Cambridge University Library unveils historic treasures

Library celebrates 600th birthday by putting rare manuscripts, books, tools, bones and drawings on public display.

Cambridge, UK – It’s hard to believe this long, dark basement room at Cambridge University Library holds thousands of years of heady thought from religion to physics, anatomy to evolution.

Peer through the dimness, into the glass cases and you’ll see some rare treasures from the library’s collection of eight million items.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

To mark its 600th birthday manuscripts, books, tools, bones and drawings are coming out from the cold, light-controlled storage rooms so the public can have a look.

Librarian Emily Dourish put together “Lines of Thought: Discoveries that Changed the World” which opens on Friday and runs until September 20.

She wants visitors to leave inspired just as the scientists, writers and deep thinkers on show were inspired by the thoughts that came before them.

Her favourite object? The Gutenberg Bible, the first Western European book – 1455 – to be printed using movable type.

“It set off a printing revolution in the West that changed everything. It meant that books were no longer just for people living in monastic orders or the wealthy. It meant that ideas could spread around Europe.” Dourish explained.

“The paper was made from squashed-up rags that were formed into a papier mache consistency,” Dourish said, lifting a page to show the thick, stiff paper. “It lasts much longer than paper made from wood pulp which is more acidic.”

With so many rare books and manuscripts it’s impossible for the Cambridge librarians to know everything. They are constantly learning from scholars and academics who visit to study the works.

Paul Needham, an expert based at Princeton University, in the US, explained to Dourish that the markings on the bible’s margins – what we now call hashtags – would have been used to help the printer remember where to stop and start.

![The Gutenberg Bible was the first Western European book [Cambridge University Library]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/7f7207a0a11c441cafafec6099352177_18.jpeg)

Around 180 bibles were produced in Mainz in 1454-55 by Johannes Gutenberg. Only about 15 remain.

The bible is written in Latin with two even rows on each page. The illuminations – drawings and coloured letters – were drawn by hand after the bible had been printed.

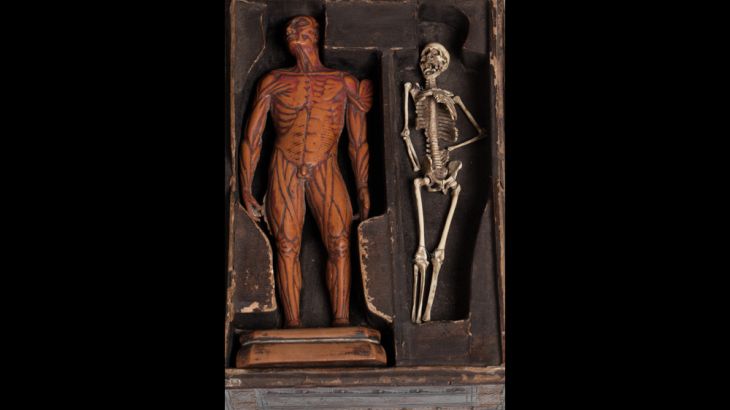

The exhibition’s medical section, “Illustrating Anatomy”, is particularly fascinating.

Anna Jones, Whipple Librarian at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, talked me through the case which holds a box of frightening tools used for dissection in the 19th century and a book about anatomy given to the library by Thomas Lorkyn (1528-1591), a professor of physics, who carried out the first human dissection in England in 1565.

“The body was that of a criminal who had been hanged. They had to work quickly because there was no way to preserve the body,” Jones said. “Can you imagine the smell?”

Some of the pages in the thick, leather-bound book are stained which makes Jones think it was heavily used in dissection theatres; part of Cambridge’s medical the training required doctors to attend two dissections.

![One of the treasures from the medical section [Cambridge University Library]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/351ecafe6dd7483bb306c0bcd2b6bb3a_18.jpeg)

The boxwood figure next to an ivory skeleton were given to the library in 1591 by a leading London surgeon. They would have been used by medical students in the 16th century. Librarian Emily Dourish noted the figure’s “poignant” expression, perhaps as a result of his skin having been peeled away.

Below, you can see what librarians refer to as “the world’s first pop-up book”.

Published in Switzerland in 1543 Andreas Vesalius’s book contained an ingenious detachable cut-out manikin to allow students to build their own human with multiple layers of organs.

!['The world's first pop-up book' [Cambridge University Library]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/7bbdf0db281e4c4f8fde3c8988e6fa66_18.jpeg)

In the section devoted to “Technical Revolutions in Communications” are some 3,000-year-old oracle bones from China. Charles Aylmer, head of the Chinese department at the library, had a 3D-printed copy of one of the bones made to better explain how the process worked.

On one side of the cow bones heat was applied, causing it to crack. The lines from the crack on the other side were then “read” – like tea leaves or a palm – by a diviner to predict the future.

“The most common question was: ‘will anything happen in the next 10 days?’ because that was the equivalent of their week,” Aylmer explained.

The diviner typically asked two questions, Aylmer said. For instance, “Shall we sacrifice an ox? Shall we not sacrifice an ox?” If the answers didn’t contradict each other then they’d take it as correct.

![Oracle bone, dating back from the Shang dynasty [Cambridge University Library]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/84539ad6adb84d4ea95acaf2de87b7e5_18.jpeg)

The oracle bones are some of the earliest written artefacts in the library and contain the oldest known records of Chinese script. They date from the Shang dynasty which ruled central China from the 16th to the 11th Century BCE.

Yasmin Faghihi is in charge of the library’s Middle Eastern department and is responsible for 4,500 rare manuscripts, including a number of works in the exhibition.

Below is the 17th century copy of the first known Islamic anatomical text to include full-body illustrations, Mansur ibn Ilyas’s 1386 Tasrih-I mansuri.

![The first known Islamic anatomical text to include full-body illustrations [Cambridge University Library]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/32e4ea84de7f4043a35ccca9d3fd4826_18.jpeg)

Faghihi took me behind the scenes to see what happens when a scholar comes to Cambridge to study a rare work.She rolls a trolley in the cold rooms filled with movable shelves and collects a 1535 treatise on Islamic ritual law, written in Spanish and a fragment of an 8th century Quran.

Once in the hushed reading room Faghihi carefully nestles the fragment and manuscript onto soft, neutral-coloured cushions filled with cotton wool. The 8th century fragment, probably from a Damascus mosque, with its brown edges and bumpy surface, sits open.

Faghihi opens the treatise and puts a cotton rope across; it’s called a ”snake” and is filled with lead weights.

”You need to keep the book open so they can be studied but with old books they shouldn’t be opened too much. The snakes help to distribute the weight evenly and there are no sharp edges,” Faghihi explained.

The 8th century fragment has been digitised so scholars can access it online. But Faghihi said there’s nothing like coming face to face with a manuscript.

”It’s real, it’s there in front of you. You can touch it. They have a smell and it makes you realise that this is history, someone wrote this,” she said.

But as not everyone can get to Cambridge, even for the sexcentenary year, the library is looking for donors to support digitisation. They’ve got the high-tech tools needed to photograph each page but it’s time-consuming and expensive for an expert librarian to research and input all the information needed to go with the images.

With 600 years of collecting – there’s plenty more to see in the show: notebooks of Charles Darwin, Isaac Newton’s annotations, written in Latin, the scholarly language at the time. You can download a free iPad app: Words That Changed the World.

And there’s much more on the Cambridge University Library website.