‘Condemned to civil war’

Prayer for peace that underlay Afghan jirga likely to go unanswered, says Robert Grenier.

|

| About 1,600 government selected participants attended the peace jirga [EPA] |

There is a wonderful scene in a 1982 movie called The Verdict. In it, the protagonist, a lawyer played by Paul Newman, makes his final, powerful summation before a jury.

His situation seems hopeless. He knows that if the jury follows its instructions from the judge, his client will lose, and a grave injustice will go unpunished.

And so, in a thinly-veiled effort to convince the jury to ignore the judge and follow their instincts, Newman tells them that the trial they have witnessed, like all trials, is at best a clumsy and imperfect means of producing a fair outcome.

He invites them to look beyond the flawed structures of courts and judges, and instead to follow the simple, fundamental human desire which lies at the base of any system of law: The hope, indeed the prayer, for justice.

A ‘useless exercise’?

| IN depth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I was reminded of this scene as I read accounts of the just concluded Afghan peace conference, locally called the jirga.

In many ways, this conference was a reflection in miniature of the fundamental flaws of the present Afghan government: Though perhaps broadly representative, its roughly 1,600 participants were selected by the regime.

They did not include any genuine representatives of the insurgent groups to whom they were supposed to appeal.

Indeed, the gathering was denounced and physically attacked by the Taliban, and branded a “useless exercise” by the insurgent Hizb-i-Islami.

To the casual observer, the peace jirga might have seemed a genuinely consultative search for a means of achieving peace with the insurgents.

Some 28 committees were established to make proposals, which they then submitted to the chairman, Burhanuddin Rabani.

The results of those deliberations seemed strikingly familiar, however, and broadly reflective of policies touted by Hamid Karzai, the Afghan president, for some time: Guarantees of amnesty and safety, as well as job-related incentives for former Taliban foot-soldiers willing to lay down their arms; the release of insurgents held in US and Afghan prisons, presumably to accept the same deal offered to their former Taliban comrades; the removal of certain Taliban leaders from the UN blacklist and arrangements for their “asylum” in a Muslim country where peace negotiations could be held.

At the same time, at least some delegates lobbied strongly against sacrificing recent gains in democracy and women’s rights as part of any appeal to the Taliban.

Indeed, many of the jirga participants had the distinct impression that the conclusions reached by the gathering had in fact been fore-ordained.

Disregarding democracy

Regardless of the results of the peace jirga or how they were arrived at, however, it seems unlikely that its decisions will lead to peace anytime soon.

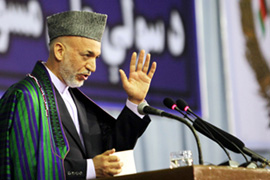

“Now the path is clear, the path that has been shown and chosen by you, we will go on that step-by-step and this path will, inshallah, take us to our destination,” intoned Karzai to the delegates as they prepared to depart.

Reconciliation cannot be imposed unilaterally, however, and an uncomfortable fact remains: There is no partner willing to walk down the designated path with Karzai.

Their missile strikes and attempted suicide attack on the jirga site only served to underscore the Taliban’s long-standing message: The Karzai government is an illegitimate, foreign-imposed entity meant to serve foreign interests, with which the Taliban will deal only after the foreign forces supporting it have left.

If and when the departure of US, NATO and other foreign forces is achieved, however, it is hard to imagine that the Taliban would deal with a fundamentally weakened Kabul regime through negotiations: One suspects the Taliban has other, rather harsher measures in mind.

Indeed, assuming that attempts to weaken or marginalise the Taliban leadership by luring away its fighters will enjoy little more success than such efforts have in the past, it is impossible to imagine what a negotiated solution between the Kabul government and Taliban would look like, or what sort of coherent national political structure it could produce.

The clerically-dominated Taliban has never shown much regard for even traditional tribal Afghan democratic norms – to say nothing of elections.

Indeed, one of the consistent complaints against Mullah Omar back when his movement controlled most of Afghanistan was that he even ignored the deliberations of his own Shura.

Even if the Afghan constitution were modified to permit greater local autonomy in areas controlled by the Taliban, is it conceivable that the Taliban would act as another political party, willingly allowing itself to be voluntarily accepted or rejected by the people? What would determine the scope of Taliban control or influence other than force of arms?

It seems most unlikely that Mullah Omar, as commander of the faithful, would subordinate himself to any law other than God’s, as interpreted through the Taliban’s own bleak and obscurantist norms.

A ‘divided house’

|

| The outcome of the jirga reflected policies previously touted by Hamid Karzai [EPA] |

The current trajectory of events in Afghanistan is already tending toward a de-facto “soft” partition of the country.

Given the gulf between the governing norms of the Taliban and those of the Kabul regime – or of the ethnic minorities who are its most natural constituency – it is hard to see what sort of agreed common governing structure could be arrived at to establish peace and some sort of political coherency in the country.

It is similarly hard to see how and why the Taliban, after all it is a national and not an internationalist movement, would deny safe haven to al-Qaeda and other foreign militants, especially given the important support they have provided against what many see as foreign occupying forces.

Without a clear and verifiable break between the Taliban and al-Qaeda, however, it is unlikely that the US will entirely abandon the field in Afghanistan and acquiesce in the al-Qaeda haven which motivated its armed intervention in the first place.

Abraham Lincoln once said that “a house divided against itself cannot stand”. The US had to fight a bitter civil war to overcome the profound internal divisions to which he referred.

Likewise, the peace jirga notwithstanding, it seems that Afghanistan is condemned, when all is said and done, to an open-ended civil war.

The precise form that this civil war will take, and the longer-term role of foreign military forces in Afghanistan once the counter-insurgency effort in Afghanistan’s Pashtun areas has failed, both remain to be seen.

In the meantime, however, unlike in Hollywood, the hope, indeed the prayer for peace which underlay Karzai’s peace jirga, is likely to go unanswered.

Robert Grenier was the CIA’s chief of station in Islamabad, Pakistan, from 1999 to 2002. He was also the director of the CIA’s counter-terrorism centre.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.