Opposition fears in Kyrgyz election

Some analysts believe the electorate is likely to vote for incumbent leader.

|

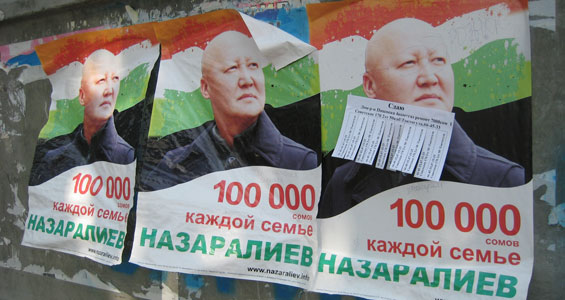

| In the battle of campaign posters, the opposition have used images of their candidates [WALKER] |

His posters are everywhere, but you won’t find him on any of them.

Instead, the campaign of Kurmanek Bakiev, the president of Kyrgyzstan, features ordinary Kyrgyz citizens, smiling down from giant billboards.

The red background and font of assorted slogans such as ‘Only Bakiev’ and ‘Bakiev Of Course’ are unmistakably reminiscent of the Soviet era, but the faces belong to contented 21st century adults.

Simultaneously progressive and conservative, Bakiev’s campaign posters offer a slick message for a diverse electorate who must choose their president on July 23.

The billboards of Bakiev’s opponents are less numerous and none of them have the financial clout behind his campaign.

They include Jenishbek Nazaraliyev, a bald-headed celebrity doctor noted for his pledge to change the national flag and to introduce legalised opium farms.

Another candidate, Nurlan Motuyev, is a charismatic business entrepreneur who caused a scandal after allegedly illegally helping himself to a coal mine.

Main contender

The main opposition contender is Almazbek Atambayev, a former prime minister in Bakiev’s cabinet, who is now the front-man for the United People’s Movement (UPM), a loose coalition of opposition parties.

Atambayev’s team have devised youthful but modest graffiti-themed posters and the occasional spray-painted mural with the Obama-esque slogan ‘Together we can’.

The UPM, he says, simply wants to restore power that has been hijacked by a criminal elite.

“This is the main point of our programme. We don’t want the whole country to work for one family and its surroundings. We want the opposite: Authority to work for the people. The President must not think of himself as a khan or sultan”.

Analysts say that despite the UPM’s corruption-busting manifesto and proposals to limit presidential powers, it lacks a unified front.

The strategy was to put forward a single challenger, but then another UPM leader, Temir Sariev, broke from the arrangement and decided he would also run.

Political scientist Marat Kazakpayev says voters are confused by the choice and by Atambayev’s former association with the administration.

“He was in power, he was in business. Now again, he’s in opposition and most people simply do not believe in him.”

Opposition fears

|

| Bakiev’s posters feature images of Kyrgyz citizens [Walker] |

Critics accuse Bakiev’s government of increasingly repressive tendencies that include a crackdown on religious minorities, restrictions on the right to assembly and on the formation of political parties.

In June, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) called on the Kyrgyz authorities to prevent attacks on journalists.

In one assault in March, a political analyst was beaten and stabbed 29 times by unknown assailants. This month a journalist died after surgery for injuries he sustained in an alleged police beating.

Then there was the death of Medet Sadyrkulov, a former head of the presidential administration who was switching allegiances before he was killed in a car accident.

Opposition figures have whispered that it was an assassination. While such claims are unsubstantiated their fear is genuine.

Many of them have been tried on criminal charges. Some have been imprisoned.

But Tabyldy Orozaliyev, the director of Bakiev’s election campaign, proudly points out that compared to its neighbours, Kyrgyzstan is an island of democracy and free speech.

“Go and look at other countries in this region,” he says.

“Go out and read the newspapers in the kiosks and see how people are free to write about the president and parliament. You can’t silence people in our country.”

Kyrgyzstan is chronically poor, and many of its elderly receive less than a dollar a day on state pensions. Towns and cities across the country suffer frequent blackouts.

Orozaliyev, however, points to the numbers of schools that have opened under Bakiev’s rule, and the boosts to industry such as the opening of cement and chemical plants.

Post-revolution blues

In 2005, angry crowds forced an unpopular former president, Askar Akayev, from office in the colour ‘Tulip Revolution’.

Bakiev came to power in a subsequent election that was grudgingly approved by the OSCE.

But the optimism that Kyrgyzstan might emerge as a lighthouse in a Central Asian sea of autocracy has since dried up.

Public mistrust turned into unrest, as international monitors concluded that subsequent national polls were falsified, especially parliamentary elections in 2007 which delivered all but a handful of seats to the ruling party.

Many observers, both foreign and Kyrgyz, believe the winner of this poll has already been decided. The National Democratic Institute, the US-based NGO, has publicly voiced its concerns that the presidential election of 2009 may not be credible.

On the streets of Bishkek, the capital, many people told Al Jazeera they would back their president, a reflection of the suspicion among analysts that he needs no vote rigging to comfortably win a second term.

Ultimately the public wants stability, says Marat Kazakpayev.

“People are tired of mass demonstrations. Moreover there is apathy. People have lost trust in the opposition and in authority. So the electorate could side with the president”.

Brokering deals

Some of that stability has emerged from Bakiev’s foreign policy. He has secured deals with the major powers seeking influence in the region, such as infrastructure development from the Chinese.

The Russians have promised almost $2bn in loans to develop Kyrgyzstan’s hydroelectric capability and have delivered a $300m grant.

And the president managed to significantly raise the annual rent on Manas, the US airbase that is a critical supply and troop hub for the war in Afghanistan.

Some observers express concern that the new deal with Manas may prompt countries like the US to be muted in their criticism of the current political climate in Kyrgyzstan.

In a recent Dow Jones article, Baktybek Abdrisaev, the former Kyrgyz ambassador to the US, urged Washington to maintain a principled attitude to the regime and to continue to encourage political reform.

Elvira Sarieva, a media consultant, says there are signs even international NGOs may be losing enthusiasm for an election whose outcome seems to many a foregone conclusion.

Kyrgyzstan’s Media Commissioner Institute, an NGO group assessing bias in the state media, initially struggled to gain foreign sponsorship.

“That’s a worrying sign because that pessimism spreads from the foreign organisations and will ultimately influence the mood of local NGOs. Consequently their activities decrease,” Sarieva said.

“Young activists become disillusioned, and that only makes the situation worse. Nobody should give up trying to make a difference.”