On the campaign trail in Egypt

Leftist candidate Hamdeen Sabahi drew comparisons to Gamal Abdel Nasser as his cavalcade wove through Cairo streets.

On a recent night in the receiving room of a half-lit office owned by one of Egypt’s more successful movie directors, a television producer was telling stories about Hamdeen Sabahi.

The 57-year-old former left-wing student activist, jailed 17 times under two presidents, is now running to succeed the man who once threw him behind bars.

Campaigning under the slogan “one of us”, Sabahi has drawn comparisons to Gamal Abdel Nasser, and supporters often invoke his earthy populism – “we want someone who comes from Egypt” – to explain the draw of the square-jawed socialist from a rural town in the Nile Delta.

| Egyptian economy influences voters |

“Sometimes you found, if we have something very important and we are very busy, sometimes you lost him and found him talking with a cafeteria man,” recalled the producer, Sherif Fadel. “So I ask him why it’s very important. He said Ahmed – it’s the guy who’s preparing tea – Ahmed has a very big problem with his wife. I said, so what, we are very busy. He said, no, you have to understand, this is the biggest problem in his life, and you just have some business, so now it is very important to talk to him, and I don’t care if you are waiting for an hour.”

“He is very human,” Fadel concluded.

Sabahi’s appeal will be tested when Egyptians go to vote on Wednesday and Thursday, and opinion polls show him trailing a former foreign minister, a top Muslim Brotherhood official and a chimeric ex-Brotherhood doctor. But a day spent inside the Sabahi campaign – amid crowds who seemed equally stunned and happy to be able for the first time to shout questions to a man who needed their votes to lead them – seemed to show that no matter who wins, there is joy that it will at least be someone new.

Shoestring campaign

Sabahi’s headquarters sits in a quiet alley off of Lebanon Square in Cairo’s crowded Mohandiseen district, occupying two attached two-storey buildings: a set of converted apartments and the offices of well-known film director Khaled Youssef, who is Sabahi’s campaign coordinator.

On Sunday morning, the alley was buzzing with journalists, volunteers decked in green – Sabahi’s favourite colour – and an irate parking attendant who complained of the cars blocking the road and loudly suggested that nobody vote at all.

Sabahi’s campaign, his supporters often say, has run on a shoestring budget compared to those of frontrunners such as Amr Moussa, Mohammed Morsi and Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh. Sabahi’s events, it’s true, can look like block parties next to the expertly stage-managed, rock concert-style rallies mustered by Aboul Fotouh or the Brotherhood-backed Morsi.

Inside the headquarters, as a line-up of leftists, film producers and journalists prepared to endorse Sabahi at a press conference hours past its deadline, two staffers hurriedly taped a wrinkled Sabahi poster to a white board, where it hung askew as the cameras started to roll. Nasser’s image beamed from one side of a dangling campaign badge.

“We are a poor campaign, we don’t have money to give him,” said Hany el-Nabarawy, the head of the organising committee and an architectural engineer, standing in the back next to a one-phone room marked “Call Center”. “If we lose I think we will go again for the next time.”

Outside near Lebanon Square, Sabahi’s double-decker, open-top campaign bus idled as staffers made last-minute preparations. Men strolling by wearing business suits and galabeyas paused to take in the activity as journalists and volunteers ascended to the top. Then the bus pulled slowly away, blocking traffic to a cascade of horns as more supporters and a few enthusiastic bystanders made unsuccessful attempts to push themselves through the door.

Surge in support

Recently, Sabahi seems to have undergone a popularity surge, moving from an also-ran to a candidate very much part of the national discussion. Many Cairenes attribute his rise to a growing dissatisfaction with the other candidates.

|

“There’s a different attitude in people now. … Before, voting under Mubarak was a hassle: You go stand in a queue and you know a [regime] guy will win.” – Ahmed Hamad, mortgage lender |

Former Foreign Minister Amr Moussa and former Civil Aviation Minister Ahmed Shafiq (who briefly served as Mubarak’s last prime minister) are both tainted by their ties to the former regime. Mohammed Morsi is the Brotherhood’s candidate, and Aboul Fotouh left the Brotherhood only in 2011 and has courted the hardline Salafi vote. Such Islamist ties make both men unpalatable to liberals and secularists, not to mention an apparently growing number of observant middle- and working-class Egyptians who are dissatisfied and wary of the Brotherhood after it nearly won a majority in parliament.

