Difficult days ahead for Egypt

Analysts say the recent elections have closed the already small window for political participation.

|

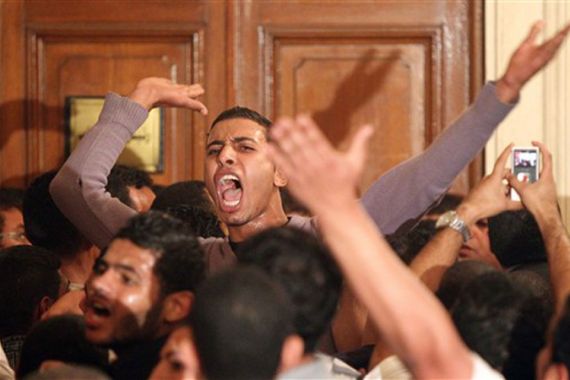

| Opposition supporters have been angered by the vote, but analysts say most Egyptians have not been mobilised [AFP] |

Egypt’s parliament has rarely been a platform for policy-making or serious political dialogue – more often acting as simply a rubber stamp for government policies. But, over the last decade and until the recent parliamentary elections, the presence of the Muslim Brotherhood and other vocal opposition and independent representatives inside parliament at least offered an opportunity to monitor the legislative process and raise issues such as the need for political reform and to tackle corruption.

Now, even that small window of political participation seems closed.

After the first round of parliamentary elections many of Egypt’s most influential political analysts and intellectuals have little optimism about the country’s political future. They feel that the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP) has gone too far in its bid to monopolise political power by crushing the Muslim Brotherhood and other, much smaller, opposition groups and say the election was marred by complaints of corruption, violence and vote-rigging.

No room for dissent

Abdullah al-Ashaal, a professor of international law and a former diplomat, said three points emerged from the elections: “First: the regime made a political decision to eradicate the Muslim Brotherhood and the opposition. Second: violence was used in a cruel way. Going to the polls was like putting one’s self into harm’s way. Third, the leaders of the NDP were too arrogant. Their actions and rhetoric were outside of the realm of any law or logic. We had hope in dialogue, but we discovered that we were naïve.”

Like many other Egyptian observers, al-Ashaal predicted a NDP crackdown on banned Muslim Brotherhood candidates to prevent a repeat of the 2005 elections, when they won about one-fifth of parliamentary seats. However, he thought the government would leave some seats for them and reward the smaller secular opposition parties who took part in the elections with enough seats to boost secular opposition to the Brotherhood.

Amr Hashem Rabie, the head of the Egyptian studies department at Al-Ahram’s center for political and strategic studies, one of Egypt’s most influential think-tanks, said: “All expectations were that the NDP had struck a deal with [the secular] parties, such as Al-Wafd and Al-Tajamou and [would] offer them some gifts [seats]. The talk was that the 88 seats occupied by the Brotherhood in 2005 would be distributed [by the NDP] among the other opposition parties.”

Al-Ashaal and Rabei were surprised that the NDP won 94 per cent of the 221 seats decided in the first round of voting – overshadowed, as it was, by complaints from the opposition and human rights organisations.

Based on the results of the first round, the opposition – both secular and religious – could win no more than 50 seats – less than 10 per cent of parliament – in the two rounds of voting. As a result, the Muslim Brotherhood and Al-Wafd party, the NDP’s two main rivals, withdrew from the elections citing widespread use of coercive and vote-rigging tactics.

“The results have created rifts inside all the political parties and groups that participated in the elections,” says George Ishaq, a former spokesperson for the Kefaya movement and a senior member of the National Association for Change, a group affiliated with Mohammed ElBaradei, the former UN nuclear chief, who has boycotted the elections.

Paving the road for succession

Al-Ashaal believes the government’s actions can be seen as part of a larger regional plan, supported by the US and Israel, to “politically eradicate” the Muslim Brotherhood and crack down on Islamist groups across the Middle East.

“There is a presidential election coming and there is political succession being prepared for. The regime does not need cosmetics at this moment,” he noted.

But, according to Rabie: “Trying to politically eliminate the Brotherhood is stupid … the government used military courts against the Brotherhood and they could not eliminate them. They included the Brotherhood in previous parliamentary elections but still could not eradicate them politically.”

He argues that the regime wanted to achieve “full political monopoly” before the upcoming presidential election, which may see a change of president for the first time in three decades.

Alienated masses

Many analysts believe that the Egyptian regime has been able to crush the opposition in such a manner because it has already succeeded in politically marginalising the Egyptian people over decades of political stagnation and undemocratic rule.

“People are satisfied with the status quo. They accept the ruling party. They are used to political stagnation,” says Milad Hanna, a prominent leftist thinker.

“The Egyptian people are not worried about the elections. They don’t follow the elections. They don’t vote.

“The elections are going on without any serious competition. I don’t see any street protests against the NDP. The ruling party has no serious competition and the Muslim Brotherhood cannot win enough votes to scare the NDP. People are not angry and are not revolting.”

Tariq al-Beshri, a widely-respected author and retired judge, fears that the Egyptian government has succeeded in weakening all organised political groups inside the country. He says that any sign of political reform was “limited to the media and intellectual elites”.

“For change to take place in any society there should be enough political street mobilisation. We don’t need more talking. We need to be able to act politically.”

But al-Beshri suspects that the Egyptian regime has weakened the various political institutions that could help to mobilise the people. “The labour unions were weakened. The parties were destroyed. The professional unions were disintegrated.”

And Rabie argues that the Egyptian civil society organisations that have mushroomed over the last few years are “empty from the inside”.

“You see parties and civil society organisations, but with no serious content. You have parties, but they are constrained by the law. You see a parliament, but it has no real authority.”

Moving the Egyptian street

Al-Ashaal does not believe that new political movements or new popular leaders such as ElBaradei can achieve much. “The regime will not accept any whisper of opposition, Egypt will suffer a lot,” he says.

But al-Beshri is more hopeful. “There are no people without [an] opportunity [for change]. I am sure there are opportunities in the future. But, I cannot predict them at this moment.”

He even suspects that an opportunity for change may come from within the ruling party itself, which is reportedly suffering from serious internal divisions. “The ruling party has run in some districts with several candidates competing over the same seat …. It has internal contradictions.”

Ishaq is more optimistic and thinks the government crackdown could lead to “a dialogue among the opposition to form a united bloc”. He says his National Association for Change has been working hard to reach out to the people and mobilise them. “The Egyptian people have been boycotting politics for 50 years. We should not hope to change Egypt in 10 years.”

Still, many observers believe that the Egyptian opposition is weak and divided. And they see the new political groups, such as Kefaya and the National Association for Change, as intellectual and upper class, active only in the cities and unable to reach out to the lower classes or to mobilise the Egyptian street.

What is certain, according to Ishaq, is that: “If the Egyptian street does not move there will not be any change. The coming days will be very difficult ones for Egypt.”