Losing the Jews of Arabia

In Arab countries, “Jewish” became synonymous with “Zionist” and later, the “enemy”.

|

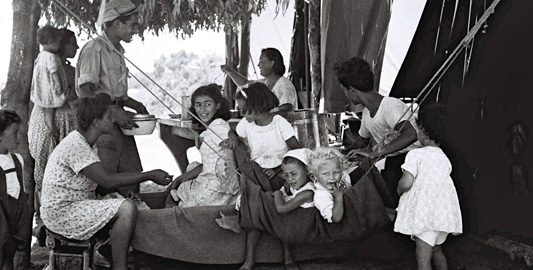

| A Jewish family outside their tent at the new immigrants’ camp at Beit Lid in the newly-established State of Israel [GALLO/GETTY] |

“The war between Israelis and the Arabs made it impossible for them to stay,” says the Israeli historian, Tom Segev of the almost one million Jews who had lived in Arab countries for several millennia prior to 1948.

Jewish populations, who once were a significant and largely harmonious minority presence in countries such as Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Iran, migrated en masse following the establishment of Israel in 1948.

In 1949-50, 49,000 Jews from Yemen were flown to Israel; in 1951, 120,000 Iraqi Jews did the same; by 1967, around 200,000 Jews had left Morocco – although not all of them to Israel.

Why did they go? Some argue that the Zionist movement, at the time predominantly European, recruited those Jews to the cause of settling Israel and setting up underground movements in Arab countries with that purpose in mind.

‘Pushed’ or ‘pulled’?

Many Israelis who came from countries such as Morocco or Iraq remember being promised better lives, large homes and plenty of work upon arrival to the new Jewish state.

Others place the impetus in religious terrain, explaining that strongly pious Jewish communities saw a messianic calling in the creation of Israel. Talk to some Israelis of Moroccan or Yemeni origin and they might say that they knew nothing about Zionism back then, just that they loved Jerusalem.

|

| A guard tower overlooks a camp for new immigrants to Israel [GALLO/GETTY] |

A different narrative suggests that rather than being “pulled” to Israel, these Jewish communities were instead “pushed” out of their home countries in the Arab world.

Even prior to the war in 1948, the increasing tensions between Palestinians and Jewish settlers to the territory were having an adverse effect on Jewish citizens of the Arab world.

That manifested either in assaults at street level or in government-sanctioned discrimination: curtailment of rights, loss of employment, stopped access to state education.

These measures were not necessarily anti-Jewish in intent, but that was their effect.

Deflection device?

In Iraq, a series of emergency measures introduced during the 1948 war were presented as anti-Zionist laws but were defined in such a way as to enable their abuse: Jews were often rounded up as suspected Zionists, as a means of extortion.

Significant numbers of Jews in such countries were not Zionists, but rather members of the Communist or nationalist movements, joining the struggle against the colonial rule that dominated the Middle East at that time.

It can be argued that, seeking a way to cope with rising and regular nationalist protests against pro-colonial governments, those regimes used their Jewish subjects as a deflection device.

Caught in the turbulent waters of conflicting currents, the Jews of Arab countries suffered the practical consequences of a conflation of terms: “Jewish” became synonymous with “Zionist” and the latter synonymous with “enemy”.

The historian Segev says: “They were not a part of that war, but as Jews they were automatically made part of Zionist aspirations, even if [those aspirations] were not necessarily theirs.”

There are myriad individual narratives of migration from Arab countries to Israel, but the collective history of this exodus has now been hijacked by agendas of each side, Arab and Israeli.

Historian Yehuda Halevi has written: “Only two contradictory tales are admitted to this mythology: the anti-Zionist myth of the perfect integration of all Jews in all Arab societies at all times, and the Zionist myth of the permanent persecution of Jews under Islam.”

The truth about the Jewish exodus from the Middle East almost certainly lies somewhere in between.

But in the ever-polarised conflict between Arab and Jew, it has become practically impossible to hold this middle ground.