Forgotten, Canadians remain in Iran’s prisons

With embassy closures and tough talk, Canada distances itself from Iran – but what of its citizens still jailed in Iran?

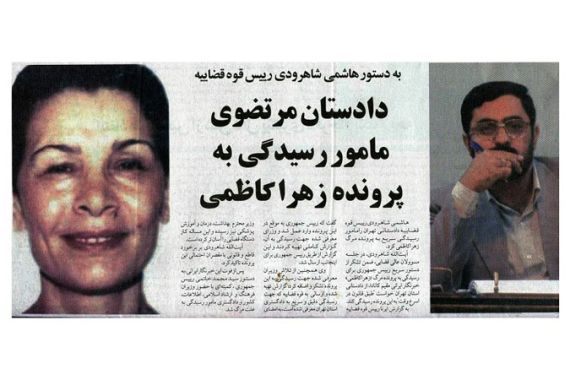

By the time Iranian authorities ordered Ziba Kazemi’s life support machines turned off in July of 2003, the Iranian-Canadian had been in their custody less than three weeks.

She was never charged with a crime.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat happens when activists are branded ‘terrorists’ in the Philippines?

Are settler politics running unchecked in Israel?

Post-1948 order ‘at risk of decimation’ amid war in Gaza, Ukraine: Amnesty

She never set foot in a court of law.

She never spoke to a lawyer.

Kazemi, who was born “Zahra” but was never called that name, was arrested outside Evin Prison in June of 2003 when she was photographing a protest.

The government had instituted mass crackdowns against university students there, and Kazemi, who was actually on her way to Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan for other projects, decided to document what was happening.

To put Kazemi’s presence there in context, it’s important to note that she had been working as a Canadian-based photojournalist for a decade, working in Palestine, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and many other places. She was by no means a novice.

Kazemi was taken into custody on June 23 after she refused to surrender her equipment to the authorities. She had a permit to work as a photojournalist in the country while she waited for her visa to Turkmenistan.

According to official Iranian reports, within 72 hours, her unconscious body was transferred to Baghiatolah military hospital.

“There haven’t been any developments, other than, thank God, he is alive, and Hamid’s sister has been able to see him, but we’re still in the situation where we don’t know where this is going to go...Canada has cut diplomatic ties – they don’t have a position to connect with the Iranian authorities, so it is left up to us

By July 10, without notifying her family, authorities unplugged the life support machine. Despite statements of indignation, the Canadian government had been unable to secure any kind of protection for her.

Even though her son, Stephan, had been assured that his mother’s body will be repatriated, armed agents forced his grandmother, Ezat Kazemi, to sign a document allowing the Iranian government to bury his mother in Iran.

On July 23, Ziba Kazemi was placed in the ground, and the Canadian government recalled its ambassador.

An official Iranian government report admitted that Kazemi was beaten, but the matter was treated as in internal issue – an interrogation that got out of hand.

Iranian citizens are subject to this sort of treatment as a matter of course. But, at least theoretically, a foreign government ought not be allowed to intervene on behalf of those who have only Iranian citizenship.

But with Iran, most of Western governments seem to have thrown in the towel, even when it comes to their own citizens.

What cases such as Kazemi’s show is the starkness of diplomatic failings, and why, despite differences, Western governments need to remain engaged with Iran in a way that transcends sanctions and the game of political tit-for-tat.

Her French-born son, 35-year-old Stephan Kazemi, an artist, has spent a decade keeping his mother’s story alive, through a foundation set up in her name, through sharing her work, and, most urgently, through trying get justice for his mother – to see her killers tried in a Canadian court, to bring her body home, to get answers.

Kazemi’s exhausting battle reveals what fades with society’s short attention span, because for a son to see the list of injuries suffered by his mother in such horrifically cold, clinical fashion is to be haunted for life.

The effects of the decade-long fight show in Kazemi’s voice, with each question he asks landing like the punch of a boxer in his 12th round; still, each blow demanding an answer: Why did his mother get picked up when she wasn’t doing anything wrong, why did the Canadian government refuse to share the e-mails from her accounts with him, why the country that has been his home since his teenage years has failed so miserably in holding the his mother’s torturers and killers accountable.

