Security improves in Mexico’s ‘murder city’

Juarez has seen a 42 per cent drop in killings and could offer lessons to other regions plagued by cartel violence.

Juarez, Mexico – Luis Alvarez slams his fist on the table of a posh hotel restaurant in Juarez when he overhears a discussion on drug violence in the city. “Why do they call us the most violent city in the world?” he shouts, as other guests look up from their huevos rancheros and fruit plates. “We are a centre of culture; we have more hotel rooms than El Paso.”

Alvarez was referring to the Texan city that sits just across the border from Juarez, but is light years away in terms of reputation. Known as Mexico’s murder capital, a 2009 study deemed Juarez “the world’s most violent city”. Security has improved since the peak of the violence, but entrepreneurs, government officials and tourist operators, including Alvarez, are having a tough time convincing the outside world to visit.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhy are nations racing to buy weapons?

Parallel economy: How Russia is defying the West’s boycott

US House approves aid package worth billions for Ukraine, Israel

“The city is quieter than it was a year and a half ago,” construction foreman Isiaj Isaias told Al Jazeera, as his builders refurbished a formerly abandoned downtown nightclub. In decades past, Juarez, a city of about 1.5 million people, was famous for its bars, restaurants and nightspots – before violence scared the tourists away.

Some of the major international news headlines about the city from 2010 include “Juarez – murder capital of the world”, “Americans killed in drive-by shooting at Consulate in Ciudad Juarez” and “decapitated head found on pillow in Juarez”. El Diario, the local newspaper of record, wrote an editorial calling cartels the “de facto authority” in the city after several journalists were murdered.

Since 2010, things have improved. Killings by criminal gangs in Juarez fell by 42 per cent – down to 952 deaths – in the first six months of this year, compared with the same period of 2011, which saw 1,642 killings, said Mexican General Emilio Zarate in July.

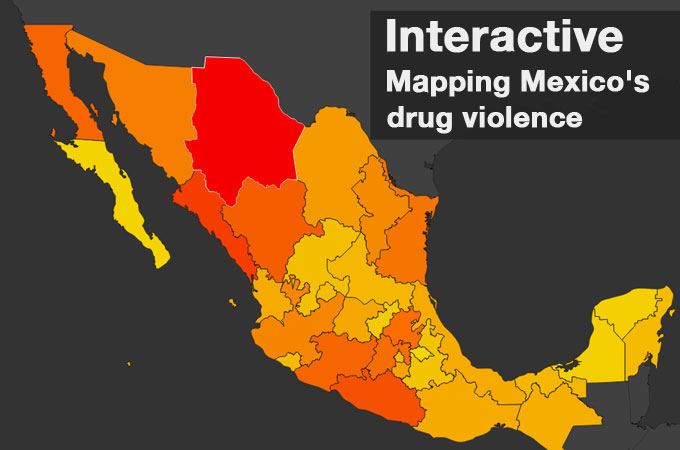

Across Mexico, more than 55,000 people have died in drug related violence since December 2006, and the border region has been at the epicentre of this carnage. “The major problem of this frontier is that our neighbourhood makes us a transit point for drugs,” Guillermo Terrazas Villanueva, spokesman for the Chihuahua state government, told Al Jazeera. “The US has a big hunger for drugs and we have a lot of problems because of that.”

Changing dynamics

Violence in Juarez is generally blamed on a turf war over smuggling routes between the Juarez cartel and the Sinaloa cartel, but a climate of general lawlessness, weak institutions, inequality and official corruption all contribute to a climate of impunity and insecurity.

In February 2011, the city was a war zone, with headless bodies appearing in parking lots, shoot-outs with automatic weapons in shopping malls (as customers continued to push their grocery carts) and plenty of “standard” murders.

Few dared to venture out at night. Police and military checkpoints criss-crossed the city and anyone who could afford to leave fled for the US or Mexico City. Burned out buildings stood as testiment to business owners who refused to pay protection money to gangsters. Other shops were simply boarded up, as residents were not going out and spending money.

By July 2012, the situation seemed better. Journalists could no longer easily access the police radios where sensitive internal communications were broadcast, and once empty bars and restaurants had filled up. Local people were more confident to go to the movies or out for a hamburger with their children.

“We asked for collaboration between all three levels of government and the citizens,” Juarez Mayor Hector Murguia told Al Jazeera, when asked how the city managed to lower the murder rate.

Other residents and analysts paint a more complicated picture of how the security situation improved, which focused on changing dynamics within the security services and the cartels themselves – rather than major improvements in public trust for local authorities.

Police problems

Violence sky-rocketed in 2008, as fighting between the Juarez cartel and the Sinaloa cartel intensified. Felipe Calderon, Mexico’s president (now preparing to leave office in the wake of July’s elections), deployed hundreds of soldiers into the city in an attempt to restore order. By 2009, the deployment had increased to some 7,000 troops and 3,000 federal police. These forces were part of the problem, rather than the solution, residents and policy makers said.

|

Juarez revamps crime tarnished image |

“The presence of federal police and the army was synonymous with kidnapping and drug trafficking,” Willivaldo Delgadillo, a human rights activist, told Al Jazeera.

One local journalist who spoke on the condition of anonymity likened the presence of outside security personnel, particularly the federal police, to an “occupying force”.

In March 2011, Juarez brought in Julian Leyzaola, Tijuana’s former police chief, to lead its municipal force. Known for his “take-no-prisoners” approach, Leyzaola has been praised by business owners and slammed by human rights groups for his tough-guy tactics.

