A bitter pill: How Syria broke my grandfather’s heart

Once a successful pharmacy owner, my grandfather’s days pass much more slowly now as he watches his country crumble.

In 1945, when nationwide protests against French colonisation gripped Syria, school and university students flocked onto the streets holding banners that declared “Syria is for the Syrians” in Arabic and French. Among them was a mild-mannered 17-year-old. But as the marchers weaved their way through the city, chanting and singing their slogans, he would slow down to let his classmates pass him by. Then, when they were out of sight, he would slip discreetly into the nearest alleyway. And there, leaning against a wall, he would study for his upcoming examinations.

My grandfather has told this story from his youth so many times that, over the years, it has become my own reference point to Syrian history. I see my country through his eyes and he has come to embody Syria for me.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsA year of survival in the Turkey-Syria earthquake zoneThis article will be opened in a new browser window

‘If I die, I die’: The allure of Pakistan’s death-trap route to Europe

Lojay, the preacher’s son minting romantic anthems from stripper therapy

The circumstances of its telling were often the same: After lunch on the veranda of my grandparents’ home in Homs; him in a grey robe, fruit picked from the land by my grandmother in one hand, a knife with which to cut it in the other; us, his grandchildren, gathered around, waiting for the tale to unfold between bites of a peach, apple or prune.

Perched on a plateau 400m above sea level, Homs sits as though by a window looking out across the Lebanese plains of Akkar and towards the Mediterranean Sea. Through that opening would blow a gentle sea breeze, spraying drops of water from my grandparents’ fountain upon us as we listened to him proudly declare that he wouldn’t have sacrificed an hour of study for the sake of the protests.

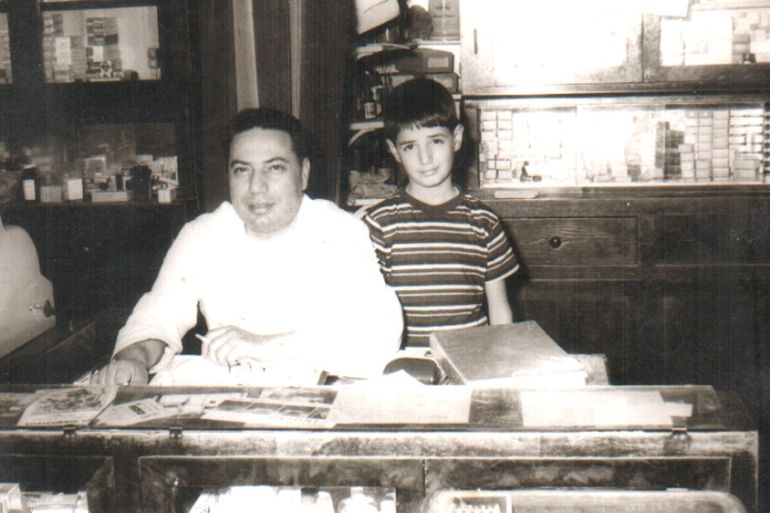

![Basma's grandfather and his son behind the counter of the Major Homs Pharmacy [Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/eb280a799d404b6e893ce26e0364241c_18.jpeg)

As the Ottoman Empire was dismantled in the wake of World War I, France took control of Syria. But the French presence wasn’t much welcomed and it spent much of the first half of the 1920s quelling rebellions.

It was against this backdrop that my grandfather was born in 1927, the youngest of eight siblings. His mother died when he was just four; his father when he was sitting his baccalaureate exams in 1945, the year of the independence uprising that led to France’s withdrawal soon after and the establishment of the Republic of Syria.

From his father, he inherited 70 gold coins. His two oldest brothers urged him to save the money and work as a tea boy in one of their stores. But my grandfather had other plans. He would become a pharmacist. So, he travelled to the capital, Damascus, and enrolled in what was then the University of Syria.

It was the only university in the country at that time, but changed its name to Damascus University when a second was founded, in Aleppo, in the late 1950s.