“They had all these meetings in the beginning with the Iranians…but what happened? What was said? We had none of these communications, nothing tangible,” the Montreal resident told Al Jazeera.

“There was nothing saying, ‘We’re pressing Iran,” said Kazemi, adding that he felt the Canadian government was wilfully blind and therefore complicit (“if only strictly passively”) in what happened to his mother.

In a letter addressed to Canadian Prime Minister Stephen, Kazemi wrote, “I would like to ask you: What was my mother’s citizenship worth if those responsible for her death cannot be called to account for their actions before a Canadian court?”

This is a painful question for Kazemi to ask. Canada is his home. But even though he appreciates the liberties Canadians enjoy and speaks fondly of Canada for not having the same sort of track record of human rights violations as Iran, he still waits for something he can recognise as justice.

Seeking justice

Kazemi said that he’s not seeing any indication that the Canadian government is willing to learn his mother’s fate or to alter its tactics with Iran.

“They have to have the right tone and to stand by their citizens at least,” said Kazemi.

“I think they have a great opportunity to contribute to human rights in Iran, but they didn’t with my mother.”

|

Video produced by the Canadian Centre for International Justice in on the issue of Canada allowing those who torture and jail their citizens to live there. |

Tehran’s Prosecutor General , Saeed Mortazavi, is said to have been present at the time of Ziba Kazemi’s torture.

Other agents held responsible for her death were taken to court, but the case against him is dismissed in 2004. The government, did, however, offer Stephan $18,000 in “blood money” – something he viewed as an insult.

Mortazavi, incidentally, who in 2006 was sent to Geneva as part of the Iranian delegation to the United Nations Human Rights Council, shut down dozens of reformist newspapers in Iran and recently stood trial for the deaths of three protesters who were detained during the unrest following the 2009 presidential elections in Iran.

By his lawsuit, Kazemi said he’s trying to set an important precedent. Rights advocates agree – the Supreme Court hearing is scheduled for December 4, and at some point after that, Kazemi will know if he can sue the Iranian government or the individuals linked to her murder.

“We believe there is a good chance for Stephan to succeed,” said Jayne Stoyles, the executive director of the Canadian Centre for International Justice based in Ottawa.

“The key barrier at this stage in Stephan’s efforts to seek justice for the torture and death of his mother is Canada’s State Immunity Act. We believe lawmakers will be able to see that it is time to add an exception for torture that will bring the Act in to compliance with international and Canadian law, and that will run parallel to other exceptions already in the Act,” said Stoyles.

“The purpose of Canada’s State Immunity Act is to allow foreign government officials to carry out their official duties without fear of lawsuits, yet as it currently reads, the legislation also protects a government and its officials from lawsuits even when they torture and kill a Canadian. It contains some exceptions, for example it allows lawsuits against a foreign government in relation to commercial activities, but does not explicitly include an exception for acts of torture and other serious international crimes.”

Such cases, added Stoyles, will only work if there is a “strong web of accountability” that will “deter future atrocities”.

Diplomatic no-man’s land

Preventing or deterring arrests via legal means seems like the only remedy, because once one is detained, in the absence of any diplomatic rapprochement, freedom can become a cruelly elusive thing, given that the relationship between the two countries has worsened.

Canada recently closed its embassy in Iran and Iran reciprocated by shuttering its embassy in Ottawa.

With ties between Canada and Iran at their weakest point, what sort of negotiating power does Canada have when it comes to freeing its citizens from Iranian prisons? After all, as the Globe and Mail put it in a 2012 piece, “The two countries barely talk.”

This leaves the fates of Saeed Malekpour, Hossein Derakhshan and Hamid Ghassemi-Shall in a dark, uncertain place, and as their time behind bars draws on, even media attention on their cases begins to fade.

Derakhshan is serving a 19.5-year prison sentence in Evin, but was held for roughly two years, without charge, before that.

