Aids: Is the tide turning?

Experts claim that an increasing number of countries have managed to stabilise and decrease infections.

|

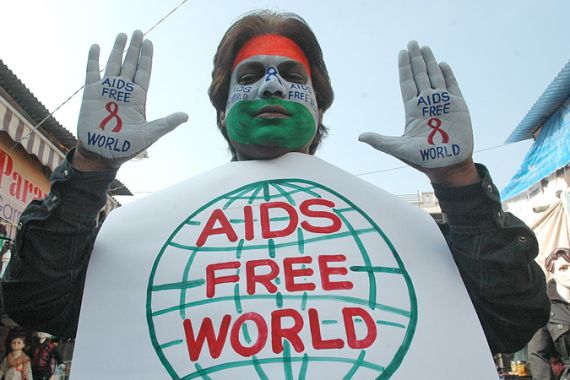

| Though the tide may be turning in the battle against HIV, will poor governance, profit maximisation and economic disparity prevent a halt in the spread of the virus? [EPA] |

According to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/Aids (UNAIDS) there are currently 33 million people said to be HIV positive, over the past 12 months there were 2.6 million new cases. Last year 1.8 million HIV positive persons died of Aids-related-illnesses. The figures provide grim reading.

Historically, being HIV positive meant an inevitable early passing as a result of Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (Aids). However, due to progress primarily in medical science, the tides are turning, with HIV positive persons experiencing an improvement in the quality of life as well as an increase in life expectancy.

More so, Aids experts claim that an increasing number of countries have managed to stabilise or achieve a decline in new Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infections, potentially leading to a halt in the spread of the virus.

According to the 2010 UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS epidemic, new HIV infections in 2009 were 20 per cent less than those recorded in 1999, while the number of Aids-related deaths worldwide were similarly 20 per cent fewer than in 2004 (the peak of the crisis).

“We are breaking the trajectory of the Aids epidemic with bold actions and smart choices,” Michel Sidibé, executive director of UNAIDS, proclaimed at the launch of the report. “Investment in the response [to Aids is] paying off, but gains are fragile – the challenge now is how we can all work to accelerate progress.”

The report, which surveyed 182 countries, noted that even though there had been an increase in the number of people living with HIV between 2008 and 2009, the increase was due to increased life span resulting from successful antiretroviral treatment (ART).

Crucially, the report found that the rate of new HIV infections had stabilised or decreased by 25 per cent in 56 countries. Four out of the five countries with the “largest epidemics” in sub-Saharan Africa, the region most hit by the pandemic, had also seen new infections reduce by 25 per cent.

‘Behavioural change’

Alan Whiteside, the executive director of the Health Economics and HIV/Aids Research Division (HEARD) at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, told Al Jazeera that the positive shift in statistics pointed to greater awareness of basic prevention methods, leading to a change in behaviour.

“There is clear evidence of behavioural change such as increased condom use and the delaying of sexual encounters,” Whiteside said.

However Whiteside clarified that it was important to note that while the “rate is decreasing; the total number of infections still continues to rise … it is just that the rate of new infections is slower.” Reacting to the report’s findings, Matthew Kavanagh, Director of US Advocacy at Health Gap, said that the “tide is turning”, but cautioned that there was still much to do.

“We are seeing the fruits of the investments made over the past twenty years, the rate of infections are decreasing and now it is a case of maintaining progress. There is a major disparity between those living with Aids in the North and those living in global South … this was meant to be the year of universal access, but just 36 per cent of those in urgent need of medication in poor countries have access to antiretroviral treatment.”

According to UNAIDS, the total number of HIV positive in need of antiretroviral treatment in low and middle income countries amounted to an estimated 15 million. Meaning that at the end of 2009 only 5.2 million people had access to the life-saving drugs. However the UN notes that this figure was close to 700,000 in 2004 and 30 per cent more than 2008.

“It is a chronic condition for those who have access … others who don’t have access, will simply die … this is a major disparity between the rich and poor countries,” Kavanagh added.

Prevention vs Treatment

Hot on the heels of the UNAIDS report, the US Institute of Medicine (IOM) released the Preparing for the future of HIV/AIDS paper, which flips the optimism of the UN document on its head to reveal a rather grim account of the Aids crisis in Africa, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, the so-called epi-centre of the pandemic.

The IOM report predicts that up to 70 million Africans will be HIV positive by 2050 unless governments act decisively in advancing preventative measures over treatment.

“In Uganda and a few other nations, [there aren’t] enough health care workers or ART to meet demands, and health centres are increasingly turning away patients who need these drugs to survive,” said David Serwadda of the IOM.

Alan Whiteside, from HEARD, corroborates that the real challenge hereon will be “sustaining prevention and scaling up treatment … even if it is expensive.”

Interestingly, the UNAIDS report shows a correlation between the increase in antiretroviral facilities and lower infection rates. Three successful case studies being Botswana, Nambia and Rwanda where access to facilities was increased to around 80 per cent for those in need of the treatment, in turn achieving a 25 per cent reduction in infection rates.

Sufficient Progress?

Whiteside believes that “we understand HIV, and in a large part, the fear, horror and terror has dissipated; we have huge amounts of knowledge about the virus.”

“In many ways, the virus has advanced the sciences, pushed research and progress in cell-biology, immunology, epidemiology, [and] even the social sciences.”

Earlier in 2010, Aids researchers reported that HIV-positive persons who regularly completed their drug cocktails were 92 per cent less likely to infect partners. While in July, a study indicated that a microbicide could help protect women against contracting the virus.

But Whiteside is measured about the holistic approach to the epidemic and the fallibility of the long term approach. The search for the elusive “cure” has always been half the story.

Addressing the social milieu in which HIV/Aids has spread, especially in the Southern Africa region has always been the other half of the plot. “I think we realise, more than ever before, that Aids is complex [and] in Southern Africa, one of the root causes of the crisis is linked to the political economy of the region, uneven [economic] development … and this cannot be ignored.”

Kavanagh agrees that despite the gains, “we have not adequately addressed the epidemic as a societal issue … it is not a medical issue, it is a societal issue, but HIV/Aids did bring social issues into focus.”

But did the stabilisation of HIV/Aids statistics come as a result of the hard work, or was it merely a case of the pandemic reaching equilibrium at some point?

“This is something we ask ourselves all the time,” Whiteside says. “We do believe the improvements are a result of the work and the conversation that we have started … but it is hard to attribute causality.”

You can follow Azad on twitter @azadessa