Unfazed by the attractions of the capital, he lived simply in order to save his inheritance to achieve his ultimate goal. He graduated with honours in the first class to be issued their diplomas by the country’s post-independence president, Shukri al-Quwatli. The degree took pride of place on the wall of the pharmacy he opened later that year.

Saydaliat Homs al-Koubra – or the Major Homs Pharmacy – was perfectly located on the curve of the main street in Homs’ bustling city centre. Its neighbours were vegetable vendors, book stores, clothes shops and the Old Clock roundabout.

Having spent all of his savings purchasing the shop, my grandfather had to borrow 2,000 liras from one of his sisters to stock its empty wooden shelves. In the early days, he would take the bottles from their boxes and display the two alongside each other to create the illusion of being better stocked.

And there he would work from seven in the morning until 11pm every weekday, sleeping in the shop on the weekends in order to serve customers during the night. Major Homs Pharmacy was the seventh to open in the city, but within just a year, its location and long opening hours made it the most popular.

With the money he made, my grandfather bought two gold coins every week – a saving scheme of sorts for those with little concept of how a bank functioned. He would keep them in the green metal safe that still sits in my grandparents’ room today.

Then, in 1957, at the age of 30, he bought a three-storey building in an upscale neighbourhood and, feeling emboldened, asked one of the most influential merchants in the city for the hand of his 20-year-old daughter in marriage.

Life had never been better for my grandfather. He bought shares in private enterprises, such as a sugar factory and the Homs Refinery. And, with four other pharmacists, he set up a pharmaceutical factory.

But his luck didn’t last long. In 1958, Syria formed a union with Egypt under the leadership of the populist Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser, who ordered that private companies be nationalised. My grandfather lost all of his investments overnight, while the pharmaceutical factory barely covered its costs.

“Big faith in God,” is a phrase he often repeats now when recalling those times.

Only the Major Homs Pharmacy remained a steady source of income – unaffected by the three coups and 10 changes of president the country endured during the shop’s first 15 years of existence. In fact, my mother recalls how it resembled a bakery, with customers carrying away their purchases as though they were loaves of bread.

Nabil, the oldest of my grandfather’s children, would spend much time there and remembers how representatives of the numerous different political parties vying for power and influence at the time would attempt to entice his father into their ranks. Every few days somebody from the Communist Party, Baath Party or Syrian National Party would hand out their fliers and ask my grandfather to join them – but they all went away in defeat, for my grandparents had little interest in political ideologies or rhetoric.

Which isn’t to say that they weren’t revolutionary in their own way: My grandmother, Radiyya Sbai, turned out to be just as much of a character as the man she married. One of the first women in Homs to drive a car, she would take it to the pharmacy on the weekends to deliver a fold-up bed to my grandfather as children ran along after the white German-made Opel, cheering at the sight. She laughs now at how an embarrassed Nabil would sometimes hide. But she didn’t challenge the conventions of the day out of principle so much as practicality – with five children and a husband who worked all of the time, she simply needed to be able to get around on her own.

When, on a winter’s day in 1970, my grandfather heard cheering outside, he went to see what was causing the commotion. Hafez al-Assad, the leader of the country’s latest coup and its new president, stood on the balcony of the Baath Party headquarters just a few metres away, making his first appearance in the city since the military takeover he dubbed “a corrective movement”.

As Assad’s voice reverberated all around, my grandfather returned to the pharmacy to attend to his customers. But he couldn’t help but be swept along at least a little on the wave of optimism that washed over the country. Syrians believed Assad’s rule would bring economic prosperity and stability, and while corruption and political repression marked the new president’s reign, the private sector flourished and the hardships of the previous socialist economy eased.

By the 1980s, as Assad restricted medicine imports in order to decrease the country’s trade deficit, the demand for local pharmaceuticals soared. My grandfather, and the pharmaceutical factory he was a partner in, was well-placed to benefit. The factory soon became the largest in Homs and then one of the biggest in the whole of Syria.

My grandfather grew wealthy. He bought a villa near the main highway to Damascus, a chalet in the coastal city of Tartus, and orchards in the village of Houla – now infamous as the site of a 2012 massacre. He also built a mosque in the neighbourhood where he grew up and named it after his father, Mustafa.