Malekpour, a metallurgic engineer with a degree from Sharif University of Technology – Iran’s equivalent of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in terms of quality and prestige – moved to Canada with his wife in long with his wife in 2004. There, he started a career as a software developer.

In 2008, while he was visiting his ailing father, Malekpour was arrested because a piece of photo-sharing software he’d created had been used in uploading pornography online. He spent a year in solitary confinement, confessed under torture – something he tried to retract in a letterfrom prison, in which he described his arrest as “an abduction” and said he was beaten and forced to sign documents he was not allowed to read.

Statistically, the regime starts to execute in high numbers leading up the elections, so we’re scared that they’re going to make a very bad decision

Malekpour was sentenced to death in 2010 for “insulting the sanctity of Islam”.

The Canadian government issued statements of condemnation, but couldn’t seem to do anything about it.

In December 2012, Malekpour’s lawyer announced that the death sentence had been suspended because Malekpour had repented for his behaviour.

Hamid Ghassemi-Shall, a shoe salesman who was also arrested in late 2009 and accused of being an agent for the Mujahedeen e-Khalag (MEK), a militant opposition group.

Ghassemi-Shall had been there since 2008 to visit his mother, who was unwell. His brother, Alborz, who was also arrested and not a Canadian citizen, died in prison. Iranian authorities said he had stomach cancer.

He was sentence to death in 2010, but like Malekpour, his sentence was commuted to life, although in 2012, he was once again put on death row.

His wife, Anontella Mega, has been relentlessly lobbying for his release.

“There haven’t been any developments, other than, thank God, he is alive, and Hamid’s sister has been able to see him, but we’re still in the situation where we don’t know where this is going to go,” said Mega.

“We know that Hamid is innocent, so for us, we know what the right answer is – he has to come home, and we remain hopeful.”

Ghassemi-Shall’s sister is in contact with Iranian authorities and that’s the only means Mega has being kept informed on her husband’s state.

“That is in essence, how it evolved. Canada has cut diplomatic ties – they don’t have a position to connect with the Iranian authorities, so it is left up to us,” said Mega.

Harper has threatened Iran with “consequences” in the event of Ghassemi-Shall’s execution, but what those consequences are remains unknown.

A request for an interview with Foreign Minister John Baird’s office was declined – Baird was on a recent tour of the Middle East, and Al Jazeera wanted to know if the subject of other Canadian-Iranians imprisoned in Iran was discussed on any diplomatic level with any possible third-party intermediary .

We also wanted a response to Kazemi’s efforts from the government. Our questions were forwarded through to the office of Minister of Consular Affairs, Diane Ablonczy, but her office too was unable to respond to Al Jazeera’s specific questions.

Ablonczy’s director of communications, however, sent us a statement on the subject:

Canadian officials have made numerous representations through a variety of channels on these cases. We continue to press Iranian authorities for due process and fair treatment.

We continue to strongly urge Iran to fully respect all of its human rights obligations, both in law and in practice.

Due to the privacy considerations, no further information can be disclosed at this time.

Baird might not have publicly discussed the fate of Canadian citizens and residents in Iranian jails. He did, however, openly discuss Iran’s meddling in the region with Bahrain and Qatar.

Hamstrung by bureaucracy

In 2009, Iranian-Canadian journalist Maziar Bahari, reporting for US news magazine Newsweek, was dragged out of his mother’s home and charged with espionage.

He was kept for 118 days and documented not only his story, but that of his family’s history with the Iranian justice system in “Then they Came for Me: A Family’s Story of Love, Captivity and Survival”.

On the extent of the involvement of the Canadian government, Bahari wrote that his editor had allowed the Canadian to take the diplomatic lead on the efforts to secure his release; however:

“But the Canadian government, being the Canadian government, was not aggressive and persistent in its approach as [Bahari’s editor] and the others would have liked.

When it comes to human-rights abuses, the Canadian government as always taken the lead in condemning the Iranian government, but its officials use bureaucratic tactics and follow very strict protocols,” wrote Bahari.

In his book, he credits media attention, social media campaigns as the probably reason for his release.

