Unravelling the Afghan art of carpet weaving

Urbanisation and commercialisation threaten vestiges of ancient craft practised by tribes in Afghanistan.

It remains one of the last vestiges of an art predating civilisation itself – the ancient Afghan practice of carpet weaving.

Nomadic tribes in Afghanistan still weave carpets by hand for their own use, using patterns thousands of years old memorised and passed down from mother to daughter. They shear the sheep, collect the herbs used in dyes, and painstakingly weave and colour the carpets in a process that takes months.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

This would once have been a familiar sight in countries such as Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkey, but it has largely been replaced by factory woven carpets made for commercial purposes. Carpets make up 45 percent of Afghanistan’s exports – some $231m – but only a small fraction comes from handmade tribal carpets.

A tribal carpet is not just a rug, it is a legacy.

The rugs woven by nomads are placed on the floors and the walls of their tents, for warmth and decoration. Some may be specially made as wedding gifts for a bride’s dowry. But the role of carpets in daily life doesn’t end there. The hatchloo – the door flap of the tent – is a woven carpet. So are the carpets on which they eat and pray.

However, these rugs are never woven for sale. It is only when a rug woven for another purpose is replaced with a newer piece that the tribes take carpets to the market to trade. And it is only then that collectors such as Riyaz Bhat, who want to popularise the dying artform, can get their hands on them.

Bhat comes from a long line of carpet weavers in Kashmir, but travels to Afghanistan frequently to purchase carpets from nomadic tribes that have been producing handmade carpets for more than 500 years.

A typical haul for Bhat is 50 to 60 carpets, which takes him about four months to sell. Bhat goes twice a year to get rugs from the tribes, communicating months in advance to set up a meeting with each family. He buys sheep, rice, corn, fabric, and other materials in Afghanistan to trade for the carpets that traders have collected from their families.

“My basic purpose is not to sell a rug, it is to teach the world the value of a tribal rug,” Bhat told Al Jazeera from his shop in Doha, Qatar. “A tribal carpet is not just a rug, it is a legacy.”

Threat of commercialisation

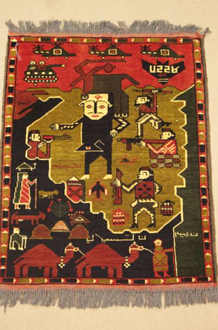

| Afghan war rugs | ||

|

During the Soviet war in Afghanistan, some tribal weavers began to weave the devastation and violence they saw into their carpets. The popularity of these soon spread, and it gained recognition as a form of Afghan folk art. In this war rug, Mujahideen combat a devil representing the USSR.

|

This attempt to promote the legacy of tribal rugs may be key to preserving their unique production.

Currently, nomadic weavers have to contend with competition from carpet factories around the world.

Omri Schwartz – manager of the Nazmiyal Collection, a New York-based company that deals in antique and decorative carpets – said historically this ends poorly for the weavers.

“It can take weavers a year and a half or more to create a fine piece,” Schwartz said by phone. “And sellers want to know they can get a supply of a certain size and type on a regular basis.”

He said investors prefer to create factories to produce carpets en masse and have weavers simply knot the carpets.

“Most weavers around the world today have no say in the design, they’re just labour,” Schwartz said.

Tribes in Afghanistan producing the carpets that Bhat buys may soon experience a similar phenomenon.

“Afghanistan has some of the fastest growing cities in the world,” said Francesca Recchia, an independent researcher specialising on urban transformation and creative practises in countries in conflict.

“It’s different than traditional urbanisation, which is somewhat evenly spread out. Rather it’s centred around a few main cities. It’s also influenced by the humanitarian emergencies the country has experienced,” Recchia told Al Jazeera by phone from the Afghan capital, Kabul.

Another factor that Recchia said may pull people towards cities is the lack of infrastructure in rural areas. “The difference in Afghanistan is that there are places that are completely cut off in the winter – if the infrastructure was in rural areas, people may not want to move into the city.”

Recchia said the global economy currently makes urbanisation an almost inevitable phenomenon, but not without cost.

“For the lower level of society, it’s not necessarily an upgrade, and cities have a very different system than many rural people may be used to.”

For carpet collectors, it could mean the end of carpets as an art form.

“Urbanisation kills tribal life,” Bhat said. “When people live in houses in a city they do not have enough space to keep 500 sheep or a proper loom, or access to the proper herbs to make natural dyes.”

Urbanisation and commercialisation have already put an end to unique, hand-woven carpets in much of the world.

“Every village had a distinctive way of constructing carpets in the 19th century,” said Schwartz. “You could tell where the carpet was from and they’d been producing it that way for 300, 400 years or more. Unique carpets being produced now are almost exclusively created on commission for the high end market.”

However, efforts of carpet collectors to promote the artistry of tribal rugs may yet pay dividends thanks to western consumers.

“For the first time in history, buyers [in the US and Europe] are beginning to appreciate carpets as a form of art,” said Schwartz. “I hope more people will take the time to appreciate them in the same way they would appreciate a masterful painting.”