But in all this time, he never missed a day of work. And his newfound wealth left little mark on his attire. To my grandmother’s fury, he maintained his preference for short-sleeved checked shirts rather than the long-sleeved variety and the formal blazers she believed would better “reflect his age and status”.

Even his friends remained the same. He never sought to establish relationships with influential businessmen or officials and preferred the company of a group of simple, pious men, with whom he would often return from Friday prayers carrying grilled kebab and a large metal tray of kunafa, a Levantine cheese dessert soaked in sugar syrup.

![The Major Homs Pharmacy today [Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/dfb2307a109d4263a7baff341975215a_18.jpeg)

When, on a Saturday evening in 2000, it was announced that Hafez al-Assad had died, the bustling Old Clock roundabout, which bore a picture of the president with the caption “our leader forever”, came to a standstill.

Shops were closed, including the pharmacy, as everyone worried about what would come next. But the transition to Hafez’s son, Bashar al-Assad, proved smoother than people had feared.

The new president promised economic reforms intended to liberalise the economy and encourage foreign investment, but the development projects and privatisation of old state-run industries only benefited his inner circle and their business partners. Assad’s cousin, Rami Makhlouf, who controlled a network of lucrative monopolies, became the country’s richest man – and, to Syrians, a symbol of its corruption.

Iyad Ghazal, one of Assad’s friends, was appointed governor of Homs and became the city’s own Makhlouf. He envisioned an economic revival of the city he romantically labelled the “Dream of Homs” project. It entailed replacing parts of the city’s historic centre and its covered market with skyscrapers and modern shopping malls so that it might resemble a smaller scale Dubai.

By 2009, the land confiscation had begun – and shop owners knew their turn would come soon. It had survived for six tumultuous decades, but the Major Homs Pharmacy was under threat.

Frustration festered beneath the surface of Homs society. And then, in 2011, as uprisings broke out across the country, calling for freedom, democracy and an end to corruption, it could be contained no more. Two weeks into the protests, rallies erupted in the centre of Homs. At first, the protesters focused their anger on Makhlouf and Ghazal, but they soon began calling for Assad himself to go.

The security forces responded with a brutal crackdown that left hundreds dead within the first month of the uprising.

The frequency and sense of urgency with which my grandfather narrated his story about the 1945 uprising grew. He was eager that it fall upon the ears of his more rebellious grandchildren, lest they become so embroiled in the fervour gripping the country that they forget his supplication to focus on their education and self-development – just as he had all those years before. Of course, he understood their hopes and aspirations, and their anger too, but nothing was worth losing one’s life over, he stressed.

Like most business owners in the city centre, my grandfather tried to keep his pharmacy open. But as the violence escalated in early 2012, he was forced, for the first time since 1950, to close its shutters indefinitely.

The armed opposition had seized parts of the city, including where the pharmacy was located, and the government was using the full force of its arsenal to retake the lost territory. The buildings around the pharmacy were destroyed, the Old Clock roundabout was bombed, the street vendors’ wooden trolleys were burnt to ashes, and the pharmacy was completely looted, emptied even of its brown shelves and dotted tiles.

During the worst of the fighting in their hometown, my grandparents relocated to Damascus. There, my grandfather would roam the streets, entering every pharmacy he passed, examining its products and, gently, attempting to push the pharmacist aside so that he might take their spot behind the counter.

When they returned to Homs, his sons helped him set up a small pharmacy in a neighbourhood that had become a refuge for thousands of families who had lost their homes elsewhere in the city. But when clashes broke out there just months later, a shell fell right in the middle of the new enterprise. Thankfully, it was closed at the time.

Now my grandparents have returned to their villa – where my grandmother tends to her roses and apple trees, and my grandfather reads the Quran, watches his country crumble around him on television and wonders whether he will ever reopen the Major Homs Pharmacy. I suspect his days pass much more slowly now. And he has grown noticeably older over the past three years; his wrinkles deepening, his silver hair thinning. He is as sad and lost as Syria itself.