Well, that and a $300,000 bail and a promise to spy on his fellow Iranians – a common request from the Iranian government, one as standard as a confession, which Bahari also gave, on camera, in a court room as well as on Iran’s Press TV.

He was sentenced to thirteen and a half years imprisonment plus 74 lashes in absentia.

Looking for reason in a cipher

Rights advocates say it’s tough to determine why someone such as Bahari was released while others remain locked up.

Maryam Nayeb Yazdi, rights activist and editor in chief of Persian2Egnlish.com, a blog that covers Iran’s human rights violations, said that “the Canadian Government has made a perfect effort for these citizens.”

“I don’t believe that, and I have a lot of criticisms toward the Canadian government for their lack of action,” she added.

Nayeb Yazdi said that the Canadian government essentially didn’t take any action until activists such as herself stepped into the scene, for Saeed Malekpour at least, and pressured them to take action.

“Also, when the Iranian embassy was open, at least there was a place to direct queries,” she said. But no more.

“We haven’t just tried international efforts – in order to save a life in Iran, you have to also do some lobbying from inside the regime,” she said.

So expat activists try to engage clerics, activists and lawyers within Iran to try to save Malekpour’s life.

“Statistically, the regime starts to execute in high numbers leading up the elections, so we’re scared that they’re going to make a very bad decision,” she said, referring to the presidential elections marked for June 14.

That Malekpour’s death sentence was suspended was “due to international pressure, it has nothing to do with diplomatic relations,” given that there are none.

Nayeb Yazdi said that there is no official document stating that Malekpour’s death sentence has been suspended and that he therefore remains in “imminent danger of execution.”

“We know, for instance, that the US has no diplomatic relations with Iran, not even an embassy, and they were successful in freeing the American hikers,” said Nayeb Yazdi, pointing out that it was ultimately bail that secured the freedom of Sarah Shourd, Josh Fattal and Shane Bauer.

In fact, a professor of Iranian electrical engineer, held on suspicion that he planned to purchase verboten laboratory equipment in the US for over a year was freed on Saturday.

Reuters reported that Mojtaba Atarodi, 55, was released after Oman stepped in and helped Iran negotiate his release. Atarodi claims he was only purchasing basic equipment for his university lab.

But so far, there has been no successful effort for Malekpour, Derakhshan and Ghassemi-Shall, all three of whom were arrested at around the same time.

|

| Iranian blogger Hossein Derakhshan sentenced to 19.5 years for collaboration and propaganda. [Unspecified] |

But Ghassemi-Shall’s wife said that she is unaware if her husband’s case is ever raised in diplomatic dialogues with third-party states such as Turkey, which could, perhaps, help negotiate Ghassemi-Shall’s release.

While Malekpour was in no way politically active, he was a programmer and had an online presence, as was Derakhshan, who was a prominent blogger knows as Iran’s “Blogfather” for his pioneering efforts in setting up Farsi-language blogs.

“The Iranian regime, at the point in 2008, had just established its cyber army – they really wanted to crackdown on the Internet and really limit people’s activity, so they really wanted to inflict a certain level of fear,” said Nayeb Yazdi.

“I believe that this is why they’re keeping [Derakhshan and Malekpour] as leverage. Maybe their goal has changed in terms of keeping them to have negotiating power with Canada, since Canada is taking a tougher stance on the human rights situation and they are the co-sponsor of the resolution on the human rights situation in Iran,” she said.

“We plead with them [Canadian authorities] and ask them to do all they can, but those specific things, no idea if they do or in what context,” said Mega.

Still, totally isolating and alienating the Iranian government will surely be fruitless.

“Our tactic is not to boycott the Islamic Republic of Iran, because these prisoners are inside Iranian prisons, and … we have to make attempts to at least communicate with them,” she said.

At least officially, that makes activists such as Nayeb Yazdi more proactive in trying to release their fellow Canadians.

Follow @dparvaz on Twitter

This article is the second part of a series written with the generous support of the Rockefeller Foundation, and researched during a Practitioner Residency. The first part, focusing on the US, can be found here.