Trailing the bus in a compact four-door festooned with Sabahi material, Ahmed Hamad – a 27-year-old mortgage lender originally from the Minya governorate – explained how the race had been developing 250km south of Cairo.

“When we talk to people in Minya who are voting for Abdel Moneim, they say ‘Sabahi is good but I don’t want to lose my vote,'” he said. “They say Aboul Fotouh is in the middle, not quite as bad as Morsi.”

Christians will lean towards Sabahi, Moussa, or Shafiq, and anyone who supports the revolution will vote for Sabahi, he said.

“There’s a different attitude in people now. In Minya I never imagined I’d be putting up these posters all day. Before, voting under Mubarak was a hassle: You go stand in a queue and you know a [regime] guy will win.”

As the car entered the busy thoroughfare of Arab League Street, a Morsi kiosk came into view in the median. Hamad reached out his window and slapped the Sabahi poster taped to his car. A Morsi supporter in sunglasses smiled and returned a thumbs-up.

“Amen, oh lord!” Hamad shouted.

‘The president is here!’

The car reached Gelaa Square, near the Nile, where the bus had stopped. Suddenly, as volunteers shook Sabahi posters at passing traffic, the candidate approached in a throng of supporters and journalists.

Sabahi boarded the bus, which began to move, and a few seconds later his silver hair popped out from the staircase leading to the top. Supporters swamped him with hugs and kisses. Mohammed Abdu, a 37-year-old man from Giza and the only on the bus wearing a galabeya, stepped in to shade Sabahi’s face with a campaign poster.

|

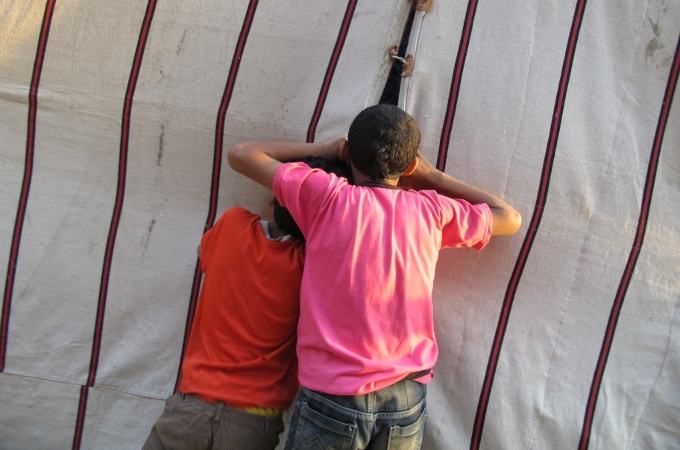

| Two young boys peek through the rally tent to watch Sabahi give his last speech [Evan Hill/Al Jazeera] |

The bus rolled through central Cairo, and Sabahi’s various theme songs blasted from roof-mounted speakers.

“Here! Here! Here! The president is here!” his supporters chanted.

Sabahi moved from the right side of the bus to the left and back again, waving to bystanders whose expressions seemed to reflect a surprised realisation that a presidential candidate was trying to win them over.

At the parliament building, a phalanx of around 100 black-clad riot police and military soldiers gawked as the bus rolled past. A riot cop pushed his hat back and stared. Others, somewhat incongruously, flashed victory signs and smiled.

One hundred metres farther down the road, traffic halted the bus near Mohamed Mahmoud Street, the site of a days-long November street battle between protesters and riot police that left more than 40 people dead and many more injured.

