be completed next year.

The hospital’s management intends to import a positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET CT) scanner – an imaging tool that combines two scan techniques in one examination, allowing doctors to see any changes in the activity of cells and to know where those changes are taking place.

As well as attracting patients who would otherwise travel to India or South Africa for treatment, the facility will also start a foundation to help impoverished cancer patients.

As the World Cancer Day is marked, Kenyan cancer patients are left to hope that the treatment they need will reach them in time.

For Fatuma Adan, however, it is too late. Harun succumbed to the disease only hours after arriving at KNH, after he was referred there by the hospital in Garissa.

In her tiny rented house, she is left to mourn her only son and to wonder how she will repay the debts she accrued trying to save him.

“I do not know where to start from here,” she says, crying. “I have lost my son and I have debts to settle. Only God understands what I feel now.”

One thing she is sure of, is that her son would have received better treatment if she had been rich.

Follow Osman Mohamed Osman on Twitter – @OsmanMOsman