The peace prize in the digital age

The internet has been lauded by Nobel Peace prize-winning Chinese activist Liu Xiaobo as “God’s gift to China”.

|

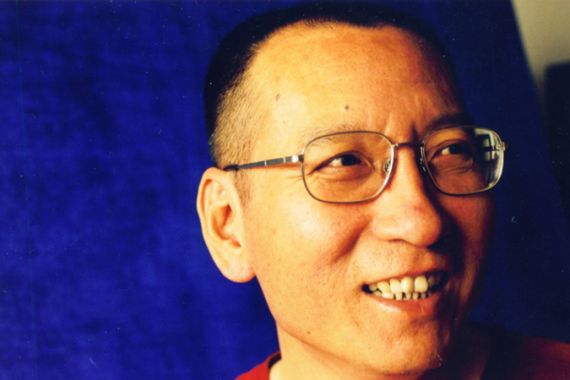

| Liu Xiaobo continues to be a thorn in the side of Chinese political repression irrespective of incarceration [EPA] |

In April 2009, Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo published an op-ed praising the internet for bringing about ‘the awakening of ideas among the Chinese’.

Just two months later Liu, who had previously been imprisoned for participation in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, was charged with inciting subversion of state power and sentenced to eleven years in prison plus two years deprivation of political rights.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsCould shipping containers be the answer to Ghana’s housing crisis?

Are Chinese electric vehicles taking over the world?

First pig kidney in a human: Is this the future of transplants?

On October 8, it was announced that Liu was the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. He became China’s first Nobel laureate, after more than a century of exclusion. He was supported by past winners Vaclav Havel, the Dalai Lama, and the Archbishop Desmond Tutu, while his own government has warned the Nobel Institute against giving Liu the award, threatening strained relations between Oslo and Beijing.

Liu also became, in a sense, the first “digital” peace laureate. Though his history as an activist pre-dates the internet, his praise for it is well-documented; he once dubbed the internet “God’s gift to China”, in recognition of its role as a tool for dissidents.

Its utility to his activism is also well-documented; Charter 08, Liu’s impassioned plea for democratic reform in China, can attribute its widespread circulation to the internet, and a number of China’s top bloggers are signatories.

Ironically, one of Liu’s fellow nominees is the internet itself, nominated by Italian journalist Riccardo Luna, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Shirin Ebadi, and 160 Italian parliamentarians. The nomination is backed by a group called Internet for Peace, led not only by Luna and Ebadi but also such “netterati” as Creative Commons CEO Joi Ito and inventor of One Laptop per Child Nicholas Negroponte.

Though the internet most certainly makes for a unique candidate, the claim that it “shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations” and thus fulfil the legacy of Alfred Nobel, is a dubious one. As Evgeny Morozov argues, awarding the internet the Nobel peace prize would be to downplay its many sinister uses. He asks: “Would we ever give the Nobel award to the machine gun just because it could be used by UN peacekeepers?”

Indeed, the internet alone is not worthy of the award. The internet is home not just to thousands of activists working for a better world but also to pornography, terrorism, an online university run by Glenn Beck. The internet alone is not a peacemaker. Rather, it is simply a single tool in a long line of others: the printing press, the telephone, the fax machine.

Which is not to say that Liu is wrong about the role of the internet in Chinese activism. In a repressive society where the government controls the press and the television, the internet often remains the freest space for speech, even with pervasive filtering in place. More importantly, as Liu notes, the internet levels the playing ground, allows anyone to become a star in their field.

Awarding Liu Xiaobo means honouring the struggle of Chinese democracy and human rights advocates, but it also means honoring a new generation of activist, for whom the internet is not a life saver but simply a tool that makes navigating the world just a little bit easier.

Jillian York is a writer, blogger, and activist based in Boston. She works at Harvard Law School’s Berkman Centre for Internet & Society and is involved with Global Voices Online.