A fierce critic of official corruption, federal police in Juarez reportedly opened fire on Leyzaola’s convoy in July 2011, underlining the underlying animosity between different branches of the security services.

“The federal police did not have good will from the community,” Villanueva, the government spokesman, told Al Jazeera. “They would finish work at 7pm and then go out robbing the citizens to make their real money.”

Citizen security

Made up of recruits from other states who were often posted in the city on short-term rotations, federal officers were notorious for crimes such as extortion against small businesses and kidnapping, Villanueva said, adding that federal police left the city in October 2011, after pressure from local officials.

Local police in Juarez have frequently been accused of corruption and ineptitude, but residents seemed happier with them than “outside” forces.

“Three thousand businesses in Juarez were facing extortion and restaurant owners were tired of paying this,” said Federico Ziga, head of the Camara Nacional de la Industria Restaurentera, a lobby group for the hospitality industry. “In the middle of 2011, municipal and state police began catching the extortionists,” he told Al Jazeera, noting that local criminals were not necessarily organised by the cartels – they were often simply unaffiliated opportunists trying to cash in on the criminal boom.

Rather than focusing on arresting major drug lords and seizing shipments – the drug war strategy preferred by the US – officials began focusing on citizen security.

“The Mexican government thought that, by capturing cartel leaders, the cartels would shrink and their operational capacity would be reduced,” Viridiana Rios, a scholar at Harvard’s Kennedy School studying drug violence, told Al Jazeera. This has not been the case, she said.

When it came to using force, Chief Leyzaola employed a strategy used in Bogota, Colombia, during the ultra-violent 1990s. “They divided the city into quadrants,” said Rios. “Once one quadrant was pacified they would move to the next one,” she told Al Jazeera. “That has helped.”

Cartel consolidation

Changes in police tactics aren’t the sole – or even necessarily the most significant – reason for security improvements, residents and analysts said. The turf war between the Juarez cartel and the larger Sinaloa organisation for control over smuggling routes seems to have tilted in favour of the Sinaloa group, according to most analysts, although some research groups including private intelligence-gathering corporation Stratfor, dispute this view.

|

Mexico’s ‘angels’ hit back at gang violence |

At the height of violence in Juarez in 2009-2010, both cartels employed smaller, less disciplined street gangs to do their dirty work, with the Juarez organisation outsourcing violence to La Linea and Barrio Azteca, while Sinaloa hired Artistas Asesinos and Mexicles, formerly a Texas prison gang. These smaller gangs were more prone to random acts of violence against the population and were more sloppy in their targeted assassinations of enemies.

Attacks from government security forces did not significantly stop the flow of drugs across the border, but they did fracture some of the cartels and change the dynamics of control over smuggling routes. “When the cartels fracture, they need new sources of income to battle each other,” Rios said. “They have to start doing their own operations in Mexico as they often don’t have the networks or power of corruption to move product into the US.” These operations, including kidnapping and extortion, are what bothered residents the most.

“Restaurant owners wouldn’t know if an extortionist worked for the cartels, or if he was a copycat criminal working alone,” Ziga from the restaurant association said. “Owners were tired of paying.”

The apparent dominance of the Sinaloa cartel, coupled with more effective local policing, has reduced these sorts of crimes. “This is not the Vatican,” said Villanueva, the state government spokesman, “but violence has dropped.”

Altered attitudes

Before the spike in bloodshed in 2008, drug dealing in Juarez was considered – on the whole – a US problem. Shipments could pass across the border and money would flow the other way, enriching poor young men, who often spread their money around. People here believed that, during “business disputes”, gangsters just killed each other, out of sight and out of mind.

Since the massacres at teenagers’ house parties, the constant killings and the blatant attacks on ordinary citizens, that mentality has changed among many Juarez residents.

Working as an exotic dancer at “The Joker”, a popular strip club, a 26-year-old woman calling herself Karina has witnessed this change in attitude first hand. “When traffickers used to come, the girls would want to talk to them, because they had money and we thought they were outlaws,” she told Al Jazeera. “Now, we are scared of them, we look at them with disgust and no-one wants to be around them.”

| In Depth |

Business has improved at the club recently, she said, as Juarez looks to reclaim its delightfully seedy image; the days when soldiers from Texas’ Fort Bliss, students and holiday makers could escape for a weekend of raucous fun could be returning.

Recent security gains should not be overstated. Large SUVs with tinted windows and no licence plates still speed across freeways in caravans of several vehicles, openly advertising their cartel connections and newspapers are still full of pictures of gruesome killings.

It is also possible that the killings have just moved away from Juarez itself, rather than decreased on the whole. Violence has increased significantly in other northern cities including Chihuahua City, the state capital, and Torreon in neighbouring Coahuila state.

With a new federal government, led by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), Mexico’s former political dynasty, set to take office in December, it remains to be seen if the gains in Juarez will be maintained or replicated in other parts of the country.

“The other day, someone asked if I believed in the legalisation of drugs in Mexico,” Mayor Murguia said. “That would only work if it was done all over the world together.” Otherwise, he said, Mexico would attract troublemakers and junkies from across the planet.

“Drugs hurt human beings,” the mayor said. “They must be treated as a health problem.” But for all of the talk of “security gains” in Juarez coming from Mexican officials, this sort of health-centred strategy shift doesn’t yet seem to be on the table.

Follow Chris Arsenault on Twitter: @AJEchris