Britain’s northeast suffers again

Al Jazeera’s Mark Seddon looks at the historical roots of the financial crisis.

|

| About 200 unemployed men walked 450km to London in the Jarrow March [GALLO/GETTY] |

The northeast of England has been traditionally beleaguered by high rates of unemployment.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, tens of thousands of men in the area were thrown onto what was known as the ‘Dole’, or public assistance.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhy is Germany maintaining economic ties with China?

Behind India’s Manipur conflict: A tale of drugs, armed groups and politics

China’s economy beats expectations, growing 5.3 percent in first quarter

Desperation in the shipbuilding towns of Jarrow and Sunderland gave rise to what became known as the ‘hunger marches’.

In the Jarrow March of 1936, 200 unemployed men marched 450km all of the way down the country from north to south, to protest their case outside parliament in London.

Years later I met one of those marchers, a sprightly 73-year-old, who had completed much of the same march all over again from the northeast.

This was in 1983, and he was one of the many who had joined what became known as the ‘People’s March for Jobs’.

As he rubbed the blisters on his feet, he recalled the ‘old days’. People now aren’t as hungry as they were back then, he said, but acknowledged that life is still hard.

Union battle

| In depth |

|

|

|

In the early 1980s, a new Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher had embraced the monetarist economic theories of the Harvard Business School in the US.

Central to this was a belief that the trade unions had become too powerful, that inflation and public spending was too high and that much of British industry was un-productive and old fashioned.

Many believe that the recession of the early 1980s was deliberately engineered, and aimed at producing leaner and more efficient new industries, while using unemployment to depress labour costs.

Britain’s traditional industrial areas had seen nothing like it since the 1930s.

Up to three million people lost their jobs.

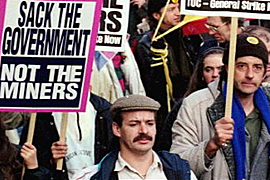

The situation was worsened by the fight-to-the-death row between the government and the National Union of Mineworkers.

Thousands more lost their jobs when the union lost that battle.

The coal industry eventually contracted and then finally expired.

Another short, sharp recession hit the area in the early 1990s, as Britain’s early attempts to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism ended in ignominious withdrawal.

The northeast, slow to recover from the 1980s meltdown, took yet another hit.

High hopes

|

| Striking English coal miners protest mine closures [AP] |

There are currently two million unemployed people in Britain; some predictions are forecasting rates as high as four million by the end of next year.

In the northeast, jobs are being lost four times faster than they are in London.

I met a young, highly-skilled car worker, who had recently been laid off from his job at the Nissan car factory in Sunderland.

Nissan, a Japanese company, is one of the new industries that replaced the old ones of coal and shipbuilding.

He had high hopes of being re-employed but was pretty realistic about what was on offer in the ‘New Brave World’ of shopping malls and fast food outlets.

Britain is likely to be the hardest hit of any of the European economies, and is in a recession that has neither been the making of the government (the result of overmanning in inefficient industries) or high inflation.

Successive governments may have been negligent, but a combination of factors have made this economic crisis particularly serious for Britain.

They include de-industrialisation, easy credit, not enough regulation of the banks and finance houses, lax labour laws in Europe and an over-dependence on the financial sector.

Self-inflicted recession

The same factors are at work in the US, but the economy there remains more diverse and better-insulated.

|

| Sarkozy recently said ‘the British got rid of their industry twenty five years ago’ [AFP] |

The rest of Europe is feeling the strain too, with sharp rises in unemployment in countries such as Spain and Poland – but for often different reasons.

Spain is part of the euro zone, and is unable to manipulate interest rates to affect demand and jobs.

Poland is a weak economy outside of the euro zone.

Germany, France and Italy may weather the storm more easily than Britain.

Frequently dismissed for having “sclerotic” or inflexible economies by some critics, the French in particular take a wry view of the Anglo-American model that they were criticised for not adopting.

Nicolas Sarkozy, the French president, recently rubbed it in with Gordon Brown, the British prime minister, saying that “the British got rid of their industry 25 years ago”.

Back in the 1970s and 1980s in Britain, the trade union bosses were blamed for many of the country’s economic woes.

Today, few even know the names of the union bosses, even in the northeast where the unions used to be strong.

They do, however, know the names of the senior bankers, whose greed and attachment to easy, if frequently complicated credit, got first the US and then the UK into a recessionary spiral.

This recession is entirely self-inflicted, but in a globalised economy, no-one can escape its effects.