The bus quieted, and someone began to recite the Fatiha, the first chapter of the Quran:

“In the name of Allah, the most beneficent, the most merciful,

All praise is due to Allah, lord of the worlds…”

Sabahi joined in, the prayer finished, and the bus churned onward. After a stop near Cairo’s central rail station, a knot of journalists filed out, heading to another rally. A crew of construction workers called out to Sabahi from their scaffolding: “Take care of the poor!”

The tight streets of central Cairo widened into the slums of Manshiyet Nasr. Khaled Youssef, the campaign coordinator, leaned over the dashboard and stared out the front window, plotting a course that would take them through Sabahi supporters on their way to the final rally in the Matereya neighbourhood.

In the newly quiet, darkened seats behind Youssef, volunteers joked, and Sabahi descended to rest. He said little, occasionally leaning his head against the window and slumping in his seat to sleep. His day had begun much earlier and would not end until he was done with television interviews that night – the last before a two-day ban on campaigning.

Still, he addressed perhaps the thorniest issue of Egypt’s transition: how to ease the military out of power without provoking a confrontation.

“We would support the army in protecting the security, the borders and Egypt’s independence, without interfering in Egypt’s internal politics. All Egyptians will love the army,” he told Al Jazeera. “The military council mismanaged the politics. That will end.”

Two rows behind the dozing Sabahi, MP Basem Kamel, a member of the Social Democratic Party and one of the spokesmen for Tahrir Square’s youth during the 2011 protests, skimmed his Twitter feed.

“You can divide the candidates into three categories: Islamists, the old regime, and those who supported the revolution,” he said. “The only one who I believe is a good chance to win and my vote won’t be thrown away is Hamdeen Sabahi.”

Kamel serves on the parliament’s foreign affairs and housing committees, neither of which he said has been particularly effective at getting any results out of the country’s temporary government. Still, he was happily digesting the novelty of a presidential election in Egypt.

“I made a joke with Sabahi. Someone asked him for his mobile number, and I said, you have to give all the people your number,” he said. “All of this is new, and I think we are learning from this experience, and next time the result will be better.”

Populist notes

The bus looped into Matereya and halted near a mosque. In the street, rows of chairs were arranged under patterned awnings, and a crowd of several hundred watched and waited for Sabahi to descend. A cheer went up as he did, and they lifted him onto their shoulders and carried him to a stage at the front.

Sabahi spoke, hitting his populist notes. He promised not to follow the whims of the United States or Israel and that nobody would starve or be humiliated in Egypt.

“We will take the social justice from Islam and peace from Christianity,” he said. “We don’t want it secular or Islamic, we want it a national democratic country.”

Ahmed Awaad, a 45-year-old Nubian film director from Egypt’s south who has worked on the campaign, smoked a cigarette and watched from the rear.

“I know him personally and I trust him, and I have the same ideas as Nasserism,” he said. “He’s not going to return again to what Nasser did, no, he’s going to renew it.”

Outside the rally in the dusty lot where fruit and vegetables were stacked atop carts for sale, 19-year-old Ahmed Salah, a student, and 20-year-old Hussein Mostafa, who exports and imports elevator equipment, said they planned to vote for Sabahi and appreciated his support of the poor.

“He’s the best of a bad lot,” Mostafa said.

Mohammed Ahmed, a 26-year-old assistant at one of the market carts, approached and unfolded a piece of notebook paper. Between 8am and 2pm he had been recording the voting preferences of his customers, he said. His tally showed 29 check marks for Sabahi and roughly 10 for each of the others.

Around the corner, as dusk fell, 73-year-old pensioner Muhammed Abdel Rahman occupied his chair on the sidewalk, leaning on his cane and watching the traffic pass. He wore a gray galabeya, white skullcap and tightly trimmed beard.

“We as neighbours decided on Hamdeen,” he said.

With additional reporting by Nagham Osman.

Follow Evan Hill on Twitter: @evanchill