Case made for tsunami alert centre

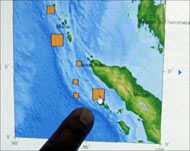

Pressure has built for an Indian Ocean tsunami warning centre after frustrated scientists said they knew killer waves were speeding towards coastlines across Asia but were powerless to raise the alarm.

The Pacific Tsunami Warning Centre and the International Tsunami Information Centre, both in Hawaii, detected the 26 December earthquake off Indonesia that generated the Indian Ocean tsunami.

But the centres were set up to provide alerts to Pacific nations, and frantic scientists had no contacts in the countries in the path of the giant waves which experts said could rush across oceans at up to 800km an hour.

As a result, they lost the chance to alert some of the worst-hit areas hours before the tsunami hit, killing more than 25,000 people in nine countries.

“There was sufficient time between the time of the quake and the time of the tsunamis hitting some of the affected areas to have saved many lives if a proper warning system had been in place,” US Geological Survey geophysicist Ken Hudnut said.

Australia has now proposed an Indian Ocean tsunami monitoring network to mirror the Honolulu-based system already covering the Pacific.

Japan said it would suggest a similar system at a disaster management conference in Kobe next month, and some Commonwealth countries said they were considering banding together to provide global tsunami warnings.

Public concern

Japan also announced it would establish a tsunami warning centre in Tokyo covering the northwestern Pacific from Siberia to Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, where 2200 people were killed by a tidal wave in 1998.

|

|

More than 25,000 people have |

Amid growing public concern about why no alarms were sounded, Thailand and Malaysia said they would ask Japan to help set up an early warning system.

Commenting on the flurry of activity, Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer said an Indian Ocean warning centre was overdue, and it was a case of “better late than never” if it saved lives.

“I know it looks a bit like closing the door after the horse has bolted but there will be tsunamis again in the future, though hopefully never again on this scale,” he said.

Geosciences Australia senior seismologist Phil Dunning, who proposed such a centre in September 2003, said even the scientific community had little appreciation of the risk.

“There wasn’t much interest among the scientific community, outside of Australia and Indonesia,” Downer added.

“The historical record of tsunamis in the Indian Ocean is not very good and there is very little data so there was very little awareness. I guess events have really caught up with us.”

First since 1883

The tsunami is believed to be the first in the Indian Ocean since 1883, associated with the famous eruption of Krakatoa between Sumatra and Java, possibly explaining why coastal inhabitants of the region were so unprepared.

|

|

Tsunamis are common in the |

“Because they are such a rare occurrence, perhaps the tradition of warning about the hazards of tsunamis is no longer handed down from generation to generation,” Hudnut said.

Tsunamis are far more common in the Pacific, which lies in the so-called Ring of Fire of geological hotspots.

Dunning said the Pacific warning system, established in 1949 after a tsunami killed 149 in Hawaii, uses seismic monitoring and tidal gauges to predict the destination and severity of tidal waves.

Public warnings are issued via coastal sirens, television and radio bulletins and even SMS messages in some countries.

Downer said there was no guarantee an Indian Ocean tsunami warning system would have saved lives, as South and Southeast Asia’s population was much larger than many Pacific nations and often lacked the communications infrastructure of industrialised Pacific nations.

However, Dunning said any warning would save lives.

“Even if you can only get an alert out 30-60 minutes before it hits, at least that gives some people a chance to get to higher ground,” he said.